Global governance

Fighting for democracy at home is not enough

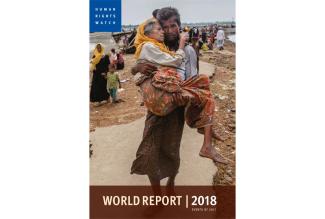

The international community is currently not paying sufficient attention to violence and arbitrary state action. HRW argues that the suffering in Yemen, Syria and Myanmar is being exacerbated because the perpetrators of serious crimes feel free to act. Western governments increasingly tend to look away.

According to Kenneth Roth, the organisation’s executive director, the USA is led by “a president who displays a disturbing fondness for rights-trampling strongmen and the United Kingdom preoccupied by Brexit”. Roth argues in the report keynote that these two “traditional if flawed defenders of human rights” are no longer playing the global roles they used to. Because of racist and anti-refugee activism in Europe, Germany, France and other countries have not filled the gap. Roth states that democracies such as Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, Japan and South Africa should also be doing more.

The good news is that, according to Roth, the wave of right-wing populism in the west looks weaker than it did one year ago. He applauds French President Emmanuel Macron for winning last year’s election by confronting the right-wing Front National (FN) head on. His principled stance, Roth argues, allowed him to prevail over FN candidate Marine Le Pen with a huge margin. The HRW leader praises Macron for standing up to “autocratic rule in Russia, Turkey and Venezuela, and a willingness to support stronger collective European Union action against Poland’s and Hungary’s assault on rights”. However, Roth wishes the French president was less reluctant to confront rights abuses in China, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Roth points out that centrist and centre-right leaders of other European countries have tried to pre-empt the populists’ appeal by adopting some nativist positions, but such strategies only made populists stronger. That was the case in Austria, the Netherlands and the German Land Bavaria, for example.

With regard to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the HRW director states that forming the new federal government was made difficult by the fact that the populist AfD won seats in the Bundestag in the September elections. Roth insists, however, the AfD was strongest in those areas where mainstream politicians copied their approaches and weakest where they were firmly resisted. Roth concludes: “Principled confrontation rather than calculated emulation turned out to be the more effective response.”

With regard to the USA, Roth also has some good news. He states that President Donald Trump is destructive, but he finds the broad resistance his administration is facing encouraging. Civil society, the media, judges and even some members of Trump’s Republican party have limited his impact. In a similar way, Roth praises civil-society activism in Poland and Hungary.

Fighting for democracy and the rule of law at the national level is good, Roth argues, but it is not enough. In this context, he refers to Saudi Arabia and Libya, for example:

“With a seeming green light from western allies, Saudi Arabia’s new crown prince, Mohamed bin Salman, led a coalition of Arab states in a war against Houthi rebels and their allies in Yemen that involved bombing and blockading civilians, greatly aggravating the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Concern with stopping boat migration via Libya led the EU – particularly Italy – to train, fund and guide Libyan coast guards to do what no European ships could legally do: forcibly return desperate migrants and refugees to hellish conditions of forced labour, rape and brutal mistreatment.”

Roth also points out that the lack of western powers’ involvement in human-rights issues gives scope to authoritarian regimes, including especially those of Russia and China, to violate human rights at home and encourage abusive action abroad.