Cyber security

There are many ways you can be scammed on the web in Africa

Local and international fraudsters are stepping up their scam games, taking advantage of increasing internet use, the proliferation of social media and the growing number of Africans with smartphones.

In September 2022, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) estimated that 40 % of Africans had access to the internet. The UN agency considered these 560 million persons to be at risk of online scams, digital extortion, business email compromise, ransomware and botnets.

Interpol, the international criminal police organisation, shares the concerns. It sees online services exposed to risks due to growing demand and “a lack of cybersecurity policies and standards”.

Many online scams are based on deception. For example, they try to get victims to pay for counterfeit products. This crime is particularly serious on a continent where many people live in poverty. Scammers also exploit the desperation that comes with this. They pose as public figures or fake the pages of large companies, advertising job opportunities that do not exist. They then fleece applicants, for example by charging “application fees”.

Covid-19 made things worse. Many people were ill, but health facilities were overburdened. Fraudsters took advantage of the situation and sold fake medicines. In view of spreading unemployment, moreover, fake visa schemes for the USA, Canada or Europe proliferated. Applicants were asked to pay a fee to obtain a work or school visa, but the scammers disappeared as soon as the money was paid.

Another problem is phishing attacks, which hack devices and data systems. Information is stolen from individuals, companies and authorities. For example, in May 2023, news reports indicated that hackers with links to China had hacked Kenya’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Finance when a government employee downloaded compromised files. In addition, they reportedly hacked into the cyberinfrastructure of Kenya’s National Intelligence Service. The impact of such crimes can be devastating on reputation, finances and security in general. There are also many cases of digital identity theft. Credit and debit card theft matters too.

Empty bank accounts

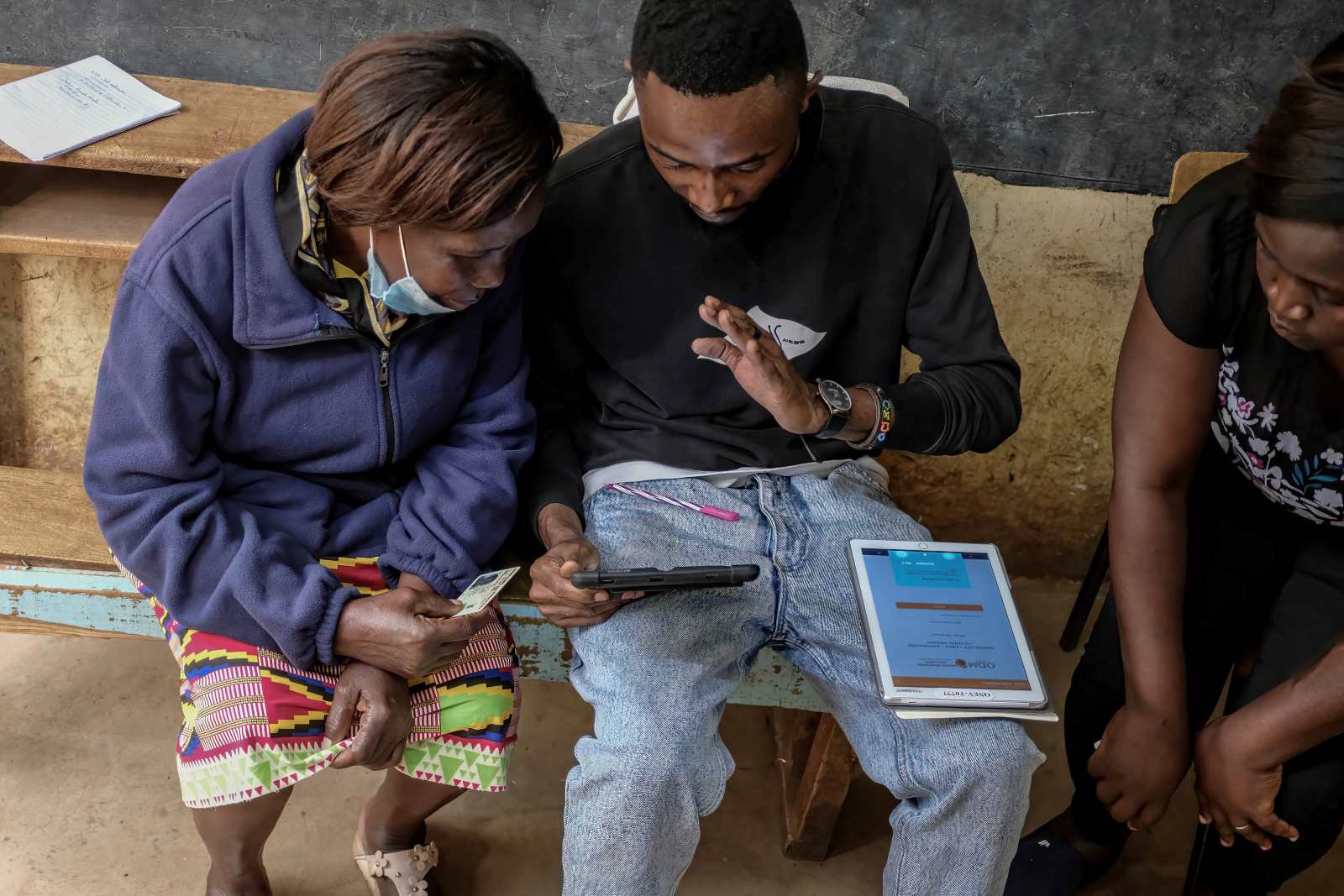

In Kenya and South Africa, digital financial fraud is very common. Usually, the scammers pretend to be calling from mobile phone companies. They ask for personal information. Once they have access to subscribers’ identity module cards, they empty the mobile phone wallets and even bank accounts, if those accounts are connected to the phone number.

Furthermore, in Kenya, suspicion is spreading that some rogue employees of mobile phone companies as well as banks are withdrawing money from customers’ accounts. Typically, the victims are elderly people who are not familiar with electronic transactions. But it is not only the elderly who fall victim. Young people are affected too.

Additionally, cryptocurrencies have become quite popular in Africa, and they offer a range of opportunities for cybercriminals. A much-used strategy is to invite people to invest in fake cryptocurrency accounts.

Digital blackmail takes many forms. Fake profiles on dating apps are used to prey on victims. People are tricked into revealing personal information and sharing compromising photos, which are then used for blackmail. Targets include public figures. Recent examples on the continent are Nigerian musician Tiwa Savage or former Kenyan governor John Lonyangapuo.

The compromise of business emails must be taken seriously too. Cybercriminals use the email accounts to hack into corporate systems and divert payments. As their networks and botnets become more sophisticated, they often no longer start with classic spam emails.

SDG achievement at risk

The widespread prevalence of digital fraud in Africa is detrimental to Africa’s young and promising e-commerce industry. It leads people to distrust online companies in the first place. No one wants to end up paying a fake online shop for a non-existent product. Many customers thus prefer in-store purchases and cash payments. They do not want to leave a digital footprint in electronic transactions, as these might become digital entry points for fraudsters.

In Africa, the debate on digital fraud is currently a tangle of the many issues revolving around data security, privacy and the governance of online platforms. On the other hand, these discussions only involve a tiny minority of technology enthusiasts, entrepreneurs and often foreign profiteers who seek to expand their businesses by entering the emerging and so far poorly regulated digital market on the continent.

It is obvious that more must happen. Indeed, the African Union (AU) is now pushing for stronger digital regulation. In recent years, it has issued a number of important papers, including the AU Data Policy Framework, the Digital Education Strategy and the Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection.

The Digital Transformation Strategy for the decade to 2030 is probably the most relevant publication. It makes clear that moving towards a digital economy is crucial for the continent’s development and the achievement of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs). It underlines that a lack of trust in digital technology will do serious damage in African countries. The strategy declares it to be essential that “African Union Member States have adequate regulation, particularly around data governance and digital platforms, to ensure that trust is preserved in the digitalisation”.

Moreover, African governments need to work towards open standards and cross-border interoperability. That is needed to inspire more digital trust. However, digital fraud exceeds African borders. Prosecuting cyber criminals requires international cooperation across multiple jurisdictions.

The continent’s major economies such as Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa have put laws and policies in place to tackle digital fraud. Too many regulations, however, only focus on financial fraud.

At the same time, a worrying development is that some governments use cyber legislation to restrict freedom of the press and of expression. In Kenya and Uganda, the courts have struck out some clauses of this kind, stating that they are unconstitutional and illegal. Other restrictive clauses have survived, jeopardising free speech in the digital public sphere.

Alphonce Shiundu is a journalist, editor and fact-checker in Kenya.

Twitter: @Shiundu