Literature

How can we infer the colour of a person’s skin?

Twyla and Roberta are eight-year-olds when they meet at St Bonny’s children’s home in the US. They are not orphans like the other children; their performance at school leaves a lot to be desired, and their mothers, both single parents, are unable to cope with them – one because she is ill, the other because she “just likes to dance all night”. So, both girls end up spending four months in a home, where they have to share a room. One of the girls is black, the other white.

“We looked like salt and pepper standing there,” says Twyla. Initially, the two girls view one another with scepticism and suspicion, influenced by their respective parental homes. “My mother [...] was right. Every now and then she would stop dancing long enough to tell me something important and one of the things she said was that they never washed their hair and they smelled funny. Roberta sure did.” But then they become confidantes, because they are the only children who have been “dumped” in the home, with no “beautiful dead parents in the sky”. They are therefore very low down in the orphanage hierarchy. In fact, there is no one below them except Maggie, the mute kitchen woman who is tormented and ridiculed by everyone and whose story runs like a red thread through the entire narrative.

After 28 days, the two girls receive a visit from their mothers – Roberta’s mother with a huge cross around her neck and a Bible under her arm, Twyla’s mother in tight green slacks and a shabby fur jacket. Twyla’s mother holds out her hand in greeting but Roberta’s mother grabs her daughter and hurries away. Did a white woman refuse to greet a black woman or did a black woman refuse to shake hands with a white cheerful soul?

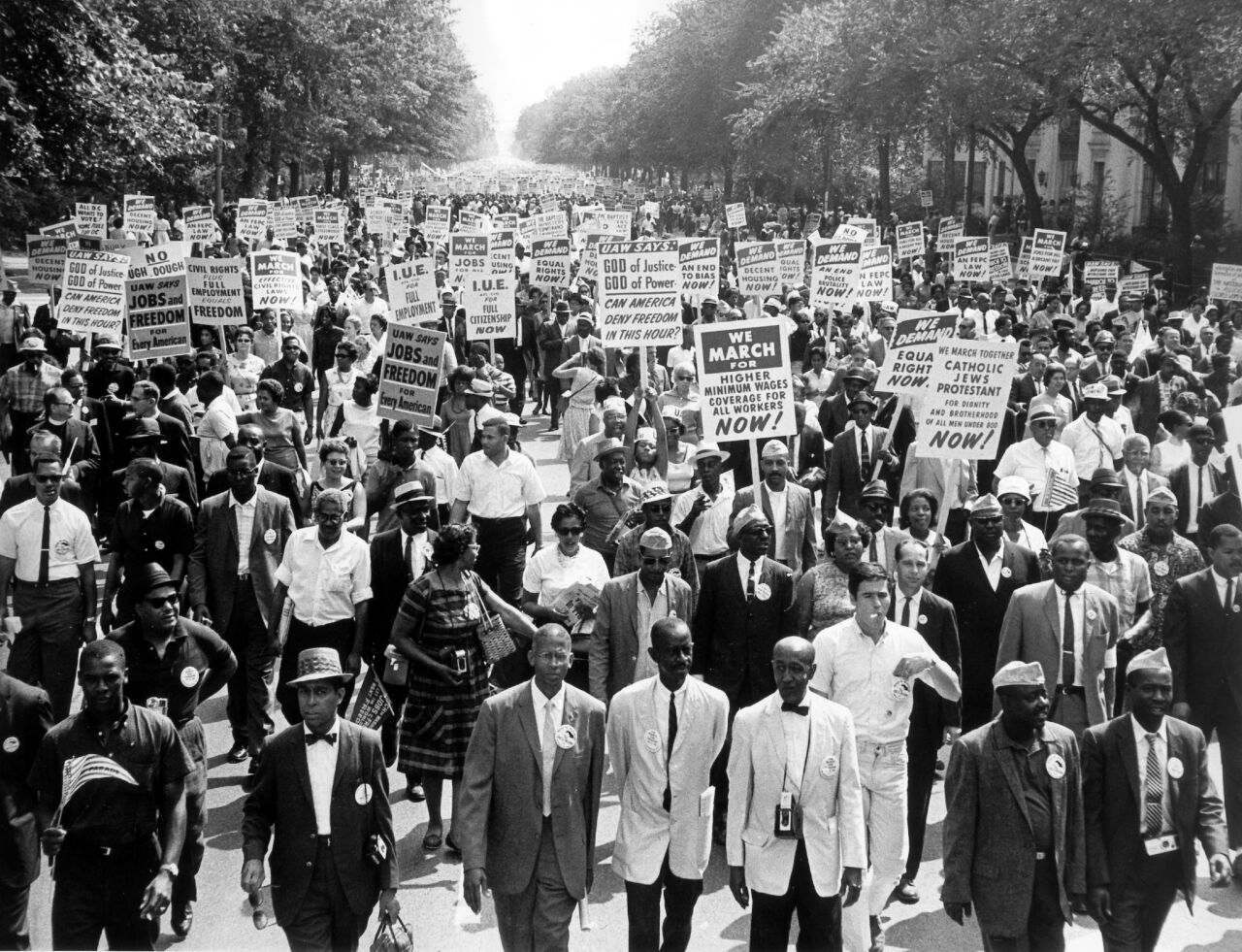

Eight years later, the two girls meet again. They still live in the same town. Twyla is now working behind the counter in a diner, wearing a uniform and thick opaque stockings. Roberta is dressed to the nines and accompanied by two young men with big hair and beards. They are on their way to see Jimi Hendrix. Time passes. The two girls, now young women, meet again in a shopping mall. Roberta has a very wealthy husband, Twyla is married to a fireman and has a son. More time passes. Roberta and Twyla meet at a demonstration. It has been decided that white and black children should go to school together. Twyla is in favour, Roberta is not.

Toni Morrison won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993, becoming the first black woman ever to receive the award. In her short story, she repeatedly plays with racist prejudice, with codes that could point to the protagonists’ racial identity. The reader is puzzled and tries to judge the colour of the characters’ skin from outward signs, tell-tale language or social status. But there are no reliable clues. What seems plausible could be completely wrong. A person who is poor and oppressed does not necessarily have to be black. A person of wealth and high social standing is not automatically white. Right up to the end, the reader is left guessing which of the two is black and which is white.

Morrison wrote this, her only short story, in 1983. Racial segregation in the US had been legally abolished 20 years earlier but discrimination against the black population was still deeply rooted in society. Denigration, stigmatisation and racism remained in evidence in language.

Morrison’s short story was rediscovered a few years ago and was published for the first time as a book in 2022. It features an introduction by Zadie Smith, a British writer known, amongst other things, for exploring issues of race, religion and cultural identity. The story has lost none of its relevance. Skin colour continues to be one of the factors that determine how people are perceived even today.

Book

Morrison, T., 2022: Recitatif. New York, Alfred Knopf.

https://www.cusd80.com/cms/lib/AZ01001175/Centricity/Domain/1073/Morrison_recitatifessay.doc.pdf

Dagmar Wolf is D+C/E+Z’s office manager.

euz.editor@dandc.eu