India

Santal worries

In recent years India has seen an enormous amount of political agitation, rallies and even violent protests. They were directed against corruption, gender-based violence and other grievances. The participation of college and university students, most of whom are urban-educated, was noticeable. They are vocal, independent, energetic, enlightened and have dreams about their future. This is the liberal and progressive face of Indian youth.

These youngsters do not represent their whole generation in India. There is another youth, living far away from the reach of the powerful media. National political agitation hardly concerns them. They have their own pressing issues to deal with. They are the young generation of India’s Adivasi (tribal) communities. Adivasis make up eight percent of India’s population, and 40 % of them are in their 20s or younger.

We Santals are the second largest tribal group in India, counting about 12 million people. Our people mostly live in the sates of Bihar, Orissa, Jharkhand, Bengal and Assam. Until the 18th century, our tribe was one of hunters and gatherers, roaming the Chotonagpur plateau, but today, we are a settled tribe. Agriculture is our prime occupation.

According to the Indian Census of 2001, 95 % of Santals in West Bengal live in rural areas, and 53 % of them are agricultural labourers. The rest are unskilled workers employed on a daily basis, and a tiny number of them work in teaching or office jobs.

After the implementation of Right to Education Act 2009, the enrolment of Santal students in schools has increased, but the dropout rate is very high at almost 50 %. Adivasi youth who drop out of school normally do not enroll in school again at a later point, nor do they settle for a training programme. Most of them realise that, even after getting some education, their family land is the only source of sustenance.

The population is growing fast, however, and small landholdings are becoming ever more fragmented. They cannot provide livelihoods for all members of extended families.

In the lean seasons, many young people therefore migrate to neighbouring districts and states, sometimes along with their family members to work in agriculture or in other contractual jobs. Their work tends to be unregulated and informal, so they do not get the legal minimum wage and are not protected by labour laws and other security measures. Basically, they are at the mercy of landlords. All too often, women and children are physically and sexually exploited.

Frustration and violence

In May 2012, two Santal labourers from Jharkand state were brutally murdered near Illambazar in West Bengal. Young local men, who had come to molest their women, poured acid on the men at night. The local police, administration and political parties did not help the victims because they were from another state. Santals later organised a protest rally in Illambazar with Babulal Marandi, the former chief minister of Jharkhand, but the issue did not get the attention it deserved. There is a long history of Santals’ grievances being largely ignored by mainstream society.

Santal youth who live near the hills or in the coal-producing areas of Jharkhand and West Bengal aspire to work in the collieries or stone-crushing factories which have been started by national and international companies. India’s mineral-rich areas are mostly populated by Adivasi communities (see Aditi Roy Ghatak, D+C/E+Z 212/06, p. 234 ff.).

Resource exploitation often triggers violent conflict. In 2008, for instance, the police shot at Santal youth who were protesting against the government acquiring tribal land in order to let a Kolkata-based company build a power station. The officers killed two and injured dozens.

Corrupt politicians and government officials, vested interest mafiosi and money-lenders dominate matters in resource-driven tensions. Often, divide-and-rule policies serve to keep the people fragmented, helpless and insecure about their future.

The saddest aspect is that many semi-educated dropout youth are lured with money and power to serve criminal masters and exploit their own community. Ultra-left wing radicals, popularly known as Naxalites in India, also take advantage of frustrated Adivasi youth, recruiting them into militias or using them as human shields in their guerrilla war against state agencies.

Succeeding in education

Only a few bright students are lucky enough to graduate from school and even college. Those who do almost always have someone who lends them special support and nurtures their motivation to move ahead. Typically, they will soon move to towns and cities to lead a middle-class life there. Santal villages normally do not benefit much from the educational success of individual youngsters.

Government agencies have been implementing various development programmes for tribal youth with their financial resources and administrative machinery. Other players in the developmental scenario are various Christian and Hindu religious groups, political parties and numerous non-governmental organisations.

There has been some progress, but much remains to be done. Every group has its own philosophy and agenda for working with Santals, and the Santals do not always benefit. Government programmes tend to be cumbersome and inefficient for instance.

Political parties tend to mobilise Santal youth, asking them to march along with drums and colourful dresses in rallies and demonstrations. The idea is to project a pro-poor and pro-grassroots image, though such events typically have no direct link to Santal’s daily lives. It is bizarre, for instance, to see young Santals shouting in Kolkata streets against price hikes of diesel, petrol and cooking gas. These fuels are not used much in the villages.

Religious organisations run schools and hostels for tribals. They are known for their excellent health-care services. Christians have done pioneering work among Santals, especially in education. However, their engagement has always remained under the shadow of the suspicion that their real aim is to convert Santal children to Christianity. The same initiatives have been accused of creating divisions in the community by fostering a new Christian elite within it.

Hindu organisations, in turn, are blamed for the “sanskritisation” of Santal culture. That means that they ignore the special features of tribal culture by making Hindu and tribal culture look very similar. Santal culture, however, has no social hierarchy like the caste system Hindus have, and introducing such notions is destructive.

Mental hurdles

The obstacles to personal and socio-economic development for Santal youth are not always the lack of ideas or resources. Psychological blocks matter too. It can be hard to break away from tradition, and formal education offers little help in such cases.

An example is Mistri Kisku, an educated Santal youth, who once came up with the idea to start a barber’s shop in our village. There is no such shop in our village, and most neighbouring villages don’t have one either. The only two barber’s shops in the area are run by non-Santals, and people have to wait in queue to get a haircut.

All of us were excited about Mistri’s plan. None of us had ever worked in this profession. A professional barber from a nearby town agreed to train him, but in the end, Mistri shied from grasping the opportunity. The reason was that his mother disapproved of his idea. She spoke of a “non-Santal profession”, and the young man timidly accepted his mother’s opinion against his own interest.

As I have written in this magazine earlier (D+C/E+Z 2012/09, p. 333 ff.), it is hard for Santal youth to switch from an egalitarian and agrarian mindset to a competitive commercial one. Because of the non-commercial attitude, there hardly are successful business people among Santals.

Mistri is an example of traditional thinking becoming an obstacle on the road to personal success. Some educated Santals even argue that our culture is opposed to modernity. They miss the point, however, that our cultural heritage is valuable too. In view of mistrust, poverty, exploitation, helplessness and confusion, many Santals find comfort in our community’s values and traditions.

Our cultural heritage is indeed rich. Social researchers and anthropologists admire our way of life, household organisation and traditional social administration. Santals are passionate about our language, dance and music – as well as of our self-made rice beer. Song and dance play a vital role in keeping Santals connected to the community. The songs are beautiful and are rendered with passion. They have basically remained the same even in spite of the aggressive incursion of Bollywood culture in the villages through television, video shows and electronic gadgets.

In search of balance

What Santals really need is a balance of tradition and modernity. Some educated youth like Rathin Kisku from West Bengal and Lalsushant Soren or Stephen Tudu from Jharkhand are now engaged in fusing traditional Santal music with mainstream Indian music. Most Santal youth appreciate their work, whereas traditionalists like Ram Kisku, an eminent Santal singer, warn that the essence of our music will be lost.

Sibu Soren is a high-school teacher who found his personal balance. He is from a Santal village, but moved to the small town of Santiniketan, hoping to live a comfortable life there. He sent his children to a private school and bought two motorcycles – one for himself and one for his wife. His parents in the village were proud of his achievements and projected him as a role model, saying that “this is how an educated Santals should live”.

After a few years, however, Sibu realised he missed his cultural ambience. Life among the Bengali people of Santiniketan seemed suffocating and empty, so he returned to his village. Presently, he is running an evening school there with other educated friends. He also publishes a magazine in Santali and has formed a Santali drama and music group. The Government of West Bengal recently felicitated him for his contribution to Santali culture. He has indeed become a role model. Sadly, only very few Santal villages have someone like him.

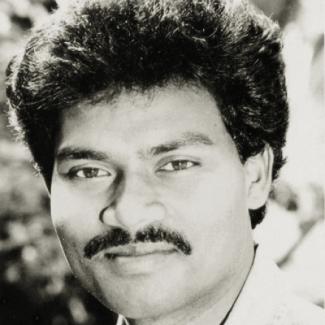

Boro Baski is a teacher and social worker with the community-based organisation Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha in West Bengal. He was the first person from his village to go to college as well as the first to earn a PhD (in social work). The Adibasi Seva is supported by the German NGO Freundeskreis Ghosaldanga und Bishnubati.

borobaski@gmail.com