Modern society

Time constraints make democracy look dysfunctional

Technological change takes place at great speed, with serious consequences for culture, markets, law and society in general. By contrast, democratic deliberation takes a lot of time, so policymakers struggle to stay abreast. In many cases, different kinds of change confront them with unprecedented problems for which they have no ready-made solution.

It is time-consuming to draft, adopt and implement policies. First of all, a new phenomenon needs to be analysed. Only then is it possible to design measures to deal with it. Next, policymakers must choose among options and eventually convince voters of their choice’s validity. Democratic procedures indeed sometimes take so long that they do not keep up with what they are supposed to regulate.

The impacts of climate change, for example, are getting worse, and too little is being done for both mitigation and adaptation. Migration is modifying the composition of societies. At the same time, demographic change means that new needs must be taken care of. Innovative industries emerge as old ones collapse. By the time a policy is implemented, it may already be out-dated.

That is most evident in regard to digital technology. Other developments are not happening quite so fast, but the impacts are often only felt suddenly. That is the case, for example, when existing infrastructure suddenly proves inadequate in view of extreme weather events like flooding or when the telecommunications network in rural areas does not support fast internet access. In cases like that, policymakers have evidently been too slow.

Sign of the times

Hartmut Rosa is a German sociologist who argues that permanent acceleration marks our era. In his eyes, it is essentially synonymous with modernisation. Technology is an important facilitating force. In the course of industrialisation, it has sped up production, transport and communication. According to Rosa, market competition means that private-sector companies do their best to exploit any opportunity to accelerate further. Those who succeed in doing so gain a competitive advantage. Others will follow their example – or fail.

Acceleration is thus closely related to ever increasing productivity and economic growth. It means: faster, faster, faster, and it results in constant demands for more and more and more.

The quest for acceleration transcends economic growth, however. It does not stop in a recession as businesses try to become more efficient during slumps. Even when an economy is stalling, time pressures continue to increase.

One consequence of acceleration, as Rosa elaborates, is that everything in society is becoming prone to change. What feels normal today, will look outdated tomorrow. What seems cutting-edge today, will seem quaint in the not-too-distant future.

Fragile identities

Rosa points out serious psychological implications. Constant change weakens a person’s sense of identity. One can no longer trust one’s professional skills to suit tomorrow’s demand. The need to adapt increases as society becomes yet more dynamic. Learning is a constant duty and never completed.

On the other hand, no one can process the huge volume of readily accessible information fast. No person can tap – and even less fully use – every relevant source. One thus always feels a bit uninformed, unable to tell whether one’s knowledge on anything is really up to date. While we are constantly admonished to check facts, we must trust sources we cannot check completely. Some people make the superficial, but comforting choice to trust a single source that claims the authority to give simple answers to many questions.

As fewer and fewer things can be taken for granted for more than a short time, Rosa argues, many people feel alienated. When a computer programme is updated, for example, that does not only mean that users get more or better options. It also means that some of their existing knowledge is invalidated. They are expected to relearn how to use a tool they have been familiar with in daily life.

Digital alienation

According to Rosa, it is increasingly common for people to use computer programmes only according to their intuition. They shy away from the effort of acquiring the full competence again and again. Moreover, they do not have the time to keep relearning. The acceleration of society means that workloads are growing, so time pressure is exacerbated. Feeling insecure about the tools one uses is, of course, particularly disturbing when one needs to perform with ever increasing speed whilst fulfilling increasingly complex tasks. Rosa speaks of frantic standstill (“rasender Stillstand”). In an endless rat-race, everyone struggles to stay in place, but no one moves ahead anymore. The need to keep adapting to fast change is psychologically disconcerting, as Rosa points out. The promise of modernisation, according to him, was always that individuals would be empowered to take their fate into their own hands. Instead, people must keep adjusting to ever changing conditions. In Rosa’s view, the promise of modernity is thus not being fulfilled. People are not free to become who they aspire to be. They must respond flexibly to whatever innovations they encounter. Strong beliefs and personal principles are not helpful.

Identity politics

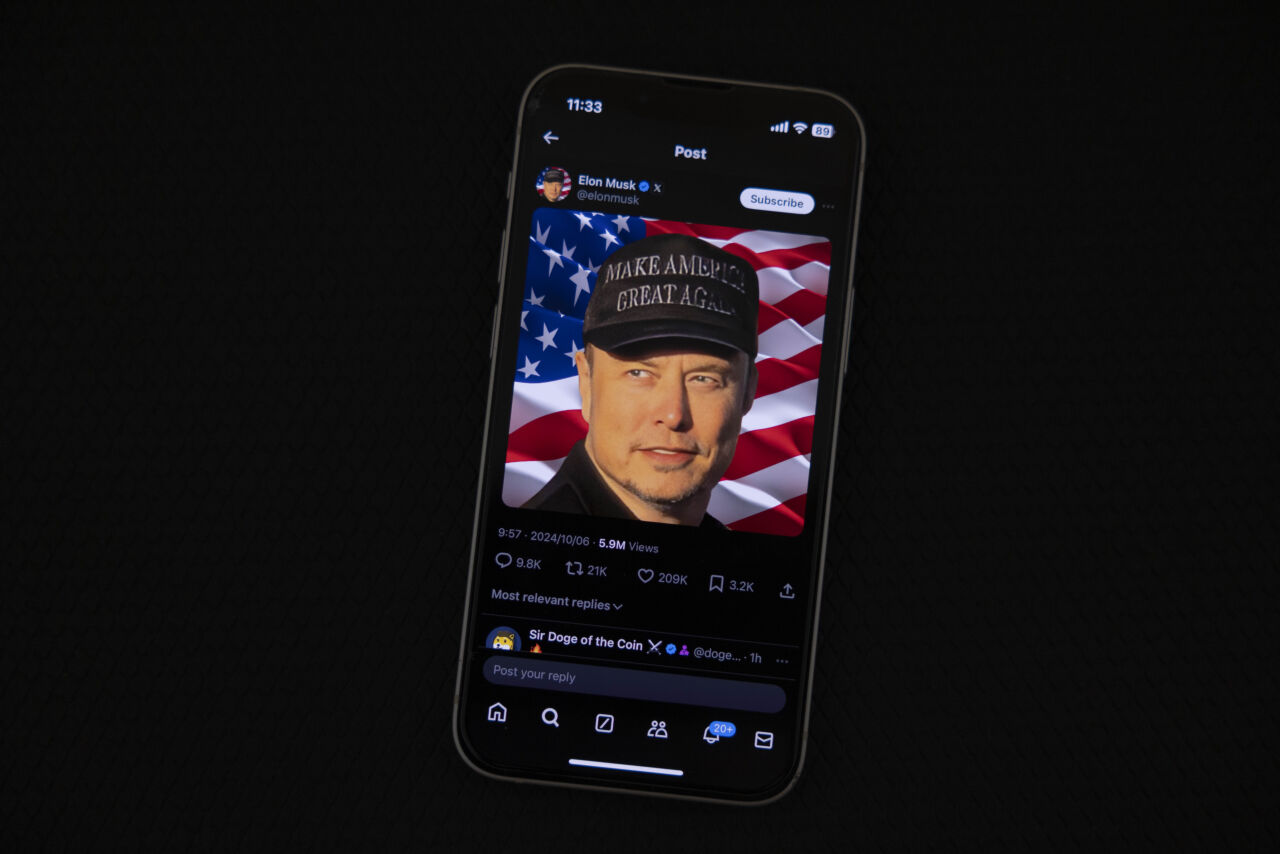

As personal identities are indeed becoming more fragile, the longing for unquestioned belonging grows stronger. Quite obviously, right-wing populists exploit the fact that identity politics resonate with masses of people.

Acceleration thus poses a double challenge to democracy. On the one hand, standard democratic procedures are too slow to stay abreast of change. On the other hand, parties with authoritarian leanings attack the democratic order arguing that it is denying “the” nation its “normal” lifestyle. Rosa does not delve deeply into the second issue, but his thinking fits in well with what Jan-Werner Müller, the political scientist, has written about populism.

Right-wing populists rarely complain about acceleration. Their standard claim is that vicious global forces are trying to exploit, hurt and even replace their people, and that “the” nation must defend itself against this kind of aggression. They pretend to be defending national homogeneity against migrant intruders as well as globalist elites. Donald Trump – the once and future US president – is the most prominent, but far from only example. Some conspiracy theorists even claim that a global elite is using migrants to replace “the” people.

This kind of misleading propaganda exploits another weakness of contemporary democracies. Nation states are unable to rise to global challenges on their own. The implication is that competent regulation requires international cooperation. These facts have gained much more public attention than the acceleration challenge. To put it another way: national sovereignty is limited not only regarding important global public goods such as international trade rules or environmental health (climate, biodiversity, desertification, plastic waste et cetera). Fighting organised crime or controlling diseases is also likely to prove futile if it is only carried out at the national level. Even macroeconomic management is beyond the control of many governments to a large extent. After all, tax levels, interest rates and sovereign debt must be internationally competitive.

Globalisation plus acceleration

All too often, elected governments feel they have very few choices. Technocratic decision making is increasingly the norm. Social needs and environmental requirements are often neglected. Dysfunction, of course, further feeds populist anger. For obvious reasons, moreover, multilateral policymaking is even more time consuming than national politics, so the global dimensions of social challenges compound the acceleration issues. Right-wing populists claim to defend the people, but they typically serve oligarchic interests. Quite often, they are funded by super-rich individuals. The background is that the latter have an interest in preventing democratic regulation, and they know that regulations passed by a single nation state will generally be toothless. In today’s interconnected world, a governments’ effectiveness often depends on its cooperation with other governments. Accordingly, that kind of cooperation – especially in the context of the EU or multilateral institutions – is disparaged as evil “globalism”.

Reference

Rosa, H., 2010: Alienation and acceleration. Natchitoches, Louisiana, NSU press.

Hans Dembowski is the editor-in-chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu