Health

“What other option do we have?”

Erica Mbambu (name changed) is a 31-year-old undocumented immigrant to South Africa from neighbouring Zimbabwe. She supports herself by performing sex work in the illegal brothels of Johannesburg, South Africa’s commercial capital. She is HIV positive.

For a decade, she managed her disease by taking the free antiretroviral pills that South Africa’s public clinics gave out to anyone in the country who was living with HIV – whether they were a citizen, legalised resident or undocumented foreign worker.

“For people like me, South Africa was the country where you could arrive today, get tested for free tomorrow, and start taking antiretroviral medication within a week,” she says. But this year, that system has broken down.

The largest epidemic in the world

South Africa has the largest HIV epidemic in the world. Nevertheless, the country, along with neighbouring Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Malawi, has made remarkable gains in recent years in reducing deaths and new infections. Last year, South Africa’s treatment programme – the world’s largest – supplied antiretroviral therapy (ART) to approximately 6 million of the 7.8 million South Africans who were known to have HIV. Often delivered in pill form, ART lowers the levels of the HI virus in the body and reduces the likelihood of a patient developing the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) from it.

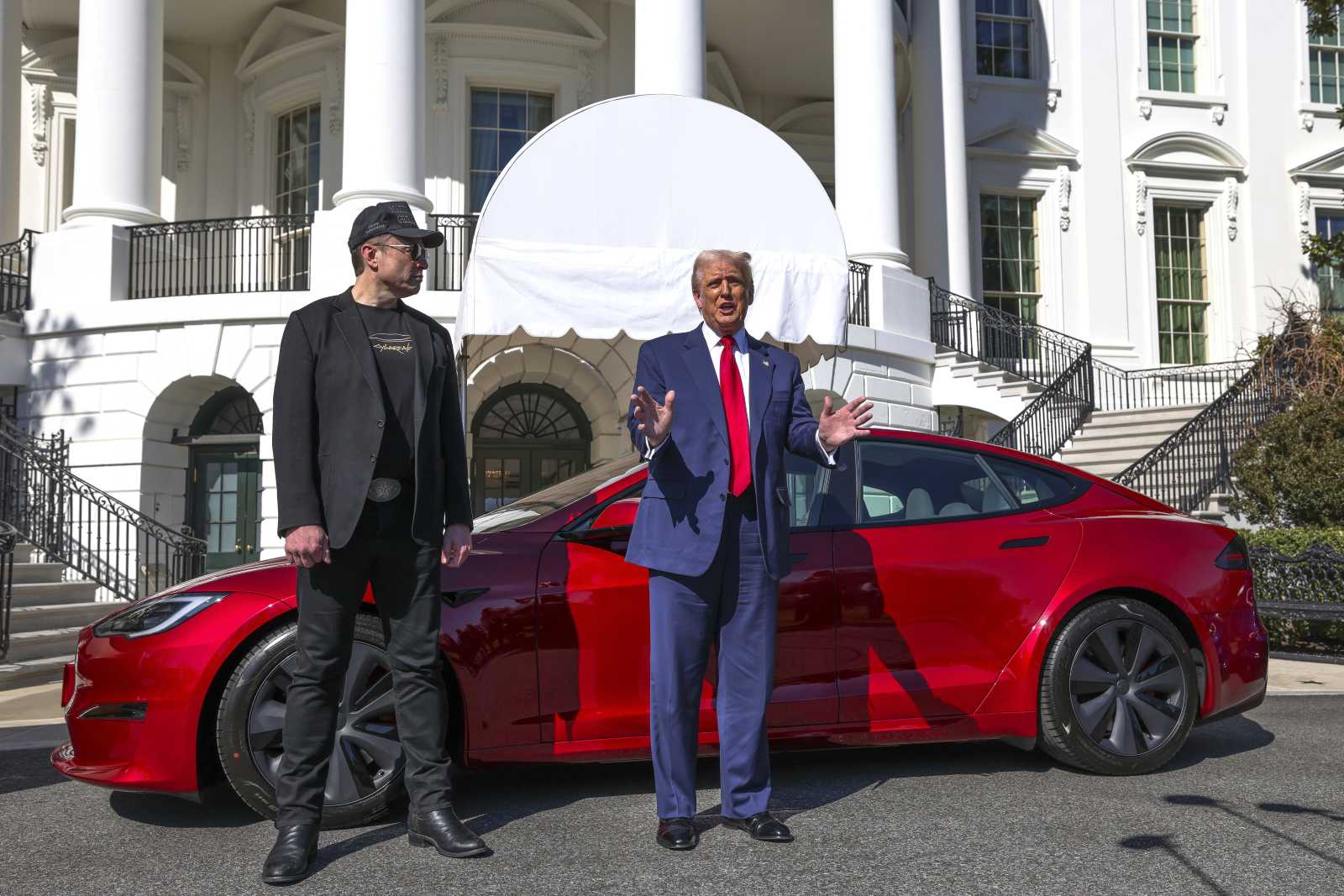

The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) programme has invested $ 8 billion in South Africa since its launch in 2003. Last year, the US contributed over $ 450 million to fight HIV in South Africa.

For two decades, South Africa’s public hospitals have been able to provide ART to people like Erica Mbambu for free. Since 2016, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which prevents HIV infections in the first place, has been available as well.

Like Mbambu, Irene Jani, a 28-year-old undocumented migrant from Malawi, performs sex work in a slum in Johannesburg. She has sex without a condom with clients who pay higher prices, but so far has been able to avoid an HIV infection thanks to a free PrEP drug funded in large part by the US government.

In January of this year, however, Donald Trump signed an executive order halting all foreign aid, including funding for PEPFAR and USAID programmes.

The results of the funding freeze have been devastating for South Africa: Over 8000 health workers have lost their jobs, clinics have closed, treatment has been disrupted, and essential research has been shut down.

Medical xenophobia

Unsurprisingly, the cuts have hit marginalised people like Erica Mbambu and Irene Jani the hardest. Discriminatory attitudes towards undocumented migrants are exacerbating the problem. “Nurses refuse us pills now,” Erica Mbambu says. “They cite Trump and say that the medications that are left are reserved for South African citizens and legalised foreign workers.” Irene Jani can also no longer obtain her prophylactic drug at the clinics she has access to.

To make matters worse, the anti-immigration group “Operation Dudula” has been blocking entrances to some public hospitals and chasing off undocumented migrants seeking all types of medical care, from pregnancy monitoring to HIV treatment to malaria diagnoses. “Operation Dudula” means “Operation Force Out” in the dominant isiZulu language.

It is not the official policy of the South African government to deny HIV treatment to undocumented foreign nationals, and “any South African blocking hospital premises to cut off patients from critical care faces arrest,” says Sandile Buthelezi, the director-general of the National Department of Health.

But the director’s reassuring words are hot air, says Tino Hwakandwe, an advocacy manager with the Zimbabwe Refugee Alliance in South Africa’s capital Pretoria. “Nurses are telling undocumented migrants to get treated in their home countries. Then they sell them HIV medication under the table,” he says.

A dangerous black market

Erica Mbambu has resorted to bribing healthcare professionals for her pills. “I pay bribes because I don’t want to die early from untreated AIDS,” she says. “My kids depend on me.”

Irene Jani, on the other hand, is buying drugs that have been smuggled across the border from Malawi, 1500 kilometres away. The pills are then sold on the street for about $ 30 for a month’s supply. “The medication is stolen from dispensaries in Malawi by public hospital nurses because healthcare workers over there are paid so little,” Jani explains. Her source is precarious, however: Malawian clinics also rely on funding from USAID.

Taking HIV drugs without medical supervision is “a dance with disaster,” says Ndiviwe Mphothulo, president of the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society. “Fake HIV drugs could sneak onto the market and amplify drug-resistant strains of syphilis, HIV or gonorrhoea. People taking these drugs without baseline liver and kidney tests are risking organ injury.”

Jani feels uneasy taking black market drugs, but she has no choice if she wants to stay HIV-free. Mbambu faces the same dilemma, asking, “What other option do we have?”

In an analysis of the impact of the PEPFAR cuts, Linda-Gail Bekker, a prominent South African HIV expert, warned along with her co-authors that the Trump administration’s decision could result in “as many as an additional 565,000 new HIV infections and 601,000 HIV-related deaths in South Africa by 2034”. The permanent loss of US funding could undo decades of progress; the current freeze is already threatening the lives of South Africa’s most vulnerable residents.

Ray Mwareya is a freelance reporter covering health matters in Africa.

raybellingcat@gmail.com