Rainbow nation

Changing the conversation

The African National Congress (ANC) party has governed South Africa since the country’s first democratic, non-racial elections in 1994. The ANC won a resounding victory that year, ending the disgraceful apartheid system of racial segregation (see box).

But when the team of the new president, anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela, took office, it found apparent vacant buildings and empty file cabinets. Beyond a steady exodus, much of the civil service, dominantly whites, anxiously hid in their offices fearing retribution and had destroyed those files that recorded their abuse.

Today, 27 years later, things have moved on. South Africa’s government appears to be substantively involved in interracial cooperation. The principle of black majority rule is firmly in place and the civil service is overwhelmingly black. Yet elements of the old racial mistrust persist, and government agencies do not function as efficiently as they should. In a different guise, race and race-driven politics continue to hamper progress, making it harder to spread prosperity.

In the early years after the 1994 election, the outlook for cooperation between the races was promising. Under Mandela’s leadership, the ANC took a non-racial high ground. Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s vision of a “Rainbow Nation”, in which all peoples would come together, served as a basis for genuine reconciliation efforts on all sides. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission exposed the brutality of apartheid, and, to some extent, helped the nation to come to grips with it. South Africa seemed prepared to set its demons aside.

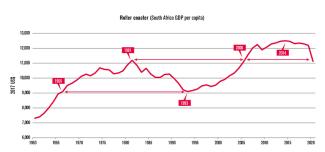

Perhaps reflecting this optimism, South Africa’s economy experienced a 20-year growth spurt. Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita rose from a low of $ 9,100 in 1993 to around $ 12,500 in 2014 (see chart.) Growth accelerated sharply under the government’s 1996 “Growth, Employment and Redistribution” policy. When Mandela stepped down in 1999 his deputy, Thabo Mbeki, became president and continued to pursue growth and redistribution policies to aid the poor.

The growth trend did not last. Per-capita GDP began to decline under the corrupt presidency of Jacob Zuma, a traditionalist who became the head of state in 2009 and who was again confirmed in office in the 2014 election. He presided over a wasted decade – with per-capita GDP eventually plummeting to $ 12,200 in 2019 and then $ 11,100 by 2020 due to Covid-19. His tenure has become associated with “state capture” where private interests subvert governmental decision-making for their own benefit. A judicial commission is still reviewing the corrupt practices of that period.

Zuma failed to rise to South Africa’s most daunting challenges, but he remains popular among a faction within the ANC and many Zulu kinsman. When he was arrested in July because he had refused to cooperate with the judiciary his supporters instigated violence that soon escalated. The subsequent rioting reflected the damage that he did to the state and the frustration many people feel.

Regrettably, racial politics became virulent again in the years of stagnation and decline, giving rise to the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a political party with an aggressively anti-white and anti-Indian message. Its firebrand leader, Julius Malema, has accused the ruling ANC of serving “white monopoly capital”. He claims that whites have remained in de facto control even in black majority ruled South Africa by manipulating the ANC. Agitation along racial lines has made the EFF the third largest party in parliament. It is not an exaggeration to accuse it of reverse racism.

Redistribution policies

The notion of a powerful white minority manipulating the government behind the scenes has thus taken hold in large segments of the population, including some ANC members. The facts show that it is wrong. South Africa has a strongly progressive tax regime that transfers significant sums to poor blacks. Some 19 million of the country’s 60 million people receive grants from the government, and every aspect of government spending is governed by aggressive black empowerment criteria.

Moreover, South Africa’s spending on education is among the highest globally, roughly 6.5 percent of GDP. The government has also continued to make huge investments in expanding access to water, electricity and sanitation. In addition to black empowerment, large sums are spent on creating a black industrial class. The private sector is encouraged and regulated to advance the interests of the black population. Nonetheless, many believe that the ANC is exploiting poor blacks as evidence of large-scale corruption within the party mounts.

In some areas, for example land transfers, progress for black citizens has indeed been slow. The reason, however, is not some kind of conspiracy, but rather administrative waste, inefficiency and corruption. Hiring ANC members for important government jobs was supposed to empower black people, but the result was that many government agencies, especially at the local and provincial levels, have ground to a halt. Many services are simply not provided.

Slow progress also has other causes, however. Insufficient economic growth has limited opportunities. South Africa needs labour-intensive and sustained high rates of growth over several decades that creates new opportunities for all. It would generate additional wealth that could be invested in reducing inequality and deprivation. The country must generate more prosperity if it wants to improve the prospects for its black majority. Only trying to redistribute existing wealth, the focus since Zuma took over, is a dead-end strategy. It will not deliver results.

President Cyril Ramaphosa became Zuma’s successor in 2018. His rhetoric and attitudes are completely different. He has managed to halt South Africa’s downward trend but has been unable to ignite growth given the extent of wastage, policy confusion and lack of accountability that has become a hallmark of government. The Covid-19 pandemic, moreover, has hit the country hard. Ramaphosa is a veteran ANC leader and trade-union activist. He later thrived in the private sector and has become one of the country’s richest persons.

To move forward, South Africa needs a new, inclusive national narrative. It needs to embark upon its own mythmaking – putting forward a positive story of its present and future that focuses on what binds and not what divides. Since race and class largely coincide in South Africa, the focus should shift from race to class-based policies that provide opportunity based on need, not skin colour lest the country remains trapped in the policies that created many of its past crises.

That said, South Africa must keep working on coming to terms with its past, revisiting painful memories to draw useful lessons from them. A new social contract depends on all parties looking closely at how apartheid began, what it meant and how it ended – and then vowing never again to use race as criteria for privilege.

Jakkie Cilliers is the founder and former executive director of the Institute for Security Studies, a non-profit organisation with offices in South Africa, Senegal, Ethiopia and Kenya.

jcilliers@issafrica.org

Update 16 July, 12:30 pm Frankfurt time: The paragrapah about Zuma's arrest and subsequent rioting was added today.