Displaced by conflict

“I wanted to die in Nagorno-Karabakh”

Irina Baghdasaryan has lost everything. It’s now two years since she was forced to flee from her home region of Nagorno-Karabakh. The 38-year-old Armenian remembers the day – 19 September 2023 – with horror. She lived with her family in the village of Chankatagh in the Martakert region. That Tuesday morning, she heard that Azerbaijani troops had invaded. Everything happened so quickly that she didn’t even have time to take a family photo down from the wall. By the time the family fled with their four small children and 81-year-old Grandmother Raya, their village was already surrounded by the Azerbaijani military.

Somehow, they managed to find a way through and escaped into the forest. They ran all night, pursued some of the time by soldiers. They had nothing to eat with them, nor any water, and only the clothes they were wearing. While on the run they saw an Armenian tank blown up by a grenade before their very eyes. Eventually they came across some Armenian soldiers who took them by truck to Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh. There they spent four days staying with acquaintances before traversing the Lachin corridor – the only land route into Armenia from Nagorno-Karabakh, which is in Azerbaijani territory – in a bus jam-packed with refugees.

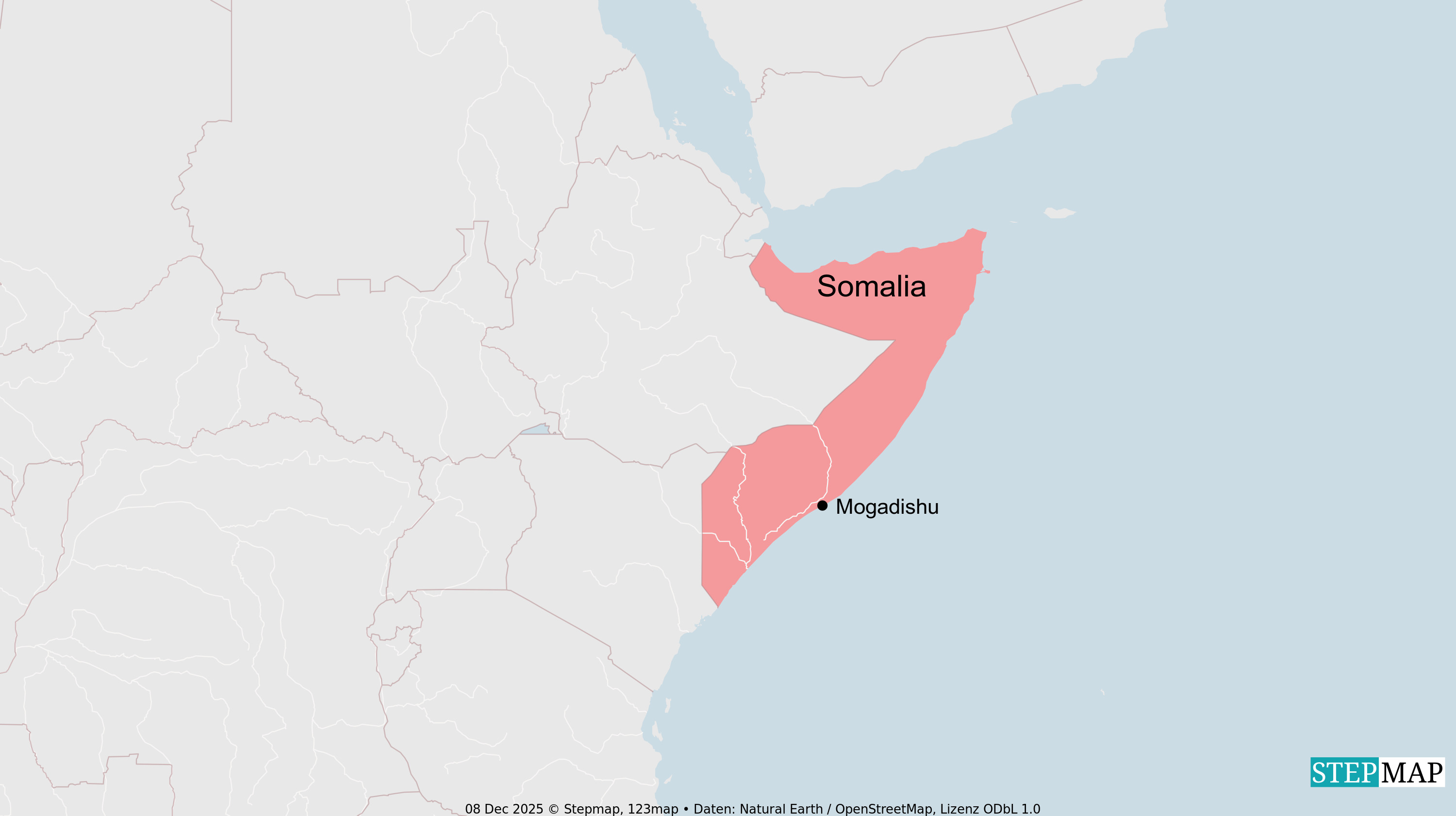

The Baghdasaryans share their fate with around a hundred thousand of their compatriots. The seizure of Nagorno-Karabakh brought thousands of years of Armenian settlement in the region to an end. Azerbaijan, a predominantly Muslim country, occupied the Christian Armenian exclave and drove out all the Armenians living there. This ended the armed conflicts that had kept flaring up between the neighbouring states for decades. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the two former Soviet republics had repeatedly waged war against one another. Armenia was victorious initially and conquered a large chunk of territory around Nagorno-Karabakh; later, Azerbaijan recaptured the area and, by driving out the Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh, established an entirely new set of circumstances.

These days, Nagorno-Karabakh is largely deserted. Allegedly, a number of Azerbaijani soldiers have been relocated there with their families. In August 2025, the governments in Yerevan and Baku signed an agreement pledging to recognise each other’s territorial integrity within their existing borders.

Support from civil society

The Baghdasaryan family was initially met in Armenia by the civil-society organisation Syunik-Development in Yeghegnadzor, the capital of Vayots Dzor province in the south of the country. Syunik-Development says its mission is to promote Armenia’s regional populations in solving their current social, economic, environmental and educational issues.

The organisation was a 1995 initiative of the diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church in the region, specifically of Archbishop Abraham Mkrtchyan, Syunik-Development’s founder and current board chairman. This was the period following the collapse of the Soviet Union when the newly independent Armenian state had yet to redefine itself and a lot was happening in the capital Yerevan but very little in rural areas.

The urban-rural divide remains one of Armenia’s biggest structural problems to this day. Everything is concentrated on Yerevan, where economic growth has become detached from that in the rest of the country and prices are on a par with those in Western European cities. Meanwhile, provincial areas are suffering from underemployment and low incomes.

From emergency aid to educational programmes

“One of our most important challenges in 2023 was to provide refugees with emergency aid,” says Project Coordinator Hayarpi Aghakhanyan. “It was a question of meeting their basic needs for things like food, clothing and medical care. The second step is to make lasting support available in the form of housing, educational programmes, youth work and social work.”

The Baghdasaryan family also benefited from this assistance. After an initial period at a refugee centre, they found a flat in Yeghegnadzor with Syunik-Development’s help. The family is still eking out an impoverished existence there today. Irina Baghdasaryan, formerly a management assistant at a gold mine in Nagorno-Karabakh, has failed to fully integrate into society in Armenia’s heartland – despite all the help provided following the family’s flight and despite the considerable solidarity shown by her new neighbours. She is divorced and unemployed. Her ten-year-old son Artur has been traumatised ever since they fled from Nagorno-Karabakh and needs a great deal of care and attention from his mother, making it impossible for her to go out to work.

The family is reliant on the meagre pension paid to Grandmother Raya – now 83, she had worked as a cleaner in Nagorno-Karabakh. Dressed in black, the emaciated old lady hides her face in her hands, with tears coursing down her cheeks, as she talks about the family’s escape. “I wanted to die in Nagorno-Karabakh and be buried there,” she says. “But then we lost everything, even our own grave.”

The Ishkhanyan family, who these days live in a small house on the outskirts of Yeghegnadzor, suffered a similarly harsh fate. They were even forced to flee twice: from their home town of Shushi during the war in 2020 and then again in 2023 from Stepanakert, where they had moved when the hostilities ended in 2020. Unlike the Baghdasaryans, however, they have built a life for themselves in Armenia. Armen Ishkhanyan works as a long-distance lorry driver and his wife Gohar as a designer. Although they have integrated, they will never give up hope of one day returning to Nagorno-Karabakh, says Gohar Ishkhanyan. They have chosen not to take Armenian citizenship, fearing it could pose an obstacle to their return.

Dependent on Russian gas

A modern solar thermal system is installed on the roof of the family’s house. It was funded by Syunik-Development, explains Project Coordinator Aghakhanyan. “This enables the Ishkhanyan family to save on heating costs during the winter.” Armenia is dependent on Russian gas and buys it at relatively low prices. Nonetheless, rural households in Armenia have little in the way of purchasing power, so gas bills in the long, cold and snowy winters of the southern Caucasus hit them hard. The solar thermal system is thus of huge benefit to the Ishkhanyan family.

“We are funded by the Church and by donations from international partners,” says Hayarpi Aghakhanyan from Syunik-Development. She names German charity Brot für die Welt and the European Commission as examples of foreign donors. Their international partners are based in 20 different countries, for the most part in Western Europe. However, they also include Georgia and Russia – two states with which Armenia enjoys a special relationship. A not inconsiderable proportion of the organisation’s funding stems from donations from Armenia’s global diaspora. An estimated 8 to 10 million Armenians live abroad, whereas the population in Armenia itself numbers only around 3 million. Many Armenian expats have built successful lives for themselves in Europe, the USA or Russia. The ties between the diaspora and their compatriots at home are traditionally close.

Following the surge of refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh in the autumn of 2023 and the need to provide them with emergency aid, Syunik-Development has gone back to focusing on the region’s medium- and long-term development. In Yeghegnadzor, its activities revolve around agricultural initiatives, nursery schools, educational programmes, promoting neighbourhood help schemes and around youth and social work. As the organisation’s website explains, the goal is to help establish a stable and democratic society in Armenia that is better prepared to meet the social, cultural, economic and environmental challenges of the 21st century.

André Uzulis is the editor-in-chief of loyal, a German monthly with a focus on security policy.

andre.uzulis@fazit.de