Books

Moving forward without losing sight of one’s roots

This is the fourth item in our 2026 culture special with reviews of artists' works with developmental relevance.

Aya Cissoko was crowned World Amateur Champion in French boxing in 1999 and 2003, as well as in English boxing in 2006 before a serious cervical spine injury forces her to abandon her career in boxing. Displaying steely determination and enormous perseverance, she gets back on her feet, studies political science and has since published several books with an autobiographical flavour.

She is born in Paris in 1978; her parents are from a village in Mali. In her first book “danbé”, co-authored with youth fiction writer Marie Desplechin and published in 2011, she describes her family’s history, her childhood and adolescence in the banlieues of Paris, and how she gets into boxing. “Danbé”, meaning “dignity”, is a word from the language of the Malinké ethnic group in West Africa.

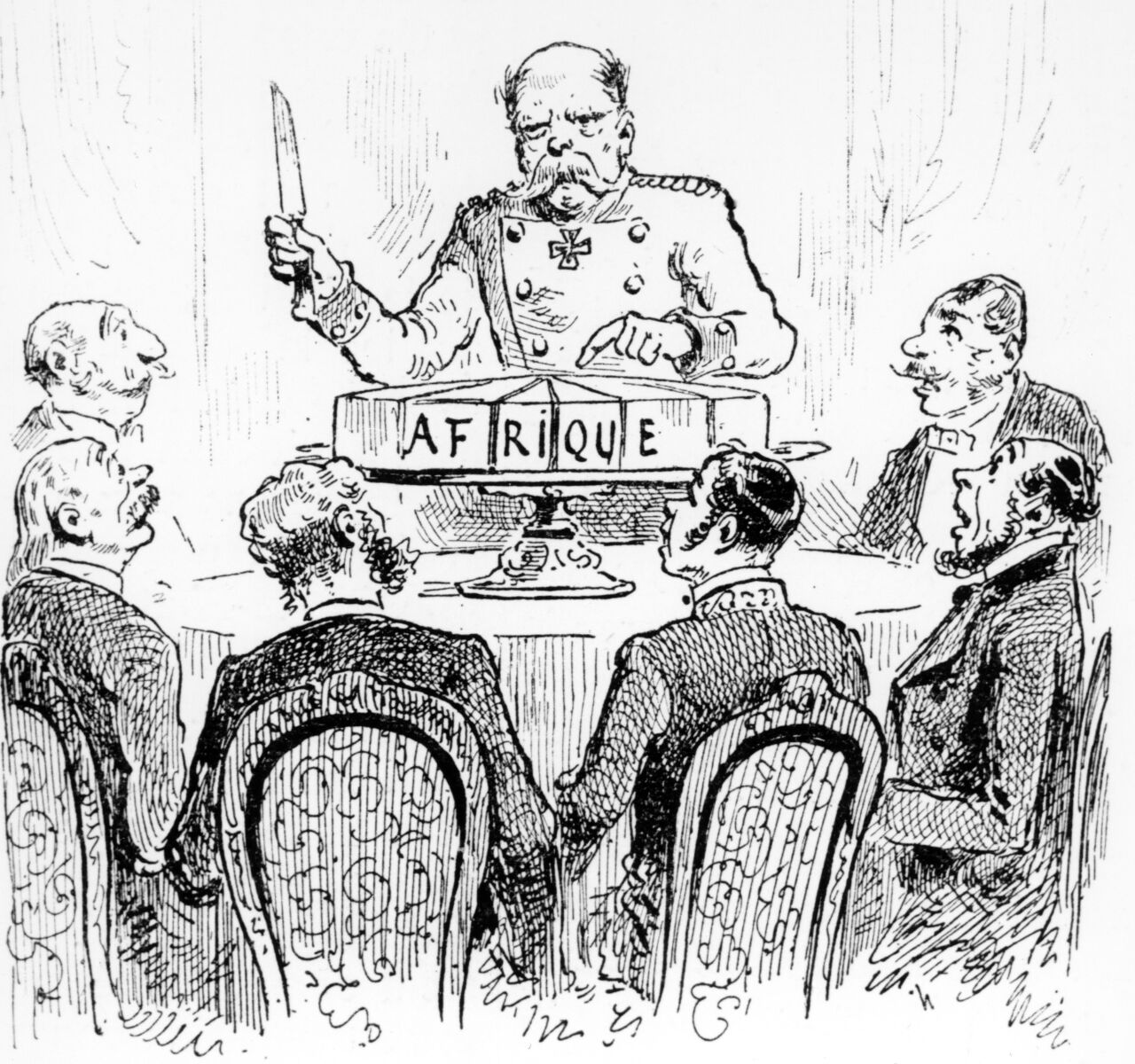

Her uncle’s decision in the 1960s to leave Mali in search of better earning opportunities in France plays a crucial role in determining Aya Cissoko’s life path. It’s a time when France is sourcing the labour it so desperately needs from its former colonies – including from the Kayes region in Mali, where the earth at the time is too dry to feed everyone, as the author writes.

When her uncle returns to Mali in the early 1970s, Aya Cissoko’s father assumes his identity, wishing in turn to try his luck in France and follow in his brother’s footsteps there. Among the places he works, under his brother’s name, is Renault, where nobody really seems to care that a different person with the same name has returned to the factory. The company appears more interested in the worker than in the human being, which according to Aya Cissoko is true both of French employers and large Malian families.

Victims of arson

Aya Cissoko’s father settles in France and marries a 15-year-old illiterate girl from his home village who follows him to Paris. Although the Cissoko family is poor, the author portrays a sheltered childhood full of gentle kindness in the banlieue Les Amandiers. This changes abruptly during the night of 27 to 28 November 1986, when the family is roused from their sleep by a fire in the building. Aya loses her father and her sister in the arson attack – one of several in Paris targeting buildings in which migrant families live. In all, 24 people die that night. The arsonists are never caught. As Aya Cissoko writes, the family was the victim of a crime that went unpunished. She is convinced that the building was set on fire with a deliberate intention to kill.

Her mother Massiré takes a conscious decision to resist the pressure from her extended Malian family, who are urging her to return to Mali. She wants to give her remaining three children the chance to achieve success in the country where they were born and go to school – in France. However, the traditional rules observed by the extended family do not permit a Malian woman to raise her children on her own. Massiré is abandoned by the Malian community in Paris. The small family is left to fend for itself, with illiterate Massiré becoming its head.

Moving to the ghetto

Along with her mother and siblings, Aya Cissoko is housed in a council flat in the notorious Cité du 140 Rue de Ménilmontant – a neighbourhood that very much has its own rules. There has been a lot of death here, writes Aya Cissoko – by overdose, suicide or murder. She talks of the 140 being her mental prison, rebels against her strict mother and feels desperate and lonely.

Out of sheer misery, Aya Cissoko takes up boxing. The sport teaches her to respect her own body, though also to respect others. It helps her channel her rage. More and more, she comes to find refuge in boxing.

Her relationship with her mother is fraught, however. While she herself sees things through the eyes of a young Frenchwoman, Massiré views them from the perspective of a Malian woman. As far as Aya Cissoko is concerned, her mother is oppressed and exploited by their Malian relatives, who are once again seeking increasingly to impose their rules on the small family. Aya Cissoko writes that her mother has retained her identity as a Malian woman.

Aya Cissoko’s novel “n’ba” (meaning “my mother”) is published in 2016. A tribute to her mother, who died in 2014, it is a tale of immigration and the female search for identity between cultures. It can teach us a great deal about how West African women in France cope with their everyday lives and integrate into society without losing sight of their roots.

Aya Cissoko details how Massiré rebels against traditional expectations following the death of her husband and refuses to accept the oppression of women. She sees her mother as having advanced Malian culture without breaking with it; Cissoko stresses that it is possible for a woman to be French and Malian at the same time.

Knowing your own story

In 2022, Aya Cissoko’s book “Au nom de tous le tiens” (meaning “on behalf of all yours”) appears. In it, she engages with her African-French identity. The book is also a kind of legacy to her daughter. Without your story you are like an empty shell, she writes, explaining how her daughter embodies a number of different stories: the story of her Malian forebears, but also the story of the Holocaust, from which the ancestors of her father, an Ashkenazi Jew from Ukraine, had to flee.

In her books, Aya Cissoko repeatedly holds a mirror up to France, a country of immigration and the place of her birth. As a boxer she competed for France and was proud to achieve victory for the red, white and blue flag. At the same time, she always felt that she was not allowed to belong entirely to her own country. All of France’s structural racism is concentrated in the story of her family, she writes, criticising institutions and those who represent them: cheap workers who were once useful for rebuilding the country after the war are now perceived as a burden.

If one reads all three of Aya Cissoko’s books, some stories repeat themselves, though often from a somewhat different perspective. This does not detract from the reading experience, however – on the contrary, all three works are to be recommended: every page opens up new opportunities to delve more deeply into the fascinating stories of this cultural border crosser.

Books

Cissoko, A., Desplechin, M., 2011: Danbé. Éditions Calmann-Lévy.

(French version. Bourlem Guerdjou adapted the book for the screen under the title “Danbé, la tête haute”; trailer with English subtitles.)

Cissoko, A., 2016: n’ba. Ma mère. Editions Calmann-Lévy. (French version; also published in German in 2017 under the title “Ma”.)

Cissoko, A., 2023: Au nom de tous les tiens. Montrouge, Éditon du Seuil. (French version; also published in German in 2023 under the title “Kein Kind von nichts und niemand”.)

Dagmar Wolf is D+C’s office manager.

euz.editor@dandc.eu