Multilateral policymaking

Involving local people in order to reach biodiversity goals

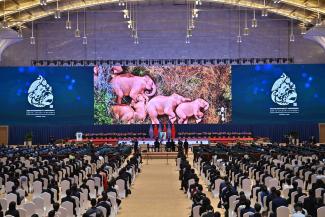

D+C/E+Z: At the biodiversity summit in Kunming-Montréal at the end of 2022, the global community agreed to put 30 % of the world’s oceans and land under protection by 2030. What will happen next?

Jochen Flasbarth: Given the geopolitical upheaval of the current moment, the conference’s success matters beyond the issue of biodiversity. In the context of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the summit proved that multilateralism can still work. Global problems require multilateral solutions.

The outcome of the conference is a specific framework of targets to be achieved by 2030. Apart from global action – consider the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund – the big issue is to implement national biodiversity strategies and plans of action. The concept resembles the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in climate protection. Germany is providing systematic support to partner countries, helping them to implement their national biodiversity plans.

You yourself made a significant contribution to the final consensus in Montréal. How did that come about?

China had the presidency and was pulling the strings accordingly. Following established procedures, the major points of contention were only tackled close to the end of the conference. At that point, so-called facilitators were tasked with finding the kind of consensus that big international conferences always need.

There was a lot of discussion about the goal of designating 30 % of all land as protected areas. Nobody disputes the importance of protected areas. What is more important, however, is to use land and oceans sustainably, in ways that promote biodiversity. The question of how we farm around the world is more urgent than whether 28 % or 32 % of a country’s territory is protected. However, the figure of 30 % had attained so much symbolic importance that the success of the conference depended on it. We thus had to deliver, which we were ultimately able to do. Other difficult issues included measures to protect genetic resources and funding.

You were a facilitator on the issue of financing, along with Jeanne d’Arc Mujawamariya, Rwanda’s minister of environment.

Yes, we already knew each other because we had worked together at climate summits earlier. People apparently knew that we get along well, which is important. It was also good that the presidency stayed in constant contact with the three teams of facilitators. Nonetheless, success came at a price.

What do you mean?

The funding needs are enormous, and it is good that we have agreed on goals:

- By 2030, at least $ 500 billion of environmentally harmful subsidies are to be phased out each year.

- At the same time, at least $ 200 billion per year is to be mobilised from public and private sources for biodiversity-related goals.

- By 2025, at least $ 20 billion and, by 2030, at least $ 30 billion are to flow annually from industrialised to developing countries as part of the overall financial requirement. That is more than Jeanne d’Arc Mujawamariya and I had proposed. Moreover, we did not propose a goal for 2025 – the presidency did so.

Why didn’t you?

Given the generally tight state of public finances, we saw that the classic donor countries would not be able to raise their budgets for international biodiversity protection to this extent in the coming years. When you know that even the best intentions will hardly secure the funding, these fixed figures may become an enormous liability for further cooperation. They may damage trust.

There was also debate about whether the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund should become an independent institution or be hosted by an existing one. We facilitators wanted to affiliate it with the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which has a governance structure that takes into account the concerns of developing countries and is not dominated by the west. We got agreement on that score.

What were developing countries’ concerns?

Just like industrialised countries, developing countries are not a monolithic block with unified positions. To some, an independent structure that would provide equal representation for developing countries was important. However, there were tactical interests as well. Some Latin American countries vehemently called for an independent fund, with the true aim of driving up payments.

From the point of view of the BMZ and other donor institutions, affiliating the fund with the GEF would make it more efficient and effective. New funds have no guarantee of succeeding. Plugging into existing structures generates less bureaucracy, thereby improving access especially for countries with weak capacities.

Is there a basic formula for successfully concluding multilateral negotiations?

There is no “one size fits all” solution. First of all, it is necessary to firmly believe that international negotiations do lead to a certain degree of commitment. The decisions from Kunming-Montréal send a strong signal in terms of both policy and international law. But success also depends on many other things. In the final phase, it is important to have actors who understand parties’ mutual interests. That is the role of the facilitators in particular. It is imperative that they subordinate some of their own national interests in order to propose a globally accepted solution. The goal is to reasonably balance the interests of all participants.

How do the interests of countries with high, middle and low incomes differ?

Every country’s interests depend on a variety of factors. The least developed countries (LDCs) want as much direct and uncomplicated financial support as possible. The situation is more complicated in emerging markets. Brazil’s current government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, for example, is demanding more international support for forest and climate protection. On the other hand, the Democratic Republic of the Congo wants to be compensated for not using resources the way industrialised countries did in the past. That is a very complicated discussion, and one must consider very carefully whether you want to go down that road. Another interesting case is Costa Rica, where reforestation has become a particularly successful model. Costa Rica is playing a positive, mediating role.

Does success also depend on civil society?

There is a strong community of non-governmental organisations in the field of biodiversity and conservation. It is not entirely unified, but it acts in concert on important issues. There are also non-governmental organisations that advocate for the interests of indigenous peoples. To a certain extent, indigenous rights and nature conservation go hand in hand. Some indigenous organisations also worry, however, that global conservation will be carried out at their expense in the areas where they live. Ultimately local people must generally be included in local efforts. Those who want to expand protected areas must also cultivate acceptance so that biodiversity goals can really be achieved.

To what extent does Germany’s future depend on conservation in distant parts of the world?

The future of not just Germany but of all countries depends on it because global environmental crises feed off each other. If we don’t make progress on protecting biodiversity, we will also fail to reach the 1.5-degree climate goal. We will make progress on climate mitigation if we protect and manage forests, moors and oceans in ways that make them absorb and bind CO2. Unfortunately, the reverse is also true. Global warming is changing ecosystems and accelerating the loss of biodiversity.

Is there a specific developmental perspective on biodiversity?

It takes many forms. For example: ecosystem protection can make an enormous contribution to creating local jobs. In projects like reforestation, rewetting moors and restoring mangroves or river systems, there is enormous potential for creating jobs in the short, medium and long term. In that way, protecting biodiversity can also help generate sources of income.

Jochen Flasbarth is the state secretary of Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

https://www.bmz.de