South Asia

Huge challenges

Since Independence from the British in 1947, agriculture has always been the major feature in economic policy making in India. The reason is that agriculture provides employment to the largest number of people in India. According to the 2011 census, more than 50 % of the population depended directly or indirectly on agriculture and related industries.

Policymakers' focus on agriculture has delivered results. The Green Revolution that set in in the mid-sixties has dramatically raised productivity. It was based on mechanisation, irrigation, improved seed, fertilisers and related matters. India's harvests of rice, wheat and potatoes have risen spectacularly.

In recent decades, the nation has been producing enough food to feed itself even though the population has more than doubled from 550 million in 1971 to more than 1.2 billion in 2011. Agriculture-related infrastructure (irrigation canals, roads, marketing facilities, agricultural institutes et cetera) has helped to improve food security.

In West Bengal, rice yields have increased dramatically thanks to the Green Revolution and a land reform. The latter was called Operation Barga and implemented by the Left Front state government that won the elections in 1977. Basically, Operation Barga was about registering sharecroppers, strengthening their legal position vis-a-vis the landowners and entitling them to a fair share of the harvests.

The state government's Agriculture Department supports the farmers through various extension programmes, informing farmers about new scientific trends. Moreover, it recommends specific kinds of hybrid seeds, fertilisers and pesticides. To some extent, it distributes such farm inputs. On top of all this, a Kishan Credit Card (KCC) scheme has been introduced. It is designed to give farmers better access to financial services.

Scientific methods have changed traditional farming and raised productivity. Many farmers regard technology and especially innovative seed as a blessing. The most important changes are:

- Hundreds of traditional seed varieties were replaced with a few high-yielding varieties.

- Home-made bio-compost or cowdung manure has been replaced by chemical fertilisers.

- To some extent, manual systems of irrigation have been replaced by fuel- or electricity-powered equipment. Similarly, thrashing machines and tractors have become common.

The most important change, however, is that the farmers no longer work in a basically self-sufficient manner. They used to depend on the landlords, now they depend on the government and various private-sector companies as well.

Farmers’ concern

There is a downside to the Green Revolution: the new approaches do not look environmentally unsustainable. In our village, the yields on many plots have dropped by half. Adding more fertiliser no longer results in better harvests. Groundwater resources are being depleted. Biological diversity has suffered tremendously, and there are hardly any forests left in our region.

Climate change compounds these worries. The weather has been becoming increasingly erratic in recent years, and the Monsoon rains seem less predictable than they used to be. Farmers worry because the soil is getting too hard and parched to hold water for long.

At the same time, class divisions between landlords and landless villagers have resurfaced. The farmers who have more land became front runners in taking agricultural loans and subsidies from the government, banks and companies. But the tribal and marginalised people, who account for at least five percent of West Bengal's population, are landless, though some do own very little plots.

Marginalised people did not benefit much from the region's agricultural progress, apart from being hired by wealthy farmers as daily labourers for a few more days. Matters are worse in states that did not implement landreforms because sharecroppers have even fewer rights their.

Young village people who get an education do not consider farming an attractive livelihood. They are interested in salaried jobs in towns. Farming, in their eyes, is slow and time-consuming, and it requires hard physical work. Those who stay engaged in agriculture basically have no alternative, though some, especially older people, are emotionally attached to farming. The irony of Indian agriculture is that the educated people who understand the science of farming do not work in the fields, so they do not disseminate their knowledge to villagers.

Many old-style farmers hardly know what kind or how much fertiliser and pesticide is needed for a certain area of land. They often rely on the information provided by shop keepers, who lack expertise themselves, but certainly want to sell as much farm inputs as possible. Due to lacking precaution in handling farm chemicals, many domestic animals, and even people, have died.

All in all, many farmers are desperate in spite of the Green Revolution. Debts, in particular, have driven some to commit suicide. Their plight has even attracted international attention in recent years. The greatest worry, however, is the harmful effect caused to agriculture and the environment in general by the depletion of underground water resources and the uncontrolled use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

Damage control

Realising the problems, the state government is now trying to motivate farmers to cultivate crops that need less water. Moreover, extension officers promote rainwater harvesting and the use of vermin and bio compost. They also advise farmers to gear their production to market demand, emphasising high-value goods such as vegetables and fruits. The basic idea is to use natural and human resources more economically.

However, many farmers are not convinced. They feel confused: “We did what the government officials told us,” says one Santal farmer. “We experimented with new seed, fertilisers, pesticides, and we sold off our oxen and now use the tractor. But after seeing these side effects they tell us to return to the former methods.”

Besides government initiatives, various non-governmental organisations are involved in agricultural development in our area. Manab Jamin, for example, promotes organic farming and trains farmers in practices like crop rotation and mixed cropping.

The organisation is also engaged in marketing organic vegetables in a nearby town, collecting produce from the farms. However, only some well-to-do consumers buy organic vegetables, whereas the general public stays away because of the higher prices. Manab Jamin is path breaking nonetheless, proving the viability of chemical-free farming.

Our own self-help organisation, the Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha, is doing its best to support farmers too. We are running an organic orchard for example. Moreover, we have begun mushroom cultivation and aquaculture fishery. We promote chemical-free vegetables cultivation, bee keeping and farming.

There are limits to what we can achieve however. Most of the land we cultivate does not belong to our families, but to non-resident landlords. It is difficult to create attractive new jobs in agriculture for young people. We would like educated youngsters to become drivers of rural change, but so far, the political economy of West Bengal's agriculture does not give us much scope.

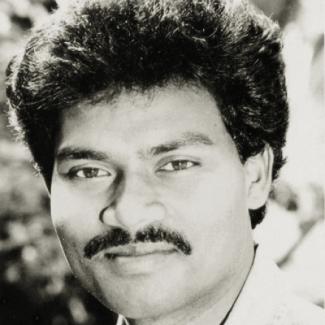

Boro Baski works for the Ghoshaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha, a community-based organisation in two Santal villages. It gets support from the German NGO Freundeskreis Ghosaldanga and Bishnbati.

borobaski@gmail.com