Economic policy

Bypassing the poor

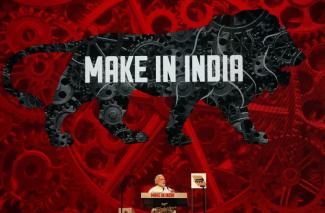

In 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a major manufacturing initiative, inviting companies and countries to invest in manufacturing facilities in India. There has been much global applause for “Make in India”, although it is actually a repackaged version of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s National Manufacturing Policy, which had been launched in 2011.

Singh’s policy promised to create 100 million jobs in manufacturing by 2021 and increase the sector’s share of India’s gross domestic product from 16 % to 25 % with a focus on innovation and job creation. Modi promises the same, allowing 100 % FDI ownership in about two dozen focus sectors. In three sectors, the new allowed FDI shares are lower: 74 % in space industries, 49 % in the defence sector and 26 % in new media.

The government promises to build the infrastructure that manufacturing companies expect, train workers in relevant skills and even voluntarily recognise intellectual property rights, for instance for pharmaceuticals, even though WTO rules do not force it to do so. The idea is that domestic and multinational corporations will invest in production capacities in India in order to serve export markets.

Backed by a massive international public relations campaign, “Make in India” has let to some commitments for FDI. A “Make in India Week” held in Mumbai in February attracted government delegations from 68 countries and business teams from 72 countries.

Actual capital inflows show a different picture though: more than 60 % of FDI equity inflows totalling $ 24.8 billion from April 2015 to November 2016 came from two countries: Singapore and Mauritius. And even the government concedes in an official economic survey that some of these inflows might not constitute actual investment but diversions from other sources to avail of tax benefits under the Double Tax Avoidance Agreement that these countries have with India. Nevertheless, the capital inflow has reduced India’s current account deficit and is good for the country’s credit rating, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

Whether the labour market grows as promised, remains to be seen though. Experts question the labour-intensiveness of the manufacturing investment. “If 11 people were needed to execute a piece of work that generated 1 million rupees worth of industrial GDP a decade ago, today only six are needed,” says D.K. Joshi, chief economist at the ratings and research firm Crisil. In the election campaign, Modi promised the young generation 10 million new jobs a year. The jobs are needed, but are not available so far.

Meanwhile, the banks present terrible balance sheets, and the government is getting rid of its head of the Reserve Bank, Raghuram Rajan, who refused to toe the ruling party’s line. Even the export data brings no cheer: India’s merchandise exports declined in July by 6.8 % to $ 21.6 billion while imports declined by 19 % to $29.4 billion. Many export-driven production sites have been shedding jobs. All in all, only 5000 new jobs were created in the first half of the current fiscal year, after 271,000 in the equivalent period of the previous one. The showcase automobile sector alone saw 23,000 job losses in export units.

Ocean of mediocrity

India’s manufacturing industry is made up of islands of excellence in an ocean of mediocrity. Its contribution to the GDP is stagnating at 16 %, and from 2005 to 2012 it did not even create 10 million new jobs according to an OECD research paper (Joumard et al., 2015). Given that India has 1.2 billion people, that number is minuscule. Skilled labour and infrastructure are lacking. Enterprises with fewer than 20 staff account for more than two thirds of manufacturing employment.

India has not gone through the classical transformation from the primary sector (agriculture and natural resources) to the secondary sector (manufacturing) and then tertiary sector (services). Instead, the country jumped right into services, thanks to a large number of people who are proficient in maths and English and satisfy global demand for data processing. However, even IT services are in trouble with declining global orders, though there is some good news in the financial-services sector. The bottom line is that the government’s agenda seems to have veered away from what ordinary Indians need.

It is worrying, for instance, that the government is pleasing the international pharmaceutical lobby by accepting IP rights. As a result, vital, low-cost medicines may become more expensive. That would please multinational corporations but thwart affordable health care for poor people.

Modi has other priorities. Thanks to his diplomatic efforts, the USA has formally recognised India as a “major defence partner”. The rapprochement will make it easy for India to access sophisticated US weaponry and technology in order to modernise its army and arms sector. How much of it will actually be made in India is not clear.

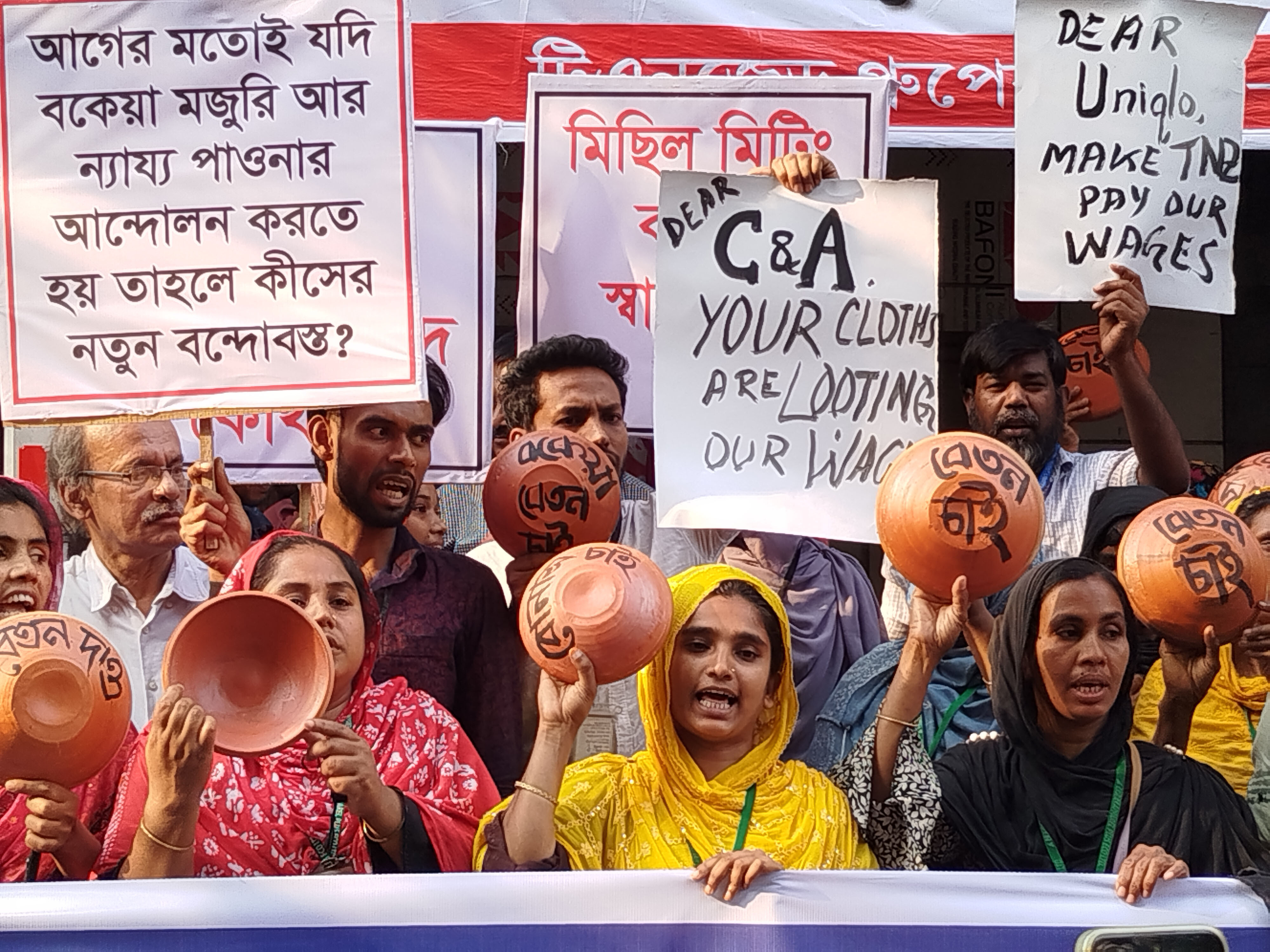

Going by current indications, the industry leaders in all sectors are not very enthused about the investment environment, and sceptics believe that ultimately, “Make in India” will lead overseas manufacturers to set up shop in India. They will exploit cheap labour, benefit from government subsidies and take advantage of lax laws on environmental protection and occupational safety.

Government rhetoric puts things differently, of course. Modi likes to speak of “zero defect, zero effect”. This slogan implies that all manufactured goods will be so flawless that foreign buyers will not want to return them, and that environmental protection will be so stringent that nature will not be harmed. This is easier said than done. One of the showpieces of the “Make in India” campaign was an Indian smartphone that would cost the equivalent of merely four dollar. It ended in embarrassment with the first 5 million phones being imported from Taiwan.

The prime minister obviously wants to emulate China. But India does not have the same preconditions. China is a dictatorship that neither permits independent trade unions nor respects labour rights. For obvious reasons, India’s trade unions oppose “Make in India”.

China’s initiative to produce goods for the world market, moreover, was launched when the global economy was expanding, and its cheap labour and low-cost facilities attracted world-class technology. India missed that boat. On the other hand, India already has private-sector corporations that perform strongly on the world market, and manufacturing does not need to be kick-started with FDI (see D+C e-papers 2015/12, page 20 and 2016/02, page 32).

The country should focus on areas where it has a comparative advantage and foster policies to make society inclusive. This means paying attention to farming and food security, focussing on environmental health and promoting energy security based on renewables. Social and health infrastructure, first-class civil infrastructure and a fast-working bureaucracy are prerequisites for the kind of growth that could free 500 million Indians from poverty. The approach of “Make in India”, in contrast, is likely to bypass the poor.

A worrying trend, moreover, is that foreign portfolio investors are becoming ever more influential players on India’s stock market. Perhaps India should learn a different lesson from China’s example. Foreign investors have increasingly been attracted to the People’s Republic because they want to sell goods to its huge population. India’s population is almost the same size, and if it had the same purchasing power, it would be just as attractive.

Link

Joumard, I., Sila, U. and Morgavi, H., 2015: Challenges and opportunities of India’s manufacturing sector. OECD.

http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/challenges-and-opportunities-of-india-s-manufacturing-sector_5js7t9q14m0q-en