Power struggle

Dialogue may yet ease tensions in Côte d’Ivoire

On 6 August, Ouattara surprisingly declared he would run once again on 31 October. Previously he had promised to retire, but then Amadou Gon Coulibaly, his prime minister, suddenly died in July. Coulibaly was supposed to be the presidential candidate for Ouattara’s party, and the president said it was his “citizen’s duty” to run again.

He is 78 years old and has served for two terms, first elected in 2010 and re-elected in 2015. The constitution limits terms to two for the head of state, so the opposition considered him an unconstitutional candidate this year. The counterargument was that the constitution was amended in 2016, so the count was re-set and Ouattara’s previous terms do not matter anymore.

The Constitutional Council has the final say on electoral law and allowed Ouattara to run. It did, however, bar Laurent Gbagbo and Guillome Soro, a former president and a former prime minister respectively. The International Criminal Court (ICC) tried Gbagbo for post-election violence in 2010, but acquitted him last year. Soro was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment by a court in Abidjan for embezzlement and money laundering. However, the African Court on Human and People’s Rights argued that both men’s civic rights in Côte d’Ivoire must be restored, but the Ivorian authorities so far have ignored that judgment. Both are living in exile in Europe.

In 2010, Gbagbo denied Ouattara’s evident electoral success, clinging to power with support from the security forces. About 3,000 people died in clashes. Only after the French military intervened, could Ouattara, a former official of the International Monetary Fund, take office. Western governments consider him a reform-oriented policymaker, but critics point out that they should have spelled out clearly that a 3rd presidential term would be unacceptable.

Led by Bédié, who was the country’s president from 1993 to 1999 and is now 86 years old, the opposition began calling for civil disobedience in summer. It stated that Ouattara was not a legitimate candidate this time and demanded that both the independent election commission and the Constitutional Council be reformed. The government’s influence on both was said to be too strong.

85 dead

Many opposition supporters did as they were told. However, there was violence. According to the government, 85 people were killed and 484 wounded. To some extent, the violence reflected ethnic divides that had spawned the civil strife in the early years this millennium. As in many Sahel countries, there are serious frictions between the comparatively poor and predominantly Muslim north and the more prosperous and mostly Christian south. Immigration from poor neighbouring countries has exacerbated tensions.

Participants in the recent boycott campaign say they did not initiate violence. They claim that others provoked it. Amnesty International, the human-rights organisation, has reported that the police got support from violent young men when dispersing rallies.

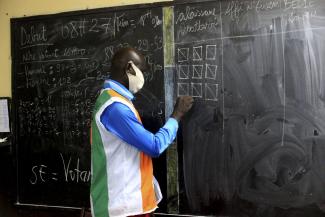

On 31 October, only 53 % of citizens went to the polls, but 94 % of them voted for Ouattara. International observers from the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) and the Carter Center have declared that the political and security context were not conducive to a fair and credible presidential election. Two days later, the opposition announced the establishment of a national transitional council led by Bédié. The idea was that it would create the conditions for a transparent and inclusive rerun of the election. The government responded by arresting opposition leaders, speaking of an attack on the authority of the state. Thousands fled the country.

Opponents on talking terms

The tensions seem to be dissipating however. Ouattara and Bédié met in a hotel in Abidjan on 11 November. It inspired hope that they were on talking terms. However, Bédié soon declared he wanted all arrested persons to be set free and refugees to be able to return home safely. Making matters more complicated, Gbagbo supporters wanted that to apply to their exiled former leaders.

People hoped the Ouattara-Bédié dialogue would reduce the tensions. The situation was difficult – but not as desperate as it was during the rebellion of 2002 or the post-election crisis of 2010.

In mid-December, Ouattara was sworn in for a third term. His new cabinet includes an opposition leader as minister for reconciliation. Other opposition leaders still dispute the legitimacy of the president nonetheless.

It is hard to say whether it helps that Ouattara and Bédié are old acquaintances. Indeed, they have been competing for power in Côte d’Ivoire for decades after the death of independence leader Félix Houphouët-Boigny in 1993. Both men started their political careers as his supporters and both later claimed to be his legitimate heir. However, they also formed a coalition of parties they called RHDP (Rassemblement des Houphouëtistes pour la démocratie et la paix) in 2005 and turned it into one party in 2018. The RHDP’s presidential candidate in 2020 was once more Ouattara.

Anderson Diédri is a journalist based in Abidjan.

diedrimanfeianderson@yahoo.fr

UPDATE: The paragraphs in the final section under the sub-headlne "Opponents on talking terms" were updated on 22. December 2020.