Commodities

Missing billions

Tax evasion by international oil, gas and mining companies costs resource-rich countries billions of dollars in lost tax revenue every year (see also D+C/E+Z e-Paper 2017/03, p. 12). According to estimates by the UN and the World Bank, the total sum amounts to a double-digit billion figure.

Non-payment of taxes has serious social, economic and political consequences. The countries affected lack the money for basic public services. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), investing an annual $ 8.7 billion in health care in 46 African countries would save the lives of 4 million children a year. And $ 5.2 billion per year would be enough to pay for the teachers needed to allow every child in Africa to go to school.

Tax evasion and avoidance thus have an enormous impact. Governments of countries like Zambia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chad, Niger or Liberia spend less than $ 6 billion a year. While it is true that some African presidents embezzle part of their countries’ revenue, corruption committed by politicians and civil servants makes up only a tenth of the amount that African countries lose due to tax avoidance by corporations, according to the research organisation Global Financial Integrity.

Because of lost tax revenues, countries in question struggle to develop sustainably and build strong economies. To promote entrepreneurship and create jobs, countries need basic infrastructure that includes streets, electric power, schools and research facilities. They must also be able to grant loans to encourage investments and new businesses. Without tax revenue, governments cannot provide these things and thus depend on outside help. According to numbers collected by the policy watchdog Global Policy Forum, the revenue lost is comparable to the amount of official development assistance (ODA) that sub-Saharan Africa receives.

It will be next to impossible to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) if tax evasion and avoidance continue unchecked. According to UN estimates, between $ 750 and $ 1.3 billion in public spending will be needed each year to implement the 2030 Agenda worldwide. ODA will certainly not cover the entire costs.

Trickery and deceit

Multinational corporations and the natural resource sector use many tactics to avoid paying taxes. Even as they are negotiating mining contracts, companies use their negotiating power, their knowledge of contract clauses or plain bribery to ensure that they are exempt from certain taxes either entirely or for a long time.

Another trick is what is known as transfer mispricing. The company sells the commodity it has extracted to a subsidiary in a tax haven for far less than the market price. This means that the company makes little profit in the country where the commodity is produced and pays very little tax accordingly. On the other hand, very few taxes are incurred in the tax haven where the profit was shifted to. The country’s low tax rates are what makes it a tax haven after all. If such no- or low-tax countries did not exist, companies would have fewer opportunities to evade and avoid taxes in commodity-rich countries. Dishonest practices are also used to avoid paying value-added taxes, excise taxes, licence fees and dividends.

Double taxation agreements can be used to avoid taxes as well (see Catherine Ngina Mutava). They spell out which country an international corporation will be taxed in: for instance in the country where its corporate headquarters are located or in the country where it earns its profit. The point is to avoid taxing it twice. But many of these agreements were designed in a way that disadvantages poorer countries.

The use of double taxation agreements to evade taxes is not illegal, but it is extremely dubious in moral terms. The international non-governmental organisation ActionAid has demonstrated as much with the example of an Australian mining company that operates in Malawi. In order to avoid taxes in Malawi, the company made use of a tax treaty that existed between Malawi and the Netherlands. It established a subsidiary, with no employees, in the Netherlands and sent its Malawian money there. The tax rate in the Netherlands was zero percent, so the money could flow without deductions on to the company’s headquarters in Australia. Over six years, the company thus saved $ 27.5 million it would otherwise have had to pay Malawi’s tax authority.

This case is not exceptional, and the sum in question is comparatively low. According to the Dutch NGO SOMO, an oil company once tried to evade tax payments of more than $ 400 million in Uganda. After lengthy court proceedings, Uganda was at least able to collect a portion of that amount.

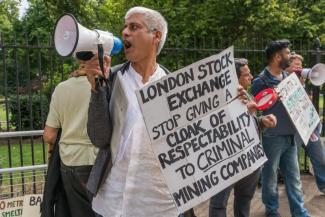

Many of the affected countries are demanding that their interests be taken into account when it comes to the taxation of international companies, particularly in the mining sector. At the UN Conference on Financing for Development in July 2015 in Addis Ababa, a group of 134 developing and newly-industrialising countries insisted that an inter-governmental commission be created at the UN level. They hoped that it would give them a greater say in international negotiations on tax matters. However, many western countries rejected the request, so nothing came of it. So far, international decisions concerning tax issues are still primarily being taken by members of the G20 in the context of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), which is an umbrella organisation of rich nations (see Mick Moore).

Nico Beckert is a freelance journalist and campaigner on commodities issues at Haus Wasserburg in Vallendar.

nico.beckert@gmx.net

Blog: www.zebralogs.wordpress.com