Satire and journalism

“Criticism of what rules, coated in candy”

Tim Wolff interviewed by Katharina Wilhelm Otieno

How would you define the border between satire and journalism – what is each discipline able and allowed to do? How do they influence and complement one another?

Satire, I would propose, is an art form that springs from the human need to not let the seriousness of being simply be. What is, what prevails, what rules our lives has to be questioned, laughed at and sometimes even insulted.

The fact that satire and journalism seem so similar is probably due to the fact that we – for now – perceive the world and the forces that govern it through a journalistic lens. That’s why almost all modern forms of satire resemble journalism formats, from satirical newspaper columns to “The Daily Show”. Satire is at the same time always a parody of prevailing methods of information delivery. Thus, the borders are porous and also dependent on audiences’ media literacy.

The best journalism aims to deliver every repeatedly verified detail in a serious way; satire uses comedy and criticism to question what conclusions we should draw from those details. One strives for order, the other against it.

Yet satire cannot exist without journalistic groundwork, because satire is always a reaction to something else. In that respect, satire is also structurally conservative, because everything new is initially met with scepticism, whereas journalism can respond more quickly to the latest developments. Therefore, the relationship between the two offers a good way to deal with life’s contradictions – without coming to more than preliminary conclusions. It seems to me that the only true difference between journalism and satire is that journalism, done correctly, is serious; satire, done correctly, appears serious. If you want to combine the two, there is a greater risk of misunderstanding what is serious and what is not.

How do you create a balance between entertainment and information?

With a lot of hard work. By getting close to and stepping back from my own text again and again until it no longer puts one or the other at risk.

You are not only the publisher of Titanic, but also work in various media and formats, such as ZDF Magazin Royale, a German satirical TV programme, wrote a book ("Best of Sapiens") and a TV movie ("Hallo Spencer – der Film"). How do you change your approach for different platforms, and what challenges does that create?

Satire and comedy always have to be aware of the context in which they appear. You have to know where you will be publishing. Otherwise, spoken text differs from written text only in that you have to come to terms with the person presenting it. This is true even if you are the presenter.

In the era of fake news and disinformation, how can satire promote media literacy and improve the public’s critical-thinking skills?

By staying true to its core mission: delivering criticism of what rules, coated in candy. That said, neither the criticism nor the coating always has to be high quality; clever stupidity is often the most entertaining. But that always means painstaking work: to find out what actually rules. Even if it is only the shared knowledge that prevails in the virtual or real space we play in. This is becoming more difficult in times of fake news and disinformation, but also due to the fragmentation of information dissemination through individualised news. Nowadays, many people think that satire is better than traditional journalism, because the seriousness of journalism is compromised by speed, a lack of fact-checking and (corporate) bias. But serious satirists never stop making an effort.

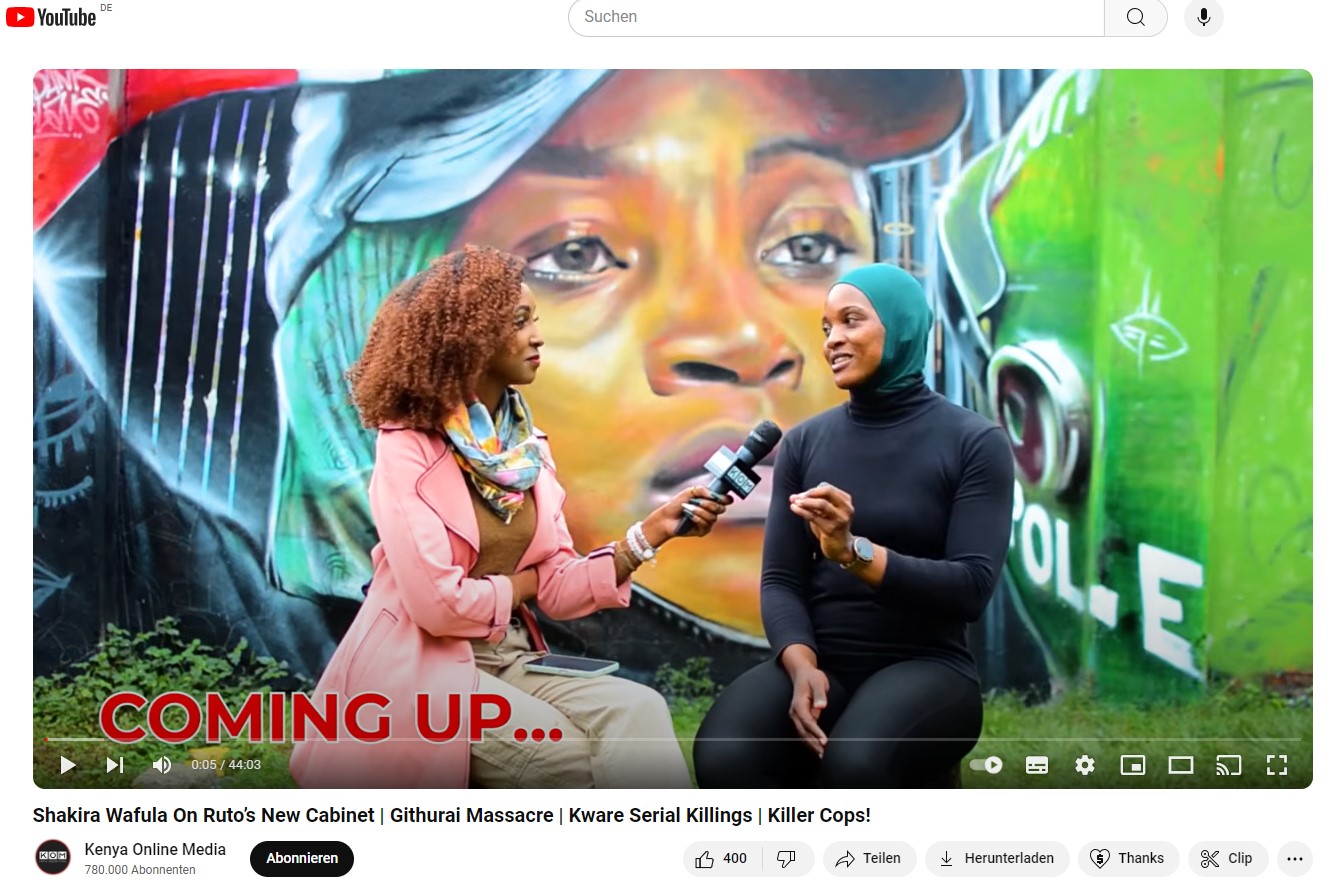

Many countries of the global south restrict the freedom of the press and of expression. What role can political satire play in those contexts?

Through satire, you can say what is happening without saying what is happening. That is undoubtedly a good way to lighten the burden of oppression. In my experience, however, satire can offer comfort but can change little more than the attitudes of just a few people. Real change is not compatible with irony, at least not fundamentally.

How do you assess the situation of freedom of the press and of expression in the western world?

In the so-called western world, satire is subject to what Critical Theory calls “repressive tolerance”: It is tolerated because it is considered proof of the freedom of expression. Moreover, it is limited to cheerful criticism that changes little or nothing but, at best, creates the illusion that the act of criticism itself has changed something.

Satire only becomes problematic – especially for itself – when it attacks the business foundation of the hand that feeds it. That’s why the American comedian Jon Stewart can’t talk about production conditions in China on AppleTV, though he can on “The Daily Show”. But I think that will change too when the capitalism that is based on fossil industries transforms into a fossil fascism – which the USA in particular is experimenting with right now.

With regard to global digital networks: How do social media influence your work, and what opportunities and dangers do you see for satirists and journalists worldwide in this context?

Social networks are places of new understanding and great misunderstandings. You can encounter different perspectives faster than you ever would have without social media – and then reflect on clichés and assumptions. This is where social networks have an enlightening effect at best. Because comedy, in particular, works with the reproduction of resentments. And when the potential audience is larger and more diverse, you have to scrutinise your methods. The danger when comedy crosses borders, however, is the cultural misunderstanding that can also end in violence, at least since the Mohammed cartoons and the attack on Charlie Hebdo. Across certain boundaries, it is not always possible to communicate what is actually meant, or could be meant, by improperly occurring comedy.

Tim Wolff is a German satirist and journalist.

euz.editor@dandc.eu