Pamoja Dance Group

A sad tale about elephants

The audience is mostly Kenyan. People talk lively to each other while taking their seats. When the lights go down, however, one only hears the solo-percussionist, playing fast and dramatically. The tension rises, even as the stage is still empty.

Next, two dancers, Sylvester Barasa and Joseph Kanyenje, appear. They are crawling towards each other from both sides of the stage. Sylvester was diagnosed as a child with polio and lost the functionality of his legs. He was abandoned by those who should have cared for him. He was left to survive on the streets. He says he loves dancing: “It takes me to a higher level, a better world,” he says. “I no longer feel disabled.” Joseph is the artistic director of the group and has no obvious disability.

The Pamoja Dance Group includes dancers with and without disability. All are part of Nairobi’s arts community. The Group views its work as support for the government of Kenya in implementing the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disability, which was ratified in 2008. At the same time, it provides a forum for all members to tackle controversial issues that affect society in general.

On the stage, Sylvester moves forward using his strong arms. His presence fills the room. The two men dance. The story evolves in front of the audiences’ eyes. The dancers turn into elephants roaming in the wild, pulling down branches and stripping them of their tender leaves. The music is gay, and the dancers convey a strong sense of community. They have now become herd of eight.

Later night falls and the frogs start croaking in the swamp. The singer Asali gently tilts the beads in her kayamba to the accompaniment of soft flute music from Bruno Mbaruku. The auditorium is so silent one would hear a pin drop.

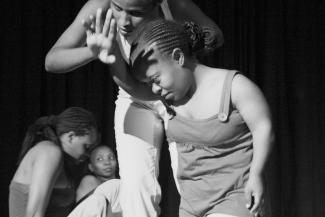

Then Suki Mwendwa and Ruth Mueni emerge onto the state. Suki is a professor at the University of Nairobi and acts as a guest artist in the piece. Ruth Mueni is a dancer, an actress and a Paralympics athlete. She says the major message she wants to pass as an artist is that “we are all able – we just achieve our goals in life in different ways.”

The two women dance playfully. Suki is twice as tall as Ruth, and the difference has a dramatic impact. Like an elephant mother who wants to protect her child Suki stands above her dancing partner when the story takes a dramatic turn: hunters appear and put the elephants’ lives in danger. They want to gun down the bulls for their precious ivory.

The lead bull, played by Sylvester, does not take it lying down. He fights the hunter in his death dance. In the end, the poacher has the upper hand. A sombre mood engulfs the stage as the jumbos succumb one by one. As the story evolves, the elephants are no longer the main characters of the performance. The focus is now on village story tellers, but they assume different roles as they tell their tale, turning into elephants, poachers and park rangers as demanded by the story. The drama is both serious and funny. It reminds the audience of the fact that elephants are emotionally connected to their families and shed real tears when mourning their dead. The piece sends a clear message on the destructive nature of poaching.

The audience follows the story until the very last movement. Although the faces are concealed by darkness, one feels the emotions. When the curtain comes down, everybody is on their feet applauding.

The dance drama is not only staged in Nairobi, however. “We will do this piece in cooperation with the David Sheldrick elephant sanctuary, thus helping the elephants, and bringing culture to places where tourists come together,” says Joseph, the artistic director. “The dancers tell the story of the present day situation of elephant in Kenya.” (ib)

Isabella Bauer is a freelance journalist and consultant. She specialises in East Africa, Southern Africa and Germany.

isabella.bauer@gmx.de