Genocide aftermath

Gukurahundi: Zimbabwe’s lingering genocide wounds

Nearly four decades ago, Ben Moyo, who was 24 years old and a trainee teacher in Zimbabwe’s Matabeleland North Province, experienced a sad turn of destiny when a deadly genocide erupted in the country.

The genocide left Moyo in a wheelchair. He was one of the victims of many roadblocks mounted by marauding soldiers that randomly killed villagers in Tsholotsho where he worked. On that fateful day, he barely escaped death.

The genocide came to be known as “Gukurahundi,” and raged on from 1982 onwards. Elements within the Zimbabwean army targeted the minority Ndebele tribe. Gukurahundi is a term drawn from the Shona language which loosely translates to “the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains.”

Moyo, who is a Ndebele-speaking native from Plumtree, a town on the border between Zimbabwe and Botswana in Matabeleland South Province, was beaten up by the soldiers for failing to speak in Shona. The Shona people and language dominate most parts of Zimbabwe.

“I was beaten up at a roadblock mounted by the soldiers. I dislocated my spine and thereafter developed chronic back pain.” Years later, he still suffers. “The trauma is not gone. Apart from the chronic pain, I remember my colleagues who were killed during the genocide,” Moyo said.

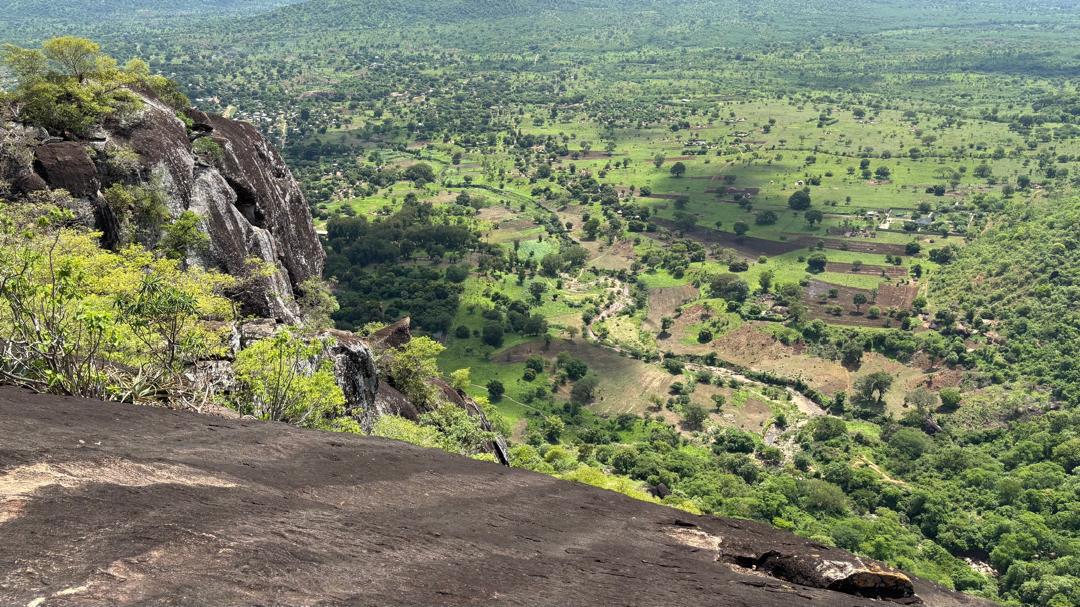

After the Tsholotsho encounter, Moyo moved to Kezi, a village in the Matobo district in Matabeleland South province where he found a teaching position. This relocation did not bring any reprieve for him as he continued to witness more genocide horrors. A concentration camp was set-up nearby, in Balagwe, where many Ndebele people were rounded up and killed in masses.

Many more people recount the horrors of the genocide. Unrelated to Moyo despite the similarity in surnames, 79-year-old Sawudeni Moyo, who lives in Tsholotsho, also suffered during the past.

“We see the hot sun. This year people will be killed by hunger,” Sawudeni said as he expressed his sadness at the ongoing El Nino drought in Zimbabwe. But to him, this cannot surpass what many like him went through during the 1980s’ genocide. “I suffered during Gukurahundi. My right hand and cheek were broken. I am disabled now. I am not afraid to speak about Gukurahundi because I was persecuted then. If someone is talking about Gukurahundi, it is something that is so painful,” Sawudeni said.

Gukurahundi was stopped by the signing of the Unity Accord in 1987 between then prime minister Robert Mugabe and nemesis Joshua Nkomo, who headed a Ndebele-dominated opposition political party known as the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU).

Fuzwayo, a coordinator for a pressure group known as Ibhetshu Likazulu, based in Bulawayo, says “the Gukurahundi victims are suffering in different ways and forms. Some of them can’t access medication because of the economic situation. Others wish to know where their relatives were taken to so that they can bury them. These are the challenges that our people are going through.”

Mbonisi Gumbo, an interim secretary for information and publicity in the Mthwakazi Republic Party that has over the years been pushing for the restoration of the historical Ndebele State, blames the state for inaction. “Many who were injured, raped or witnessed their parents, brothers and or close relatives being killed, were never counselled and had their property, forcibly seized by the fifth brigade army, replaced,” he says.

Zimbabwean president Emmerson Mnangagwa has expressed commitment to address the Gukurahundi issue to forge national unity.

Jeffrey Moyo is a journalist based in Harare.

moyojeffrey@gmail.com