Comment

The black-market economics of drugs

[ By Hans Dembowski ]

So far, the international public regards Afghanistan and Colombia as the countries mainly affected by the drugs economy. According to the conventional wisdom, warlords and militias are benefiting from illegitimate crops, and the forces of law and order should finally root them out.

If only it were that simple. It is widely neglected that drug traffickers are also destabilising neighbouring countries and entire transit regions. Reports of drugs-related crime abound in Mexico and the Caribbean, and recently even in Western Africa. Addiction and trafficking are said to be wide-spread in much of Central Asia, Pakistan and Iran. Side-effects are HIV/AIDS, undermined governance and mass misery.

It would be wrong to consider these problems local, they are global. Indeed, some argue that the international drugs trade is one of globalisation’s darkest sides: a worldwide industry, driven not least by consumer demand in rich countries. The business is illegal, but highly profitable. Many of those involved lack any other livelihood – and definitely have no alternative anywhere as lucrative.

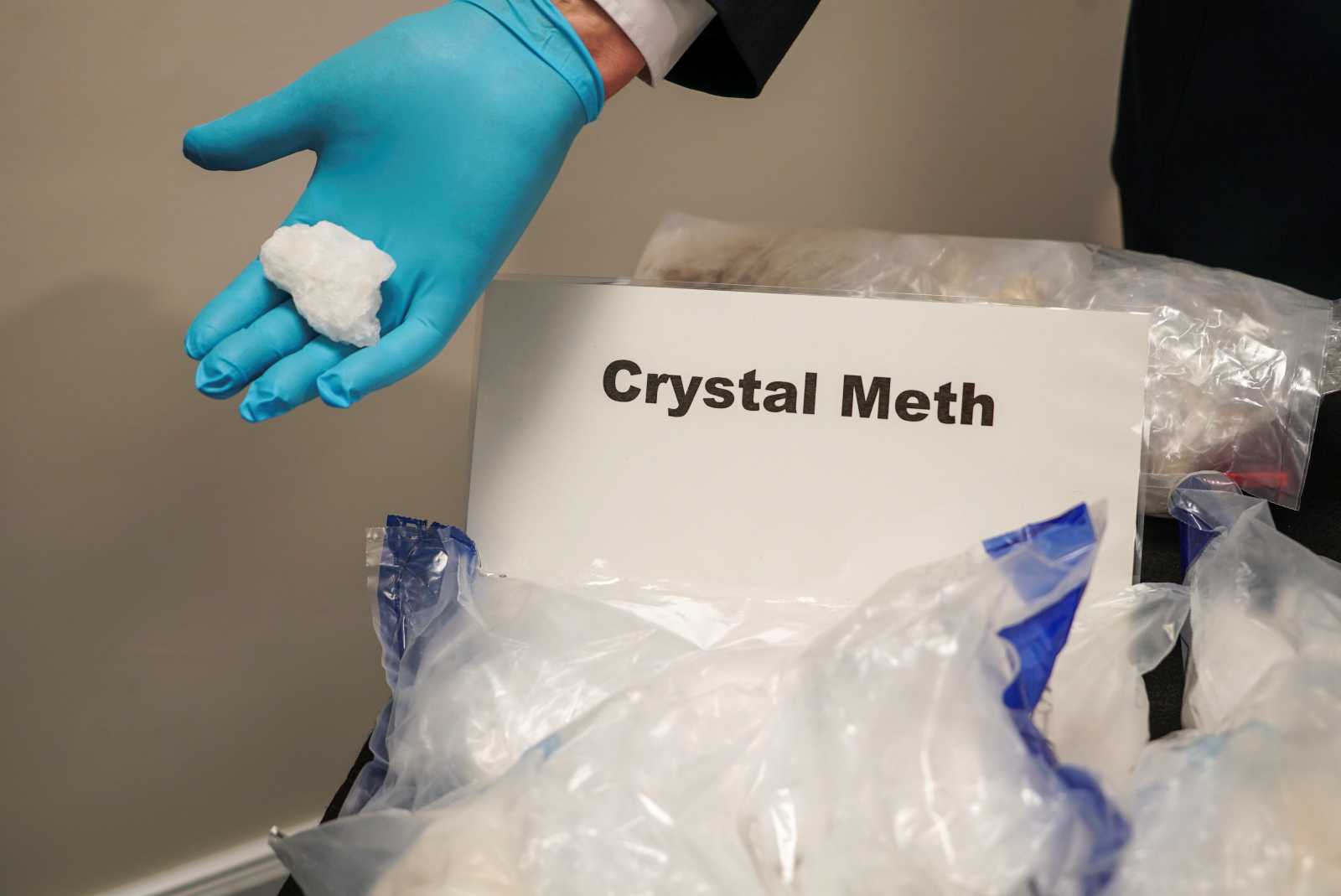

Keeping drugs illegal, however, does not solve, but rather compounds problems. Margins are highest in black markets, which, by definition, are untransparent and lack public oversight. Moreover, whoever is involved in this business has an incentive to get customers addicted – a cynical way of safeguarding demand. The cartels involved will thus systematically focus on the most dangerous drugs. Substances are manipulated, making them cheaper to produce and more dangerous to use. Moreover, the cartells always have the cash to buy arms and hire thugs to protect themselves.

Impoverished junkies, in turn, resort to theft, burglary and other crimes to fund their addiction. Those that turn to prostitution are not only exposed to sexually-transmitted diseases, but also likely to spread them.

The economics of the matter is obvious – and that is why one sometimes reads demands for more liberal drug policies in right-leaning business papers like the Wall Street Journal or the Economist. Politics, however, is more complex. The public, for good reason, abhors drugs. Any politician to speak up for legalisation will seem irresponsible, even reckless. Consequently, there is hardly any movement on the matter in national parliaments, in spite of mounting evidence of things not going well.

In the USA, the authorities have been waging a “war on drugs” for decades. But in spite of zero-tolerance approaches, it is obvious that the war is far from won. In Europe, many countries have embarked on quiet decriminalisation. Germany is an example. Small-scale consumers are largely left in peace, because municipal administrations, the police and courts want to reduce the side-effects of the drugs market. As a result, there is little publicly visible disturbance in major urban centres.

But let’s not forget that we are discussing a global problem. What is most important, is that Afghanistan and Colombia find peace, and that transit countries are not dragged further down into the destructive dynamics of the narcotrade.

Sadly, the opposite is the case, as became evident in the latest world report by UNOCD, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. In comparison, it hardly matters that UNOCD also sees consumption in rich countries stabilising and even somewhat declining – with the important exception of cocaine in Europe.

Elected governments are unlikely to move, unless they feel public pressure. Mainstream civil-society organisations must begin to address this issue, otherwise little will happen. And there is no need to advocate for legalising substances like heroin or cocaine, and making them available at supermarkets. Medical prescriptions for addicts could be helpful, at least that approach would reduce the black-market demand for heroin, 90 % of which is based on Afghanistan-grown poppies.