Islamist ideologies

Fundamentally different fundamentalists

This article was first published on 10 December 2024 and updated on 30 January 2025.

In early December, Syrian rebels took Damascus, forcing the brutal dictator Bashar al-Assad to flee to Moscow. It is too early to tell whether this was the beginning of the end of the country’s long civil war. Violence seems to keep flaring up between Kurdish militias and pro-Turkish forces.

At this point, Ahmed al-Sharaa – also known as Abu Mohammad al-Jolani – seems to be the most powerful man in the country. He has been appointed interim president and leads the Sunni militia Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which is the strongest rebel group. It has roots in Al-Qaida and ISIS, but later split from their version of global jihadist terrorism. Al-Sharaa now endorses a kind of Syrian nationalism that appears to tolerate the countries’ diversity of communities, including non-Muslim religious faiths. Over the years, HTS has cautiously built ties to Turkey, though cooperation was difficult, at least initially. What kind of political system will now emerge in Syria is an open question. Whether HTS embraces democracy is not clear.

The country’s long years of strife, however, show just how complex Islamist ideologies are. There actually are three different ideological traditions that emerged in different countries and served different political interests. The different traditions are often more likely to fight one another than to cooperate. All three branches of Islamism are relevant in Syria.

The three different approaches to Islam-based fundamentalism are:

- The Muslim Brotherhood, which was launched in the 1920s in Egypt in response to British imperialism,

- Wahhabi puritanism, which is related to the Royal House of Saud and other Gulf monarchies, and

- Shia fundamentalism, which is linked to Iran’s theocratic regime.

None of them are internally fully coherent or politically consistent over time. In this sense, they are not fundamentalist in a monolithic sense. Like all political ideologies, they adapt to changing circumstances in a variety of ways.

Muslim brothers

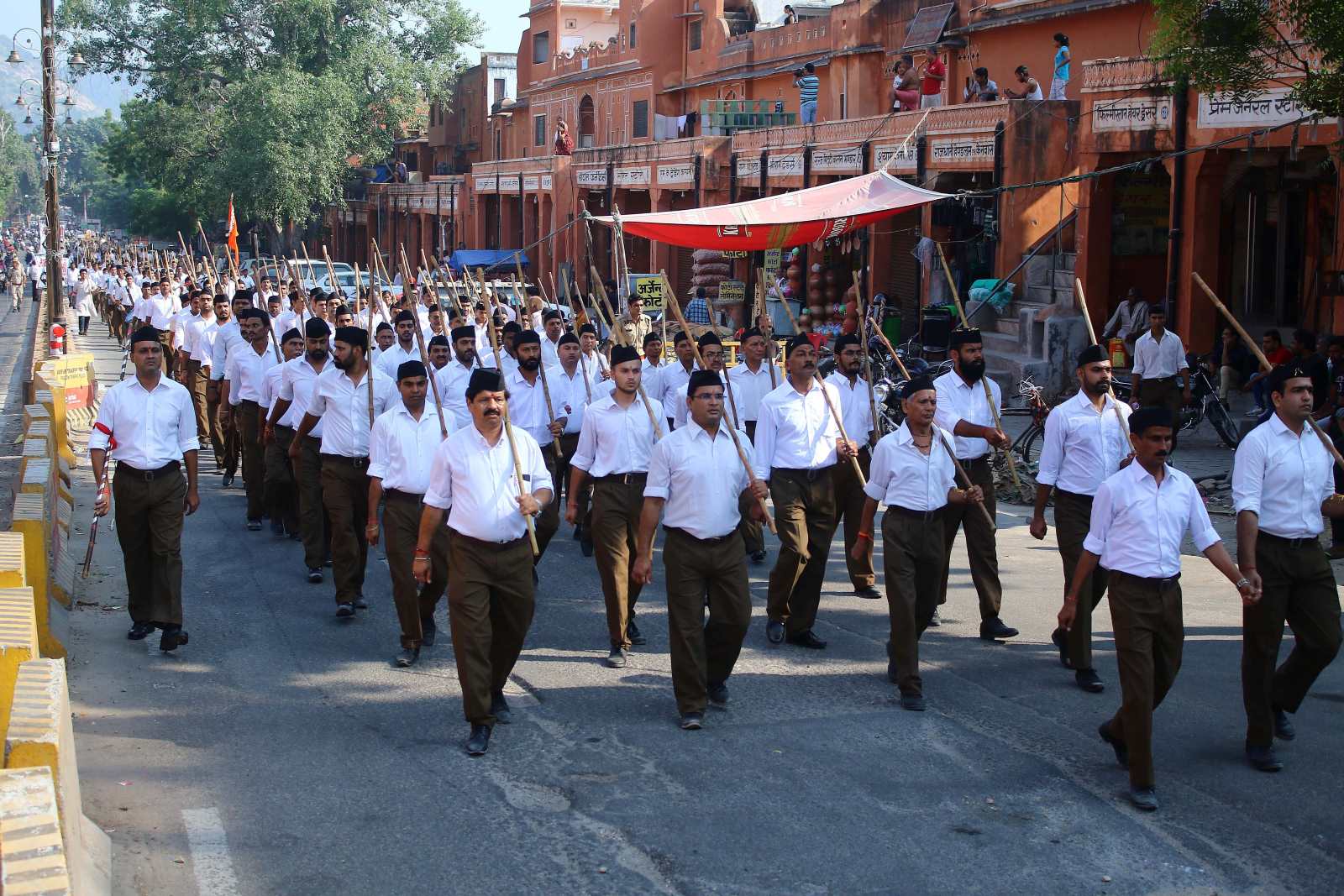

The Muslim Brotherhood is perhaps the most modern of the three. In some ways, it resembles the Hindu supremacist RSS in India. Both were initially based on educated middle-class people who were appalled by the corruption of the colonial power. The idea was that only the purity of religion could ensure integrity. Doctors, pharmacists, lawyers and other privileged colonial subjects yearned to see the unjust rule of foreigners replaced with a more just order run by the faithful, though not necessarily faith leaders.

A big difference between the Muslim Brotherhood and India’s Hindu supremacists was that the latter had a narrow-minded identity agenda from the start. To some extent, they were more interested in oppressing the subcontinent’s Muslim minority than in ending colonial rule. On the other hand, leaders of India’s Muslim community insisted that their people would need a separate state after independence so they would not be at the mercy of Hindus. Their ideology, however, was not Islamist. They claimed to represent the Indian subcontinents’ Muslims, but they were not driven by notions of returning to original Koranic values.

Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood had a political agenda, but it also had a welfare agenda. It was involved in charitable action and educational efforts. To a considerable extent, these programmes served to win the trust of grassroots communities. At the same time, the Muslim Brothers mostly worked in a clandestine manner. Fearing repression, they organised in secret networks.

The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood was copied in other Arab countries on the Eastern and Southern shores of the Mediterranean as well as in Turkey. Typically, these groups remained repressed opposition forces. After independence, the new leaders of Arab countries promoted a secular understanding of nationalism, and so did Turkey’s leaders after the collapse of the Ottoman empire. In those leaders’ eyes, religion was an outdated obstacle to modernisation. The regimes were authoritarian, and Muslim Brother activists often ended up behind bars.

Their clandestine networks survived, however, and so did their ideology. Today, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his party AKP are rooted in the Muslim Brother tradition. Erdoğan’s attitudes have become increasingly authoritarian in the past decade, but he was once a modernising reformer. One might say that he dismantled Turkey’s old deep state before establishing a new deep state. Disappointment in the EU accession process was certainly one reason he backed off from western policymakers.

Another Muslim Brother was Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s elected president for a brief period after the Arab Spring. He was toppled by the military, and his political movement is once again oppressed.

Tunisia’s Rached al-Ghannouchi also belongs to this tradition. Like Morsi, he became quite influential in his country after the Arab Spring, but under the increasingly authoritarian rule of President Kais Saied, he was sentenced to a prison term for corruption in early 2024. His Ennahda Party, however, had evolved to a point where it aspired to a role of Muslim Democrats akin to Christian Democrats in Germany, formally endorsing multi-party democracy.

Such rhetoric probably seems strange to many Europeans because they think that democracy and Islam cannot be reconciled. Al-Ghannouchi’s stance is much more plausible than they realise. Indeed, Ennahda’s version of the Muslim Brotherhood did resemble European Christian Democrats in important ways.

After World War II, the Christian Democrats were based on upper middle-class leaders who endorsed Catholic values in view of the Nazi dictatorship and the mayhem of the war. While Catholic church doctrine and hierarchy remain undemocratic even today, the political parties it inspired became pillars of democracy not only in Germany, but in several West European countries.

On the other hand, the tradition of the Muslim Brotherhood does not necessarily accept a multi-party system. It can turn quite authoritarian. The prime example is Hamas in Palestine which runs a terrorist militia. Its militancy, however, is not typical of Muslim Brothers in general. While there is a long history of various governments calling the Muslim Brothers terrorists, many of the organisations suffered more violence than they perpetrated. In Syria, Hafez al-Assad, the father of Bashar and previous dictator, brutally suppressed Muslim Brother activity. His forces killed at least 10,000 people in a three-week massacre in Hama in February 1982. According to some estimates, there were even 40,000 dead. Today, Syrian militias that are directly supported by Turkey basically belong in this ideological camp.

Wahhabism

The history of Wahhabism is entirely different. This puritanical theology was adopted by monarchical clan leaders on the Arab peninsula. They wanted to establish kingdoms and longed for international respect, but their desert region and its people were considered to be backward. Responding to the condescension, not only of the west, but of Arab metropolitan centres like Cairo, Damascus or Tunis, the Royal House of Saud took to praising its role as a guardian of the holy city of Mecca. It promoted a particularly rigid version of Islam.

Oil exports, of course, helped the Gulf monarchies to increase their international relevance. They gained considerable financial clout and spent some of that money on Wahhabi missionaries. These missionaries spread their puritanical ideas in other predominantly Muslim countries. Thanks to their ability to mobilise funding for new mosques and Koran schools, they became quite influential in many places, in sub-Saharan Africa as well as South and South-East Asia. Traditional Sufism, which had focused on spirituality and was generally quite tolerant, therefore came under increasing pressure.

In spite of their alliance with the USA and western nations, the absolutist Gulf monarchies were never interested in democracy, and they remain quite despotic. Nonetheless, they lost control of the most radical versions of Wahhabi ideology, which spawned the terrorist organisations Al-Qaida and ISIS.

Afghanistan’s Taliban, moreover, have also thrived on Wahhabi support. They are perhaps the best example of how destructive this world view can become. After the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1980, Saudi-backed missionaries became active in refugee camps in Pakistan. The Taliban emerged from those camps and were actually encouraged by US agencies to return home and fight the Soviet troops. After long years of bloodshed, they took control of the country in the late 1990s and then offered Al-Qaida a safe haven. The terror attacks of 11 September 2001 made evident how badly US support for Islamist rebels in the 1980s had gone wrong.

It is actually not difficult to tell Wahhabi-inspired Islamists’ from the Muslim Brothers’ variety. The latter’s leaders typically dress like western policymakers, the former wear traditional clothing. Alliances between them are rare. Muslim Brothers generally do not accept Saudi claims to faith leadership. They also have no systematic interest in monarchy.

The Saudis therefore resent the Muslim Brothers. In Egypt, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has indeed been relying on Saudi and Wahhabi support since staging a military coup against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013. In the course of the coup, several hundred Morsi supporters were killed in the brutal Rabaa massacre. Turkish President Erdoğan regularly refers to it, in a clear display of identifying with Morsi’s tradition of Islamism. Among NATO leaders, Erdoğan is probably the one who most vehemently resents Saudi Arabia.

In Syria, Wahhabi-inspired jihadism was strongest when ISIS controlled a large part of the country about a decade ago. ISIS was degraded with international support in the civil war, but not crushed entirely. The now dominant HTS belonged in this camp but has disowned its former role models. That shows that even very radical ideologies do not necessarily persist unchanged over time.

Shia theocracy

Shia fundamentalism became an important force in global affairs in 1979 when a public uprising ended the rule of the Shah in Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile in Paris. He succeeded in establishing the totalitarian theocracy that still holds the country in its grip. But the regime has internal divisions. Policies have changed several times under elected presidents, who, however, must accept the dominance of the supreme religious leader.

The Shia/Sunni divide is centuries old. It emerged soon after prophet Muhammad had written the Koran in the seventh century. His faith had united Arabs and enabled them to fast create a new empire that stretched from the Arab peninsula to the Mediterranean coast. Nonetheless, the new religion suffered a bloody schism near its heartland. Unlike Sunnis, Shias have a formal clergy with a binding hierarchy.

In the 16th to 18th centuries, what is now Iran was the Shia empire of the Safavids. The Ottoman empire to its west and the Mugal empire to its east were both Sunni. The culture of Iran is marked by this legacy. Iran’s mullahs have skilfully used the faith to entrench their power.

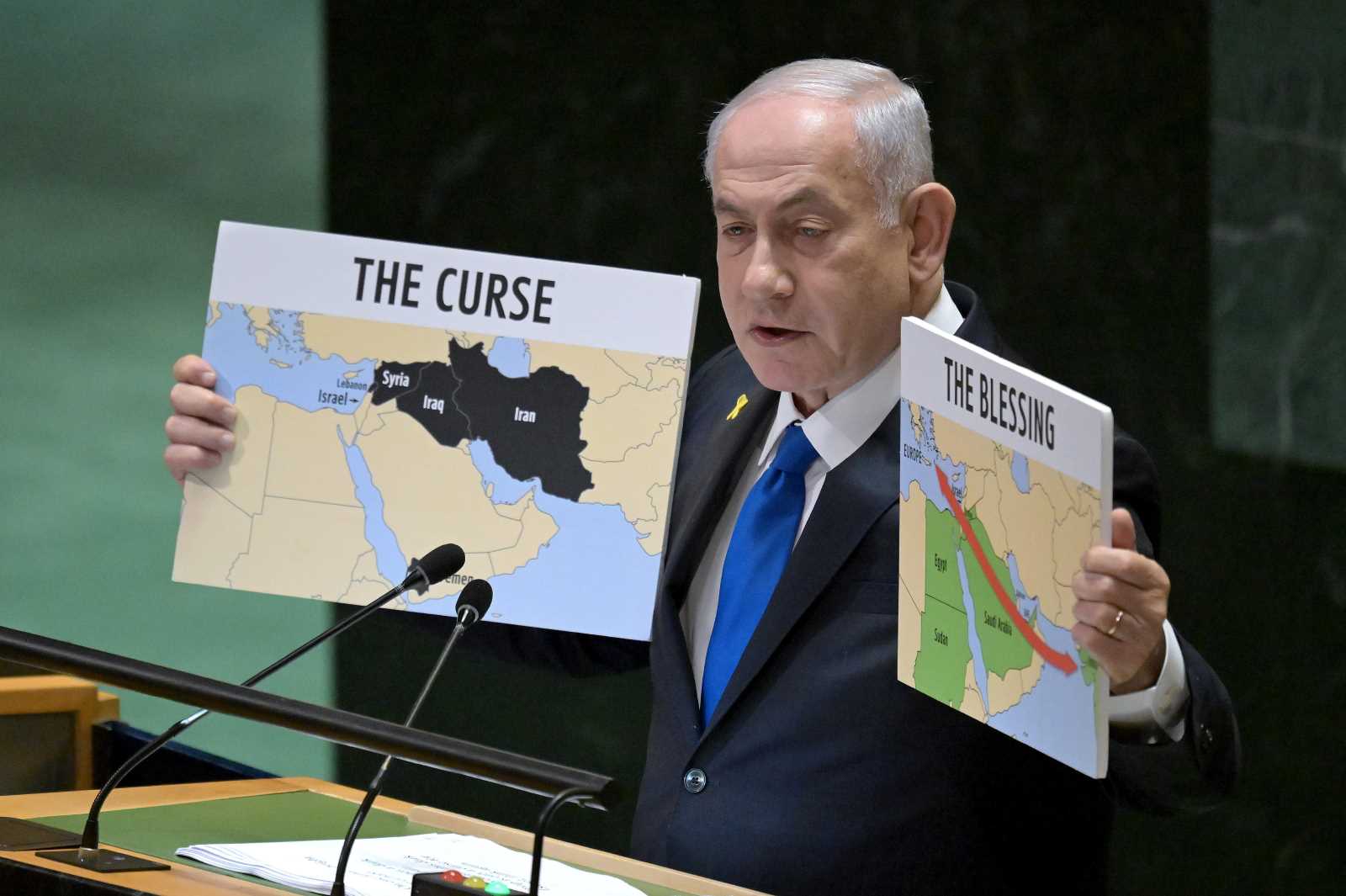

In recent decades, Tehran has been funding Shia militias across the region, including most prominently Hezbollah in Lebanon. In Syria, both Hezbollah and Iran long propped up the Assad regime. Assad’s fall is closely linked to the fact that Israel’s military has weakened not only Hezbollah, but Iran too. The Assads ran out of support from neighbouring countries. It mattered, of course, that the Assads adhere to Alawism, a small Arab community of Shias. Fear of Sunni revenge was one reason why the Assads were so atrocious in their repression of other groups.

The leaders in Tehran have been using aggressive anti-Zionist rhetoric for many years. To what extent they really want to go to war with Israel is unclear. What is obvious is that the Shia regime’s stance helps it to challenge governments of predominantly Sunni countries. It accuses them of having betrayed the pan-Islamic cause of liberating Palestinians.

Barely bridgeable divides

In this complicated setting, Hamas is the only organisation of either kind of Sunni Islamism that cooperates closely with Iran. Some observers even call it a subsidiary of Iran. However, Hamas quite clearly launched its atrocious terror attacks on Israel on 7 October 2023 without approval from Tehran. Most likely the Sunni militia hoped to start a large regional war, involving Iran. So far, the theocracy has made efforts to avoid that war.

It is safe to say that the divides between the three traditions of Islamism are barely bridgeable. Peace in Syria now hinges on whether HTS, as the currently dominant force, proves capable of uniting the country. The mutual sense of hostility is quite strong, not only among different kinds of Islamist groups, but also between Muslims and other religious communities likes Druzes and Christians. If the HTS manages Syria well, the country might become a hub of cooperation.

So far, Qatar was the centre of whatever interaction took place between the three different Islamist traditions. The background is that the al-Thanis, Qatar’s Royal family, must cooperate with Iran because the two countries share gas fields they are both exploiting in the Persian Gulf. This is an important reason why Qatar refuses to simply follow the Saudi lead of stringent opposition to Iran.

Another one is that the al-Thanis claim a role of their own on the world stage. In this context, it makes sense to reach out to Muslim Brothers and even hosting expat Hamas leaders in Doha. The al-Thani’s, moreover, do not want Qatar’s highly influential Al-Jazeera TV programme to resonate only among Wahhabi-inspired communities. They are interested in global relevance.

Hans Dembowski is the former editor-in-chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu