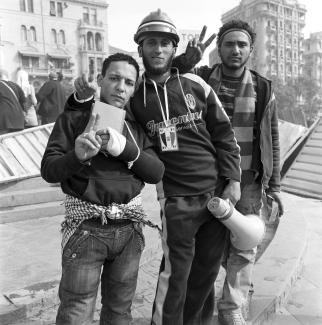

Arab spring

“Jobs are hard to find”

Is President Mohamed Mursi’s legitimacy in doubt after he grabbed extra powers in a constitutional amendment in late November, and held a controversial constitutional referendum in mid-December?

Well, he is the elected president, which obviously gives him legitimacy, and the opposition organisations in the National Salvation Front or NSF for short are wrong to cast doubt on this fact. On the other hand, his politics have made people angry. He certainly did not win new friends by acting the way he did. It was not an elegant way of consolidating his power.

Was it a coincidence that he passed his constitutional amendment, which, among other things, put him beyond judicial review, immediately after he managed to broker a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip?

No, people in Egypt don’t think so. It seems obvious that Mursi was sure Washington would not object to his new approach to domestic politics immediately after he had shown that he understood the rules of their international game and helped to promote stability. And of course, being on good terms with the USA makes it easier to accommodate Egypt’s military, and there is no doubt that Mursi has been trying to make friends with the generals. In his eyes, the ceasefire probably indicated a good moment to assert his power.

Nonetheless, protests erupted immediately after the amendment, and the referendum that followed was confusing. A huge majority of voters accepted the Islamist constitution that Mursi’s supporters among the Muslim Brothers and Salafis had drafted, but the turnout was quite low. What does that mean?

It means several things. After two years of revolutionary upheaval, many people feel tired and resigned. There has been a lot of suffering and violence. Everybody has been affected one way or another. So many simply don’t care about voting. Some people I know, however, voted for the constitution even though they do not like it. The reason was that they long for some kind of stability. Finally, the media were reporting exit polls all day long, so the result seemed clear very early on. Accordingly, voting felt irrelevant to many people, whether they were in favour of the constitution or opposed it.

Doesn’t the result prove that the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s traditional Islamist movement with a long history of being suppressed by the Mubarak regime, is the dominant political force in Egypt? And isn’t that particularly so as long as they are supported by the Salafis, more radical Islamists who are inspired by Saudi fundamentalism?

There’s no doubt that no other political force has the organisational power of the Muslim Brotherhood. They have

a presence all over the country and have been networking at the grassroots level for a long time. You must bear in mind that the new political parties that were started after the revolution have only been around for 12 or at most 18 months. They have hardly had a chance to start the hard work of organising people. Opposition forces are strong in the cities, in Cairo and Alexandria, but in the rural areas, the Muslim Brothers can probably mobilise enough people to win any election.

So they are comfortably in power?

They are in power, yes, but they are not comfortable with it. They are used to being a clandestine opposition movement, not to holding office. They know, moreover, that many people think that the Muslim Brothers were the last to get on the revolutionary train – and the first to jump off. Insecure as they feel, they are increasingly resorting to Mubarak’s methods and policies. Within the state apparatus, they are placing their people in important positions. It made headlines when they acted that way at the government-run TV station, but it is pretty obvious that the same is going on inside ministries and other state agencies. On the other hand, there is infighting within their organisation, and their relations with Salafis are tense too.

What are those tensions about?

Well, one example is that the Salafis want Egypt to be run according to Sharia law. Egyptians wouldn’t stomach that. There is a lot of confusion. Only recently, Noor, the major Salafi party, split because some leaders felt the party should do more to attract women and Copts, the Egyptian Christians. The very idea may seem weird, but it resulted in the split of Noor.

So Egypt’s Islamist forces are not about to establish a dictatorship?

They might like to do so, but at the moment they look insecure and confused. There is no sense of a strong and coherent government. But that does not mean that there is no danger of increasing authoritarianism. Intellectuals and artists do worry a lot about where all this will lead to.

And they definitely don’t feel reassured by the recent censorship of the TV comedian Ahmed Meligy and the investigations of Bassem Youssef, Reem Maged and others?

No, of course not, these cases are really quite disturbing. These are very intelligent people, and they made fun of Mursi and the Muslim Brothers – directly or indirectly – in a poignant way. Egypt never enjoyed freedom of speech, and since the Muslim Brothers don’t know how to deal with ridicule, they’re attempting to scapegoat these personalities.

In the past, you told me that the liberal and left-wing organisations were too disorganised to have much of an impact. In the meantime, many of them have joined forces in the NSF. Does that make a difference?

Only to some extent, because the NSF’s sense of unity is quite superficial. The NSF may yet become a coherent political force, but so far it is not. They agree on opposing Mursi and the various shades of Islamism, but not on much more. The real test will be the parliamentary elections that are planned for April. Will they manage to form a joint list so opposition candidates won’t get into one another’s way? And how many votes will they get? The average person in Egypt is not too fond of the Muslim Brothers these days, but not sure the NSF is a serious alternative either. This umbrella organisation is facing a lot of challenges.

What are the fault lines?

One is whether Amr Moussa, a former Mubarak minister who later fell out with him, should be part of the NSF. He joined it, but not all constituents welcomed him. Moreover, unlike the leftists, some liberal activists shy completely from demanding social justice. That is another major fault line.

What is the Muslim Brothers’ stance on social justice? They have the reputation of running many charities with good track records.

Yes, they do, but charity is not what Egypt needs. It is disappointing that the new constitution does not mention social justice. The tax system, for instance, is quite unfair. Those at the bottom pay 10 % income tax and those at the top 25 %. The top rate is very low in comparison with European countries, for instance. The rich are simply not contributing their due share. So in terms of policymaking, there is a lot to do, but the government is not rising to those challenges. And it is hard to say who is really in charge. There was a bizarre moment when several leaders of the Brotherhood made statements about tax policy, with Mursi later re-iterating those statements. It made people wonder who is pulling the strings.

The Arab spring was triggered by rising food prices and growing economic desperation, but things have not gotten better since, have they?

No, the situation is getting more difficult. The Egyptian pound is depreciating, and as the country imports many basic items, including food, prices are rising. Bread and butter issues matter to the average person more than anything else, and jobs are very hard to find. In this context, the government is behaving just like Mubarak used to. They speak of “tightening the belt”, as if people weren’t living with very tight belts already. The mood is quite dark, and people are exhausted psychologically and emotionally.

So it is impossible to tell where the country is heading?

Yes, these are tough and confusing times.

Yasser Alwan is a Cairo-based photographer.