Pamoja Dance Group

Impressive performance

How does the audience perceive your group, especially the disabled dancers?

The first time we performed, people were crying during the first five or ten minutes. Although we did not look at them, we could tell that they were moved, because we just heard people sniffing and sobbing. They must have felt strong emotions.

What do you think moved people so much?

Usually, when you look at a person with a physical disability, you probably think you should feel pity or sympathy. But the dancers you see in our performances are not at all like what you expect: they are performing and doing all kinds of things. So the people in the audience perhaps ask themselves: “Why am I pitying this person? Look what he can do!” This is so emotional. But this sensation only lasted a few minutes. When they continued watching us, they stopped seeing people with disabilities trying to dance – they started watching dancers.

What makes you most happy about dancing with this group?

It’s two things: the commitment of the dancers and how they have changed since 2006. Some of them are really not the same persons they were when they first came here. When they grow up, they are given so many names. And even now, as adults, they are given so many politically correct names: handicapped, disabled, or people with disability. They were always labelled one way or another, rather than taken as the persons they are. But when they join us, I call them dancers. From that point on, this person is going to be a dancer.

That sounds like a very special work relationship.

Yes, it is. Sometimes I ask them to do difficult things when we dance, but they understand that I must challenge them. And they allow me to challenge them and know that I understand them. We come from completely different backgrounds, but I keep on learning about them and they keep learning more about me. This exchange makes it very exciting to work together. Change is what I see in my dancers – and also inside myself. Previously, I perceived things and looked at people in a different way. I now know they can come up with movements and emotions that can blow your mind. And some of them are not even aware of it! Me too, I am an actor, but I cannot bring out this emotion. I may need words or a song to express certain things, but they often don’t need any of this – their bodies say so many things.

How do you choose the stories for the performances?

Sometimes the ideas evolve from the workshops we hold. In these workshops, I may tell them to move as if this room was sticky like glue, or scratchy like sand. Then we see which emotions come up and what it reminds them of – and the story develops from there. Or I come up with a story myself – but it will keep changing as our work progresses. Some time ago, I suggested a story from Uganda, about what happened under the regime of Idi Amin, when he killed so many people and dumped them into Lake Victoria. But then everyone came up with their own ideas, saying: “Oh, this reminds me of Ruanda” or “This is like what the city council is doing to the hawkers now”. So the story changed. It was still a story about oppression, but everyone had their own version of oppression. So we ended up calling the peace “brother and sister”, telling all these different stories of oppression.

Who is playing the oppressor, and who is the oppressed in this case?

Sylvester, a brilliant dancer without legs, and me are performing the lead dances. And it is funny that he will be the oppressor and I will be oppressed. Because he is quite strong and he has such an expression on his face when he is dancing.

Are some of your stories directly linked to Nairobi?

Yes, sometimes we find our stories in Nairobi. Our piece Koncrete City was developed by walking around in the city. Everyone in the group was complaining how inaccessible the city is, so they took me round and showed me places. “Look Joseph, this is supposed to be an office for disabled people, but look at the stairs! How am I supposed to get up there?”, one of our actresses said. She calls it “stairs to heaven”, because there are so many. Another one complained about the matatus, the shared taxis, because their steps are too high: “How am I going to board a matatu?”, she said. Everyone had their own version of the Koncrete City. But we decided to make it a fun piece. Yes, we have problems to climb stairs to heaven and to get into matatus, but that is not what we were going to show. We wanted to show: in this Koncrete City, we would like to have fun! So we made it a fantasy kind of place.

How did you become the artistic director of the Pamoja Dance Group?

This group existed before I became the artistic director. It was founded by Miriam Rother. She left Nairobi in 2008 and I took over from her. I actually went to one of their performances, because a friend, a dancer, told me that this was an amazing group. When I watched them, I could not believe what I saw. When the piece was over, the audience clapped and was completely taken. But we just stayed on our seats. I could not move away. Somehow Miriam must have seen this and she came up to me. We shortly talked and she asked: “So, are you coming?” And I said yes. That was how I came to the first workshop. And shortly after, I started to work with them.

What does it mean for you as a professional dancer to work with this specific group?

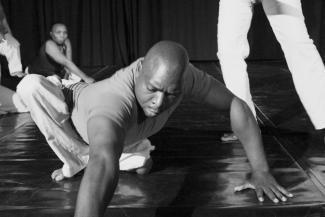

When I came in first, I thought: Let me show them how to dance. I thought I must be a better at it, because they have disabilities, and because I have had some training as a dancer. I dance a lot on the floor, which is quite difficult for most dancers. But when I came in here, I made a completely new experience. As most of these dancers have disabilities, the floor is where they normally are. Moving on the floor was what I thought I was an expert in. But these people who had moved all their lives on the floor were much better at it than I was.

What was the consequence?

It actually forced me to find more standing movements, so that we could find complementing movements in our performances. Yes, I am able-bodied, as people say. But their ability is far more advanced than the one I have.

Where do you see the major difference between people with and without disability?

We take for granted how we are. We don’t think we should be aware of how we stand, how we walk – we just do it. But they had to explore their body to deal with their physical challenges. So they know themselves better; they are so much more aware of their bodies. And they made me improve and become much more aware of how I am too; of how my body can work and what it can do. Actually, I came to the conclusion, that I myself have some disabilities. They can do so many things that I can’t.

What do you think are the most important abilities a dancer on stage needs to have?

Truth and conviction matter most. Dancers need to be true, true to their movements, to everything. They need to convince the audience through their movements and show them what they want to tell. You can do anything – jumping or moving around – but it does not help if you don’t have the conviction.

Joseph Kanyenje is the artistic director of the Pamoja Dance Group.

http://www.pamojadance.org/Pamoja_Dance/Pamoja.html