Aid

Limits of sovereignty

Wong/picture alliance/AP Photo

Wong/picture alliance/AP Photo

Rather strict rules define what counts as official development assistance (ODA), the aid that established economic powers have pledged to grant developing countries. South-south cooperation is certainly of similar relevance, but as the term is vague, serious comparisons are impossible.

Some people romanticise south-south cooperation. In a South Centre publication (Research Paper 88, November 2018), for example, it was recently declared to be a “non-hierarchical expression of solidarity among equal partners”. The South Centre is a Geneva-based think tank that is owned by countries of the global south. The author considered any kind of exchange among developing countries and emerging markets to be south-south cooperation – from trade to foreign direct investments on to ODA-like infrastructure lending.

Such rhetoric is politically correct, but factually incorrect. Powerful emerging markets like China, India or Brazil cannot be equal partners of least developed countries. Governments that can grant huge loans are obviously more powerful than the clients who need those loans. Moreover, the interests of a commodity-importing manufacturing hub such as China differ from those of commodity exporters. It matters too that the relations of China with India or Brazil are tension-prone.

China is the second most powerful country on earth. Over the past decades, its government has become increasingly assertive internationally. Its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is building infrastructure in many Asian, African and European countries, financing roads, harbours, power stations et cetera. Beijing is involved in related projects in Latin America as well.

All countries concerned need more and better infrastructure. Nonetheless, China’s engagement is not beyond criticism. It lacks transparency, for example, so the public has no clear idea of the financial liabilities. Some projects fail, and governments then struggle to repay loans that proved worthless.

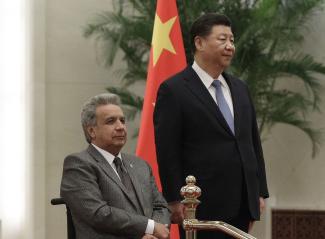

Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Ecuador are three countries, where current governments are struggling to service the debts that their predecessors have piled up. The previous leaders, moreover, are controversial, to put it mildly. Charges of corruption and inappropriate governance abound.

Examples like this illustrate the limits of sovereignty. In principle, Beijing claims not to be interfering in other countries’ domestic affairs. In practice, Chinese loans pre-define what scope for action partner governments will have in the future. If projects go well, that scope will increase, but if they fail, it becomes severely restricted. Even if Beijing forgives some of the money, as it occasionally does, problems persist. In Sri Lanka, for example, it took control – for an entire century – of a port it built in exchange for debt relief worth about $ 1 billion. That was a deal Sri Lanka’s government could not reject.

It is short-sighted to praise China for not tying aid to conditions as established powers do. Unfortunately, the action of a formally sovereign government is not by definition legitimate. Corrupt leaders tend to incur debts, the impact of which is only felt once they are no longer in office. That is one reason why western powers started to take interest in issues of debtor governance. Too many of their own projects failed.

Conservative pundits in the USA warn that all Chinese loans basically amount to debt traps. That is overblown. China has a role to play in global affairs and should certainly contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Well considered rules for south-south cooperation would serve that purpose – and they would also serve the enlightened self-interest of China and other rising powers. Indeed, Beijing has shown interest in cooperating more closely with western donor governments on debt sustainability, reconsidering its own approach to aid. In view of huge challenges, the international community needs sober assessments and cooperation that delivers results. The summit in Buenos Aires can help to make that happen.

Link

Yuefen Li, 2018: Assessment of south-south cooperation and the global narrative on the eve of BAPA+40. Geneva: South Centre.

http://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-88-november-2018/

Hans Dembowski is the editor in chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@fazit-communications.de