Water and sanitation

“Every farmer must have an improved latrine”

Why is access to clean water and sanitation crucial for disease prevention?

Water is the basic thing. Without clean water, personal hygiene is impossible, and diseases spread easily. Diarrhoea is the worst problem in the rural areas. But we also struggle with typhus, for example, or trachoma, an eye disease that leads to blindness.

What do you do to address these problems?

In disease prevention, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health focuses on three areas:

- mother and child health,

- hygiene and sanitation and

- control of communicable diseases.

Eight years ago, we started a programme using health extension workers who visit the households and provide clinical services at health centres and health posts in all parts of the district. Since then, child mortality has been decreasing, for example.

What are the main challenges in this area in regard to water and sanitation?

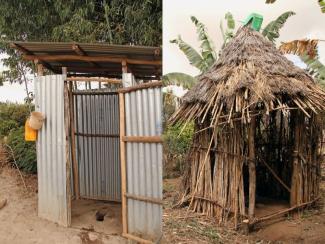

We do not have enough wells. According to the standards of the World Health Organization, every household should have access to a safe-water source within 1.5 kilometres. At the moment, only 68 % of the households in Meskan do so. Furthermore, there should be two health extension workers for every 5000 people, and we haven’t achieved that standard either. The construction of latrines is a huge problem too. Only 57 % of the households have latrines at all, while very few households have improved latrines which are deeper, better protected and have a cover. However, even those who do have latrines, do not necessarily use them.

Why not?

Well, they are not accustomed to it. It is a question of norms and culture. But we are educating the farmers about the advantages of latrines. Our goal is to eradicate open defecation completely. The health extension workers have trained 789 volunteers from the communities, the so-called health development army, and they educate the local people.

Do you see any progress compared with the time before the programme started?

Oh yes, there were a lot of improvements. Four years ago, when the programme against open defecation started in Meskan, only 18 % of the farmers had a latrine. Through our health extension workers, mother and child health improved, and child mortality decreased. The main cause of death for under five year-olds is pneumonia, and about one third of affected children used to die. Now, that number stands at 12 %. For diarrhoea, the second most important cause, the rate improved from 30 % to 20 %. That’s because people have learned to take their children to the health centres or health posts when they are sick. About a third of all deliveries today also take place at health institutions. Eight years ago, that share was only four percent. The immunisation rate improved a lot too. The government’s rota virus immunisation campaign contributes to reducing mortality as well.

What needs to be done so that one day all people in your district will have access to clean water and sanitation?

Well, we have to keep working. We need more wells so that every household can get safe water in an appropriate distance, and every farmer must have an improved latrine.

How much does such a latrine cost, and do you give any support to the people to construct them?

The construction of an improved latrine costs 2500 birr (about 100 euros). We don’t give any financial support, but we have instructed young men from the communities how to make cement covers, and they help the farmers to do it. The programme is called sanitation marketing. For the young men, it is a job opportunity: we give them start-up capital as a grant, so they can start a business making those latrine lids.

Is there any contribution from donors or NGOs in this field?

Yes, there are local NGOs such as GTM (see box) constructing safe water wells with the help of international donors, for instance, and that is very helpful. There is also the One WASH National Programme, which is supported by the World Bank and the African Development Bank. In its context, we are constructing communal latrines in one town, near the market and the bus station. Our main problem remains the budget – like in many African countries.

Ibrahim Awol is vice head of the health office of Meskan.