Taxation

Prudent taxation requires national action plus global cooperation

National governments made a commitment “to enhancing revenue administration through modernised, progressive tax systems, improved tax policy and more efficient tax collection,” in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda. It was adopted by the UN summit on Financing for Development in the Ethiopian capital in 2015. The document proved that the relevance of public finance in development is widely acknowledged.

In order to improve living conditions, developing countries must increase the state revenues that enable them to invest in infrastructure and social services. Policies that drive economic growth are not enough. Governments must expand the tax base too. Good tax policies are beneficial in several ways:

- They contribute to making development more inclusive, because they tackle (both income and gender) inequalities by placing heavier burdens on the haves.

- They discourage environmentally and otherwise harmful behaviour.

- They strengthen the social contract by involving citizens in efforts for the common good, thus attracting taxpayers’ attention to the quality of governance and democracy.

All of this matters for SDG achievement. It also contributes to building more capable statehood. National sovereignty is enhanced when sufficient domestic revenues reduce governments’ dependency on official development assistance (ODA). If they implement inclusive and sustainable policies on this basis, they reinforce democracy.

While developing countries obtain a significant share of their development finance from domestic sources today, their tax collection ratio rests at about half of that of developed countries. Accordingly, improving domestic resource mobilisation (DRM) is a core issue of international development debate.

More tax revenues are possible

In 2020, low-income countries’ tax-to-GDP ratio was 11.6 % in contrast to 16.3 % in other developing countries and 23.2 % in developed countries, according to the UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development). The ratios had been slowly improving since the 1990s, but multiple crises have made things more difficult once more. In particular, the Covid-19 pandemic and the worsening climate crisis have made government debts grow fast.

According to a 2023 IMF study, emerging markets and developing countries could mobilise more tax money. The document suggests that low-income countries can increase their intake by 6.7 % on average, while the comparative figure for emerging markets is five percent. To tap this potential, governments are told to adopt appropriate policies. Doing so, however, will require political will, especially in regard to improving tax enforcement.

People obviously do not like to pay taxes. Increasing rates and broadening the base is therefore politically quite challenging. Loopholes must be closed. So far the wealthy are yet to contribute their fair share to society, while important taxes, such as wealth and property taxes, are underutilised. Moreover, it is necessary to fight corruption and ensure good administration of tax laws.

A nation’s social contract must remain fragile if masses of people stay outside the public-finance system. Not taxing a large share of the people means that governments lack the funding they need to improve the plight of low-income households. Marginally taxing the incomes of the larger public to the benefit of targeted state action in fields like education or healthcare is essential for SDG achievement. The benefits of such state action far outweigh what private spending by taxed families would deliver.

Illicit financial flows

The nation-state level, however, is not all that matters. Tax-related illicit financial flows (IFFs) diminish government budgets in developing countries.

Indeed, tax evasion, tax avoidance and tax planning cause serious harm. Multinational corporations benefit in particular. The exact amounts of IFFs are hard to pin down, but no one doubts developing countries are losing significant sums.

IFFs cost developing countries around $ 800 billion in the decade from 2004 to 2013, according to a World Bank estimate of 2021. Of the total, about $ 500 billion would have been collected as taxes, of which up to 70 % would have been corporate taxes. Africa’s yearly revenue loss is estimated at over $ 50 billion. A troublesome trend is that the digitalisation of economies further facilitates harmful tax practices and tax evasion.

It is widely appreciated that international cooperation on tax policies and their enforcement is needed. The agenda has so far mostly been driven by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – an umbrella organisation of high-income countries. The UN, World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) are also among the institutions that support related policies.

While OECD efforts have made progress in recent years, they remain controversial too. Fairness, inclusiveness and efficiency are in dispute. Governments of developing countries demand to be involved in international rule making at eye level moreover. They want the UN, in which they have equal say, to handle matters.

Indeed, the UN is becoming more assertive. Late last year, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 78/230 with an eye to crafting an UN-led framework convention for international tax cooperation.

According to a Nigerian diplomat, the goal is to enable “developing countries to mobilise domestic resources, directly fuelling development projects and social welfare programmes.” An ad-hoc committee was set up to prepare the terms of reference for the framework convention. It is expected to conclude its work by August this year, building on work done previously by UN secretary-general António Guterres and the FACTI Panel (High-Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity for Achieving the 2030 Agenda).

Deep divide between developing and developed countries

The resolution was controversial, however. The 125 governments that voted in favour mostly represented the developing world, whereas the 57 opposing and abstaining votes mostly came from the global north.

That developed countries voted against the resolution was no surprise. EU institutions and member countries, for example, had argued that the transfer of power to the UN would undermine progress made by the OECD processes. Civil-society observers, on the other hand, point out that privileged OECD members generally prefer settings in which they call the shots. It is also worth noting that business associations in high-income countries have endorsed OECD initiatives.

High-income nations generally promise to support capacity building in tax administrations and to apply global tax standards, but they normally prefer non-binding options to the binding UN tax convention. Non-governmental tax-justice advocates regard this approach as contradictory at best.

Powerful governments keep praising what they call “the rules-bound world order”. Developing countries would find the global tax framework more convincing if the processes permit an equal say in rule making, leading to the development of rules which serve their interest. Capacity building in tax administrations and cooperation on international tax standards is simply not enough. Policymakers in developing countries consider IFFs to be the most pressing issue, so they demand an equal say in the proposed solution.

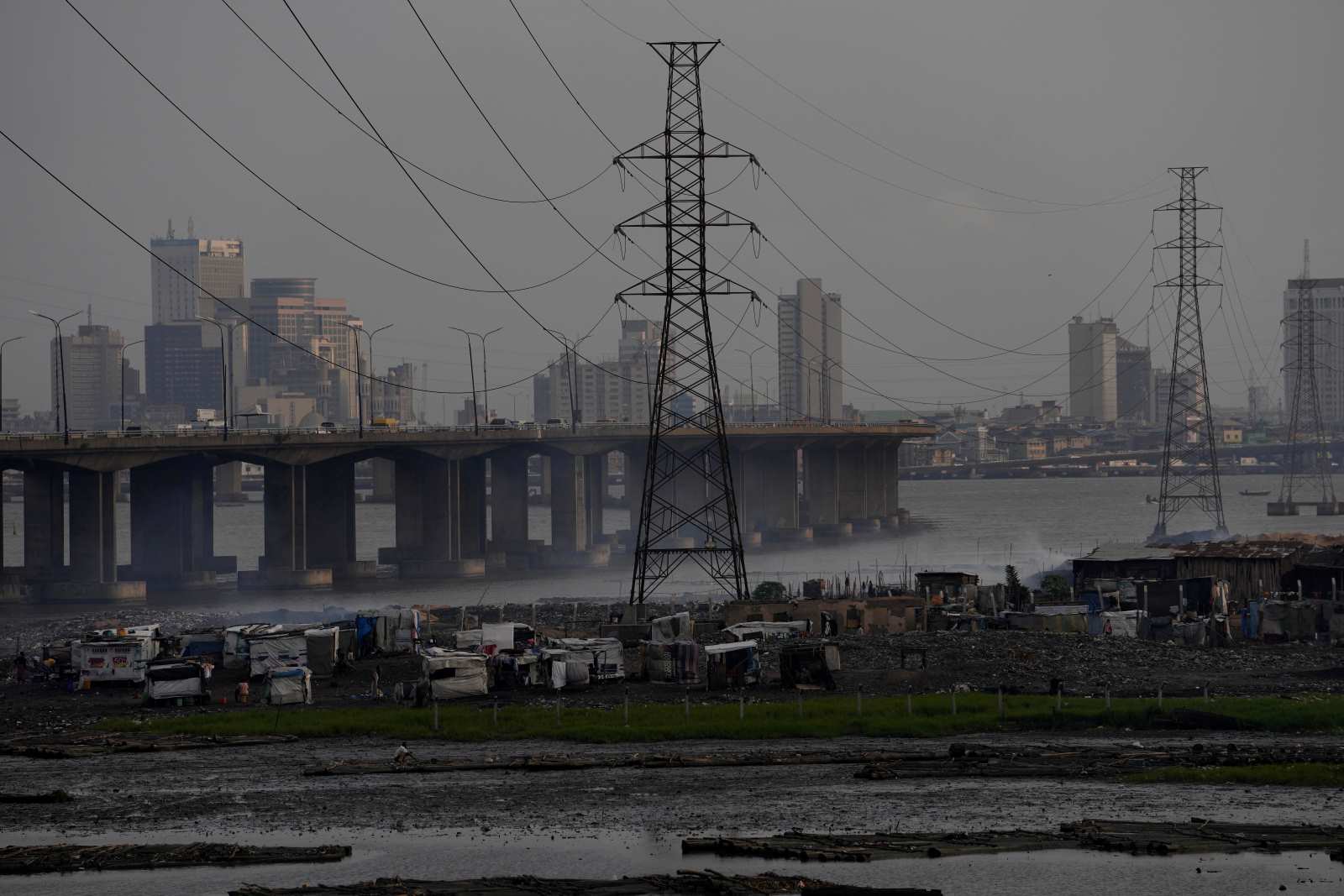

Taxation is an inherently political matter. It reflects a sovereign nation’s values and preferences. Nonetheless, international coordination is needed, as economies are interlinked. Capital flows across borders easily and digitalisation is easing such flows further. Some jurisdictions intentionally create fertile grounds for multinationals’ profit shifting and secrecy. They thus erode the revenue base of developing countries. Unsurprisingly, prosperous capital-exporting nations figure prominently in the former group, while the capital importing global south dominates the latter. For the sake of balance, the UN, in which all parties are represented, would be the right forum to tackle unfair tax-haven policies.

Lessen ODA dependency

So far, ODA flows to disadvantaged countries remain essential for SDG achievement. The stronger those countries’ tax systems become, however, the less ODA dependent they will be. Building public-finance capacities should therefore be a priority of development cooperation. Related measures do not only strengthen state capacities, but can also improve democratic governance when policy results improve, and more people become involved in public affairs. By contrast, weak fiscal systems typically go along with deficient social contracts, unsatisfying economic performance and huge social disparities. Consequences include conflict, fragile statehood and forced migration.

It is essential to facilitate strong public finance systems in developing countries. That certainly requires action at the national level. However, appropriate international cooperation is needed too. High-income nations should therefore support a UN framework convention on taxes and not insist on monopolising decision-making in the OECD context. Donor governments should heed independent experts’ advice in this matter.

Altayesh Taddese Terefe is an economist who works for the International Tax Compact (ITC), which is implemented by GIZ. This essay expresses her personal views and not official ITC or GIZ policy.

altitad@gmail.com