Internet culture

When humour and tragedy go hand in hand

In Kenya – as everywhere else in the world – the growing popularity of social media platforms is being accompanied by the rapid spread of memes. The term refers to media content such as images, videos, audio or text of rather limited size that is predominantly humorous and easy for users to quickly copy and share with slight variations. Memes are an important part of internet culture.

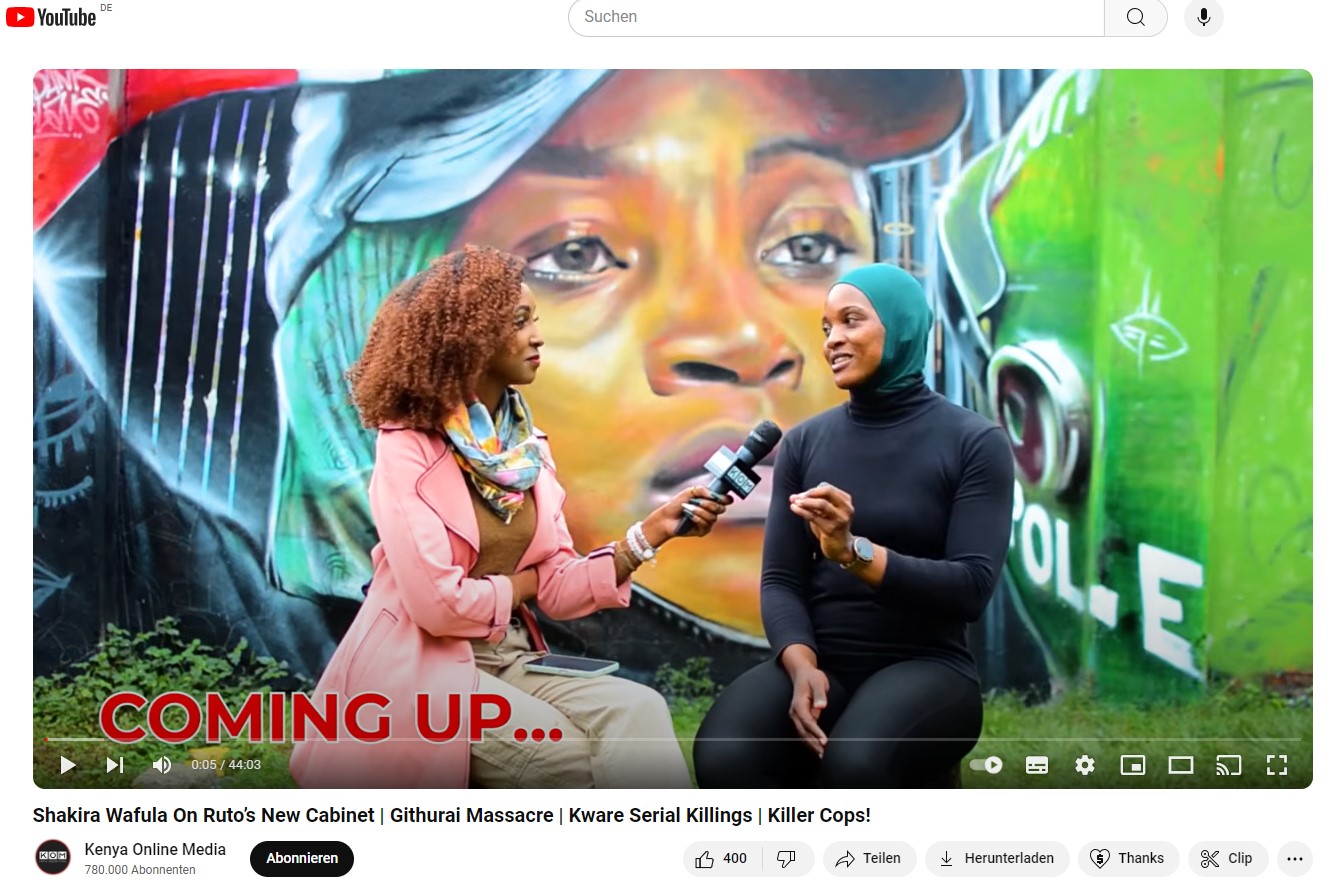

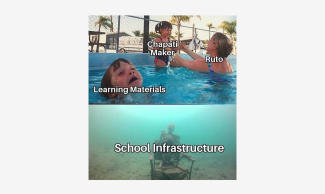

The creators of this content are referred to as “meme lords” in Kenya. These are sometimes individuals and sometimes accounts such as Karis Memes, Funny Kenya Memes or Kenyan Memes Page. They post their content on social media sites and messengers where other entertainment pages then share it. Thus, memes like the one on the right and many others have gained great popularity and created a sense of belonging among Kenyans, especially on X, Instagram, TikTok and Facebook. Many memes have political content and are based on current news from traditional media.

Satire and political humour have a tradition in Kenya. For example, the television station NTV Kenya used to air a programme called “Bull’s Eye” after the nine o’clock news from 2015 to 2022. The satirical show took a hilarious look at recent sociopolitical events and poked fun at the country’s elites and increasingly unpopular politicians. Viewers were able to call in live by phone.

Criticising the government

Memes can also express political opinions directly. Kenyans use them as a tool to humorously criticise the government and the state of democracy in their country. Last year, for example, when the Kenyan youth demonstrated for weeks against the government’s financial policy, social media was flooded with various memes. Some users employed memes for political education, while others used them to mislead political opponents and distract from the real issues.

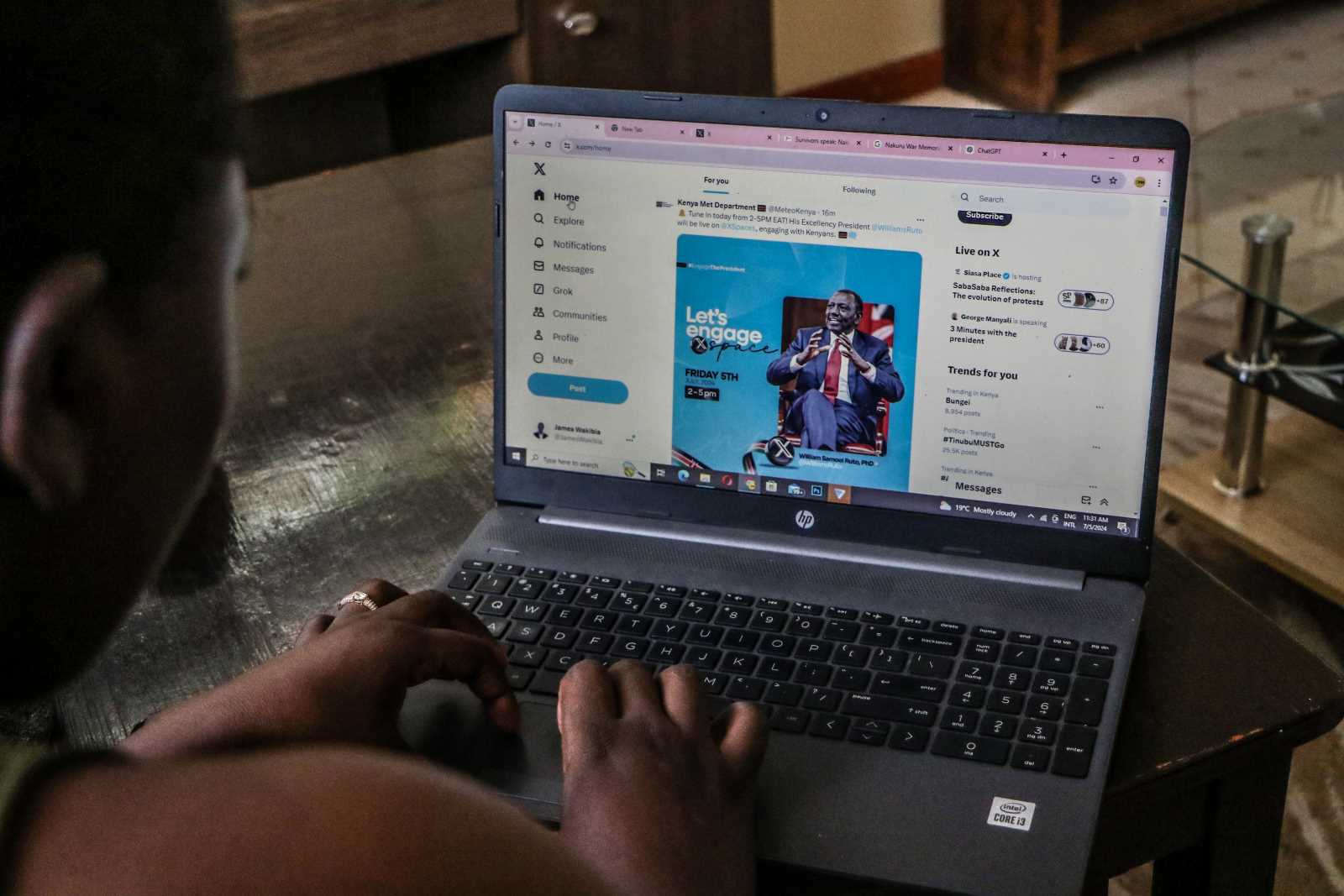

During the protests, the use of memes as a coded form of communication increased: Only those who knew the allusions and double meanings could understand them. The exchange of memes as well as other content increasingly took place on Instagram and TikTok – beyond mainstream media such as the major TV channels.

Gen Z evidently lost faith in President William Ruto and the ruling coalition Kenya Kwanza (“Kenya First”). They looked for ways to demonstrate their frustration and linked memes to hashtags such as #siasambaya (“bad politics”) or #zakayoshuka (“Zacchaeus climb down”). The latter likens Ruto to the infamous tax collector in the Bible, who abused his power and took more from people than he should have. In memes, Ruto is also referred to as “Kaunda Uongoman”. The first part of the name refers to his fondness for the Kaunda suit, a two-piece garment that is particularly popular in East Africa. The second part means that he is a liar.

Ruto has in the past welcomed the use of humour in politics and used it as a tool for shaping public opinion. Now he is calling on Kenyans not to use humour to harass and defame others. For example, he gave a speech in which he criticised a popular meme for depicting him lying in a coffin, complaining that matters of life and death were being treated as a joke.

Unfortunately, the protests against government policy did indeed quickly escalate into a matter of life and death. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, a government watchdog and advisory body, recorded 82 abductions of young people between June and December of last year. They are linked to attempts to silence dissenting voices. Due to public outcry and condemnation by human-rights organisations, some of the abductees were released at the beginning of 2025. However, many are still missing.

Alba Nakuwa is a South Sudanese freelance journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.

albanakwa@gmail.com