Op-ed voices

Dimensions of crisis

France: Libération

After Mali, the Central African Republic. Under the command of a Socialist president, the French Army has once more become the "gendarme d’Afrique". These interventions are legally correct thanks to the mandate from the UN Security Council. Both missions are responses to emergencies. (...) The entire political class – with the exceptions of the extreme left and extreme right – supports the operations, and so do all the European allies and the USA, quite content to let the French army step into the front line. After 50 years of independence, African leaders are rallying around the former colonial power and applaud its intervention in sovereign states. (...)

One reason for state failures in Francophone Africa is the unequal, corrupted and corrupting relation called "la Françafrique". Ever since Mitterrand, all French presidents have promised to stop the kind of networking that served elites but never benefited Africa’s people – without results.

Cameroon: L’Effort Camerounais

Many outside the Central African Republic may be indifferent to the plight of thousands caught in the conflict, but the increasing focus on religious differences to justify war and the volatile socio-political situation on the African continent, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, is an irrefutable proof that people in many so-called "stable" and "peaceful" African countries are only potential refugees. (...) Cameroon has contributed a contingent of soldiers – as regional forces and the international community desperately struggle to ensure a return to peace in that conflict-ravished country. But while such efforts usually take months and sometimes years before significant and perceptible positive changes are noticed on the ground, those caught in the conflict through no fault of theirs are finding it more and more difficult to meet their basic needs (published in October).

USA: Washington Post

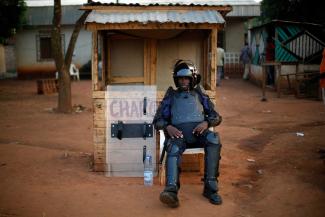

What began as a military coup by the Muslim Seleka coalition this year became a national rampage of looting, rape and summary executions. The conflict has attracted foreign jihadists from Chad and Sudan, set off retribution by Christian militias, caused the collapse of civilian authority and resulted in massive dislocation and food shortages. The international response to the CAR crisis has been relatively swift, though hardly sufficient. The French – as in Mali – have taken the military lead in attempting to disarm militias and hit squads, resulting in recent casualties and significant domestic criticism for President François Hollande. France has emerged as one of the few western countries with its conscience and confidence intact after the global exertions of the past decade. A few thousand African Union troops are also on the ground in CAR, with a few hundred more (from Burundi) being transported by the United States. (...)

Apart from the essential task of protecting civilians from murder, the most important intervention may come in urging CAR religious leaders to reduce tensions – to calm the paranoia on both sides and encourage trust. CAR has a long history of political instability, but not of Muslim/Christian conflict and hatred. Taking religion seriously is an often-neglected aspect of successful diplomacy, and engaging religious leaders, in this case, may be the best way to strengthen the majority impulse of coexistence.

Central African Republic/France: www.centreafrique-presse.info

No, the war in the CAR is not a religious war, nor do the tribes and ethnic groups really exist as entities in themselves apart from everything else. They are merely the continuation of definitions used by the dominant power in the colonial era. Africans will therefore have to construct analytic tools in order to understand better what conflicts can arise in spite of the will to define "us together". Unless that is done, no solution to any of the conflicts will last.