Democracy protection

Protecting democracy, averting autocratisation

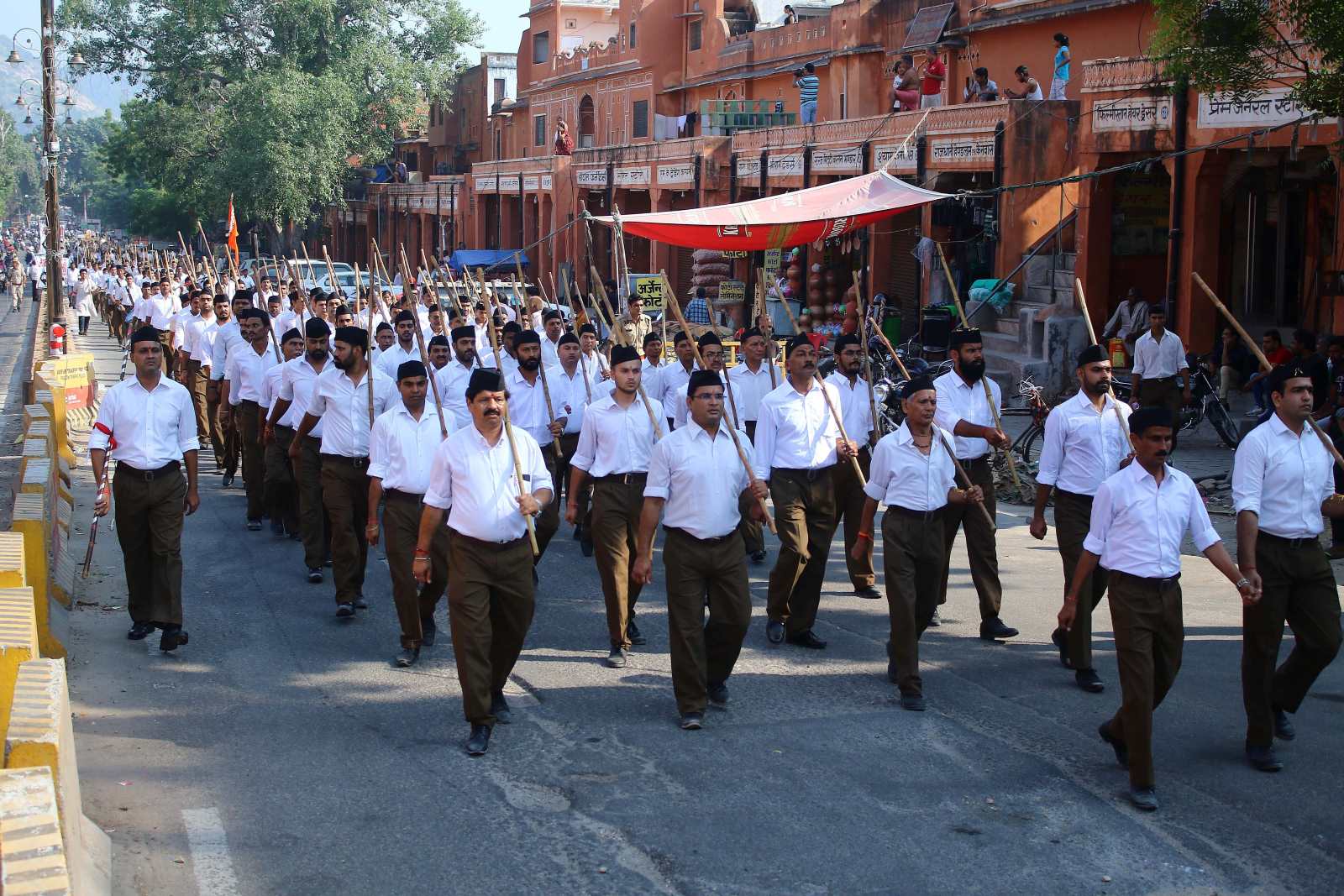

In many democratic countries, including Germany, people have recently protested loudly because they are dissatisfied with politics. More than a few are calling democracy itself into question. At the same time, 72 % of humanity currently lives in countries with autocratic features, as V-Dem, a renowned institute for democracy research, stated in 2023. India, for example, is on paper the largest democracy in the world, yet the government curtails the basic freedoms of parts of the population. Last year’s military coups in Niger and Gabon also point to a resurgence of autocratic rule.

Nevertheless, there are reasons to remain optimistic and support democracy as a political system – through both development and foreign policy – particularly in response to rampant autocratisation. The democracy support of the past 20 years is outdated, however. A new approach is urgently needed.

On the one hand, the goals of democracy support have changed: they now increasingly include the protection of democracies from autocratisation. Achieving these goals will require different strategies, some of which will still need to be developed. On the other hand, sound knowledge now exists about the proper conditions for and the impact of democracy support, as well as the impact of development policy on democracy. This knowledge should be used to craft a new approach.

Research shows that democracy support works: on average, the funds used make a significant contribution to improving democratic institutions, procedures and behaviours. Evaluations of individual projects in areas like election monitoring, promoting civil society and strengthening parliaments frequently show at least a partial impact.

Expectation management

However, no state can – and should attempt to – democratise an entire political system from the outside if the local society and at least part of the government elite are not on board. This is illustrated, for example, by the international intervention in Afghanistan until 2022. Overly ambitious political goals and expectations are one of the main problems in democracy promotion.

Instead, promoting and protecting democracy “from the outside” means supporting democratic elements in a political system and society over the long term, as well as responding quickly at the right time, like during an upheaval such as the Arab Spring in 2011/2012. Managing expectations appropriately and establishing long-term relationships are therefore key.

Characteristics of the current wave of autocratisation

The development of political regimes has no set outcome, as can be seen, for instance, in the current autocratic movements in democracies like the USA or India.

Societies’ political values can change, and democratic institutions can be dismantled, even if they have formed over centuries. These fluctuations between autocracy and democracy have been occurring in waves since the beginning of the 20th century. At the moment we are at the peak of an autocratisation wave. It has three characteristics:

First, autocratisation is now less likely to happen through an abrupt breakdown of democracy, like a military coup, but rather through a gradual process. Frequently it is democratically elected officials themselves who dismantle democracy. Insofar as these are partner governments for state development policy, countries must consider what this means for cooperation and whether consequences should follow.

Second, there are no simple classifications of political regime types. Autocratisation processes and autocracies that are currently emerging differ from each other. Whereas some states still hold elections while restricting freedom of expression, elsewhere, those in power can govern without checks through the population or parliament and judiciary. This variance determines the choice of the right means of promoting and protecting democracy.

Third, democratic decline is a problem shared by societies in both the global north and global south. This process is often accompanied by polarisation. Divisions first appear among a country’s political elites, then among its social forces. This trend makes it more difficult to reform the democratic order and bridge divides.

Creating more knowledge

These characteristics of autocratisation present international democracy support with new challenges, which are nevertheless solvable. Democracy protection and autocratisation prevention are now central working fields. However, there are few generalisable findings on modes of action, instruments or the right moment for international intervention. The main task is to pool the evaluation findings to date, analyse past activities and, if necessary, modify and expand them. Suitable instruments are needed in order to appropriately analyse political contexts and recognise differences.

Last but not least, democracy protection is also a question of attitude. A country like Germany can hardly promote democracy in other countries without examining the underlying values and viability of its own democracy. The pivot in democracy support must therefore also lead to better understanding in Germany and Europe and with societies in the global south. Democracy support in this sense would be a mutual learning process.

When development policy strengthens autocracies

Still more is required, however, to effectively protect democracy and prevent autocratisation. What is needed is a fundamental re-examination of the entire development policy – a mammoth, but unavoidable, undertaking.

Research shows that development policy support strengthens existing political dynamics. It can support democratisation, but also indirectly stabilise autocratic rule. An OECD study revealed that in 2019, 79 % of all public development funds worldwide went to autocracies. These funds give those in power financial and therefore also political leeway to invest in areas that serve to expand or maintain their power (fungibility problem), for example in the military. Moreover, close cooperation with government partners can legitimise the executive and, indirectly, the country’s elites.

So, if development policy contributes to autocratisation, the potential political consequences of development programmes must be given greater consideration in their objectives, planning and implementation. For example, large investments and infrastructure projects should be scrutinised to determine how they could impact local political dynamics. Feasibility and context analyses already often consider aspects like human rights, corruption or the potential for conflicts to escalate. Such questions must be directed even more specifically at political processes and power constellations: what benefit will ruling powers derive from a given investment? Answering such a question will also require discussion with dissident groups. During implementation, it must become easier to react to gradual changes, for instance through adaptive approaches.

Value-based pragmatism

Democracies cannot avoid pursuing development goals in cooperation with autocracies. When it comes to global climate and environmental protection, for example, countries like China or the Democratic Republic of the Congo play an important role. But does working with them betray democratic values? No, not if the purpose of cooperation is to promote the global common good and the role of democracy has been well considered.

Germany, which generates its common good through exports, is economically dependent on geostrategic cooperation with autocracies. Pragmatic relationships are a necessity, but democracy should not be sold out. It is important to openly declare support for democratic values and condemn their violation. Under value-based pragmatism, cooperation with strict autocracies without strategic relevance for Germany would either become of secondary importance or expire.

Some autocracies are closed, others more open

As mentioned above, autocracies are heterogeneous and offer different possibilities for cooperation. In more open autocracies that allow some degree of participation – like Burkina Faso, Ethiopia or the Philippines – there are starting points for measures that promote the common good and democracy. Opportunities are more limited in closed autocracies like Guinea, Myanmar or Turkmenistan.

From a democratic perspective, there is reason for optimism: after all, autocratisation can be a reversible process. Zambia and South Korea have proven this recently, for example. If democratic development policy wants to resist the trend towards autocratisation, however, it especially needs allies in partner countries. Seeking, finding and supporting democracy protectors therefore remains an important task for state development policy.

Why democracy?

Democracy is sometimes called into question as a goal of development policy. It is worthwhile, however, to consider democracy and sustainable development together:

- Cooperation: Sustainable development requires global cooperation. It is more likely that reliable and long-term cooperation will succeed under democracies.

- The common good: studies show that democratic regimes are more oriented towards the common good in a variety of areas and achieve better development results than autocracies, for instance, when it comes to health, social security and prosperity.

- Human dignity: When one compares different political regimes, democracies are the ones that aim to protect the dignity of all people equally – and not just on paper.

References

Leininger, J., von Schiller, A., 2023: What works in democracy support? How to fill evidence and usability gaps through evaluation. Evaluation Vol. 29/4.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/13563890231218276

Roll, M., 2021: Institutional change through development assistance. The comparative advantages of political and adaptive approaches. Bonn, DIE Discussion Paper.

https://www.idos-research.de/discussion-paper/article/institutional-change-through-development-assistance-the-comparative-advantages-of-political-and-adaptive-approaches/

V-Dem Institute, 2023: Case for Democracy Report.

https://v-dem.net/our-work/research-programs/case-for-democracy/

Julia Leininger is a political scientist. She heads the research programme “Transformation of political (dis-)order” at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) in Bonn.

julia.leininger@idos-research.de