Central Asia

Soviet-era borders cause trouble today

In September 2022, the armies of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan clashed for four days of bloody conflict. At least 37 civilians, including five children, were killed. Schools and other infrastructure were damaged. Children missed proper education for months. In Kyrgyzstan alone, an estimated 130,000 people were displaced.

A similar two-day conflict raged between the two countries in April 2021. Dozens of people died.

A different kind of violence took place in May 2020 when local people from villages in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan disagreed over who owned a spring. This conflict did not involve regular security forces, but 25 persons were seriously injured.

Violence has been recurring in Ferghana Valley since its Central Asian countries gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. The valley is a fertile area, which is today divided between Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. In the 18th century, it had been the Khanate of Kokand, until it was annexed in 1876 by the Russian Tsar Alexander II. Kokand is now an Uzbek city in the modern-day Ferghana Valley.

Paternalism of the Tsars

The current tensions can be traced back to decisions made in the 1920s. At the time, the Soviet Union wanted to maintain a strong grip on the entire territory of what had been the Russian Empire until the Communist revolution of 1917.

It is possible, but futile to discuss whether the Soviet Union was a colonial empire or not. What is certain is that it did inherit the paternalistic approach of Tsars, under whose rule Russia expanded into Central Asia in the 19th century. At the time, Russian leaders were driven by economic interests and strategic considerations. In particular, they were eager to counter the British Empire’s growing influence in the region.

Echoing other European imperialists, the Tsars spoke of a need to bring civilisation to as yet uncivilised lands. The historian Jürgen Osterhammel (2005, p. 12) has defined this “civilising mission” not only as a self-proclaimed right, but even a “duty to propagate and actively introduce one’s own norms and institutions to other peoples and societies, based upon a firm conviction of the inherent superiority and higher legitimacy of one’s own collective way of life”.

Separate Soviet republics

Soviet leaders similarly considered Central Asia to be backward and in need of progress. They arbitrarily drew borders defining separate Soviet republics, which all, of course, belonged to the Soviet Union.

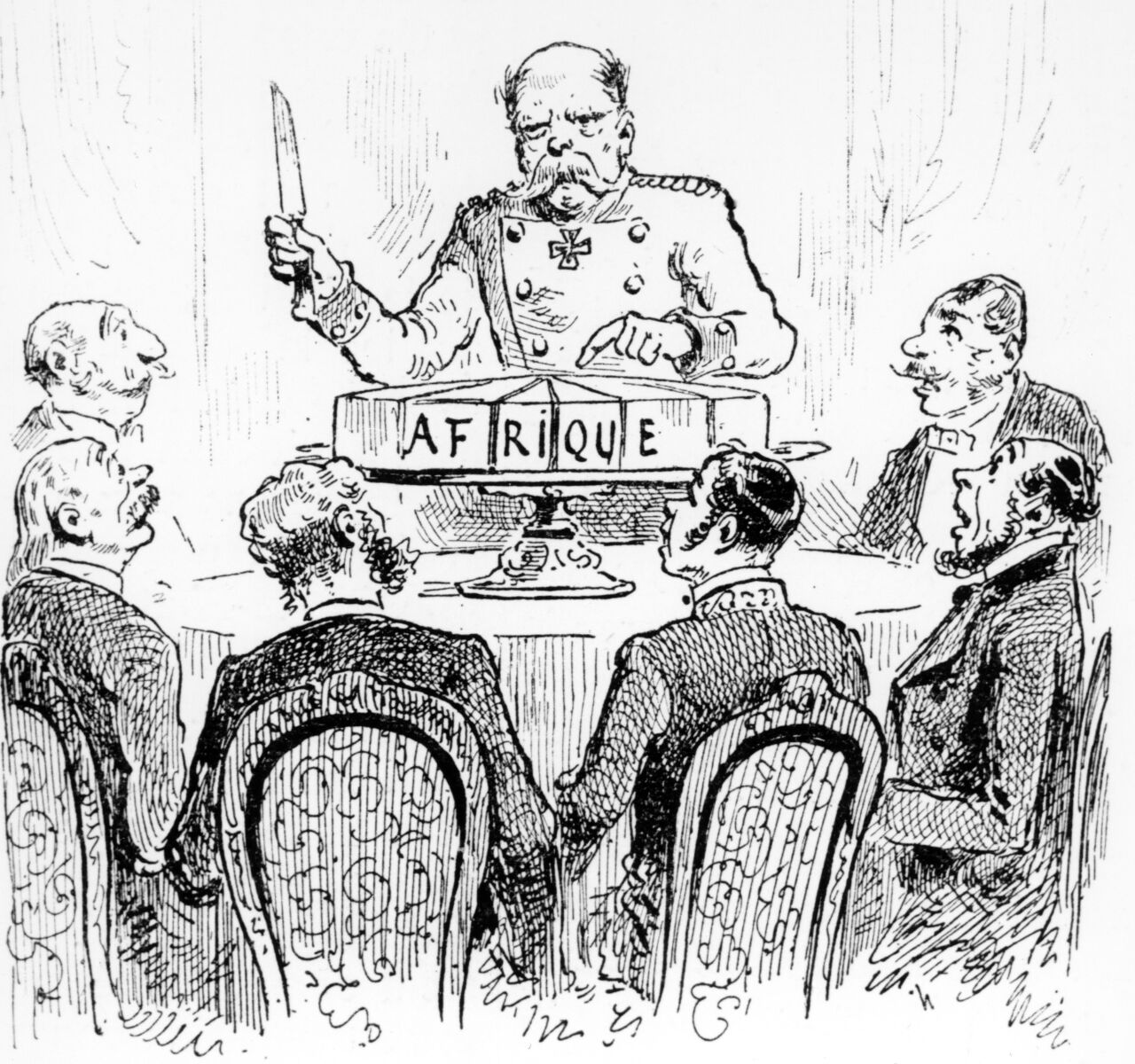

Historians disagree about what motivated the leaders in Moscow to draw the lines the way they did. While they paid some attention to the ethno-linguistic composition of the region, they also ensured that the autonomy of the new republics would stay limited. The approach was top down, echoing the practice of European colonialists who had drawn borders as they pleased in Africa without concern for existing social relations.

In pre-Soviet times, the valley’s population was highly diverse. It was a mix of nomadic Turkic-Mongol speakers and sedentary Persian communities. Different ethno-linguistic groups often lived in mixed towns and villages.

Under Soviet rule, however, three ethnic groups – the Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks – were designated as distinct nationalities. New borders were drawn to create new republics that supposedly fit these newly created ethnic identities and their institutions with newly fabricated pasts. For many practical purposes, however, the Soviet Union’s new internal borders split existing communities, cutting across important social, economic and cultural ties.

Various exclaves and enclaves made matters more complex. The territories of the new republics were not contiguous, so both people and goods had to cross republic borders often. The enclaves were often located in strategically important places which contained key resources, particularly water and fertile land. Vital infrastructure, such as irrigation systems, served people on different sides of borders, necessitating inter-republic cooperation.

Moscow as ultimate arbiter

This arrangement allowed Moscow to maintain de facto control over crucial assets, even as it nominally devolved power to the republics. In practice, what was supposed to facilitate a sense of ethnic self-determination, therefore served a divide-and-rule strategy. Moscow became the ultimate arbiter whenever disputes arose. Accordingly, the Russian language became even more important than it already was.

It is telling, moreover, that Soviet authorities used Tsarist rhetoric to describe “stability”. Their focus on ethnic identities reduced the role of Islam as a common denominator in the region.

As a matter of fact, border disputes erupted immediately after the 1924 division, with both the new Uzbek and the Kara-Kyrgyz republics claiming land on the respective other’s territory. From 1924 to 1927, there were several attempts to adjust the borders. The negotiations involved committees from Moscow, Tashkent and Frunze (today’s Bishkek). A significant update occurred in 1929 when a separate Tajik republic was established.

Divisive international borders

In Soviet times, only administrators really worried about the internal borders. In daily life, these boundaries remained largely invisible as people moved freely between the different republics. That changed in 1991. The collapse of the Soviet Union transformed the administrative boundaries into international borders.

The materialisation of these borders led to three kinds of disputes:

- resource-management conflicts, particularly over water,

- social unrest due to restricted cross-border relations and

- official border conflicts exacerbated by increasing ethnic and national differentiation.

In retrospect, the redrawing of Central Asia’s political map in the 1920s was probably the policy measure of the Soviet era that had the most lasting impact on the Ferghana Valley. The arbitrarily drawn borders keep causing trouble to this day.

Vorukh is a striking example. It is a Tajik enclave surrounded by Kyrgyzstan. For farmers in both countries, the Ak-Suu River – also known as Isfara – in Vorukh is a crucial water source. Water management remains a contentious issue for the two governments. Unsurprisingly, Vorukh was one of the main sites of the two brief armed conflicts of 2021 and 2022 that were mentioned above.

There have been several other instances of trouble. Regional tensions dramatically escalated in early 1999 when Uzbekistan, citing economic and security concerns, began closing its borders with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Uzbekistan has generally taken the most aggressive stance on border control, installing minefields, checkpoints and considering the construction of border walls.

Another notable incident was the 2010 ethnic violence in Osh, Kyrgyzstan. It highlighted the fragility of interethnic relations – as did other regrettable events in the region.

Policymakers have responded to the troubles by trying to better define and demarcate borders. That approach, however, tends to fail. By 2009, the Uzbekistan-Tajikistan border in the Ferghana Valley was largely defined. However, significant portions of the Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan borders remained undelimited and undemarcated. Following the 2021 and 2022 conflicts, the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan border is finally being delimited and demarcated, with latest news indicating only six percent of the border remains contentious. The plan is to finalise the borders by the end of 2024.

Outlook – the future of the Ferghana Valley

One must ask, however, whether it makes sense to focus on separating the different communities in the Ferghana Valley. Attempts to do so are at the root of disputes over resources that are intermixed with complicated ideas of national identity and have fundamentally altered the region’s character. What was once a coherent unit, has become a fragmented region.

The current patchwork of enclaves and exclaves is a source of persistent tension and conflict. Resolving these issues will require not only technical solutions like border demarcation. The region needs a deeper reckoning with the colonial legacies that continue to shape it.

The recurring border conflicts in the Ferghana Valley are a stark reminder of the enduring impact of colonial policies, even decades after the end of formal colonial rule. The Soviet Union’s approach to national delimitation, while ostensibly aimed at empowering local ethnicities, in many ways perpetuated and even intensified colonial practices of divide and rule.

As Central Asian governments navigate these challenges, they should adopt innovative policies that go beyond the rigid ethno-national thinking of the Soviet era. They must finally recognise the region’s long history of interconnectedness. The people in the Ferghana Valley have complex, multi-layered identities that cannot be properly defined along ethno-linguistic lines. Policies that are based on this insight may well prove to be the key to lasting peace.

Reference

Osterhammel, J., 2005: The great work of uplifting mankind. In: Barth, B., Osterhammel, J. (eds): Zivilisierungsmissionen: Imperiale Weltverbesserung. Konstanz, UVK Verlag.

Syinat Sultanalieva is a Central Asia researcher for Human Rights Watch.

sultanalievas@gmail.com

Twitter/X handle: @SyinatS