Health

Helping AIDS orphans

According to estimates by UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS), more than 15 million children became orphans as a consequence of AIDS in sub-Sahara Africa; that is approximately 90 % of all AIDS orphans globally. On top of that number there are those who lost one or both parents due to conflicts or extreme poverty. In total, there are 55 million orphaned children and youths in southern Africa.

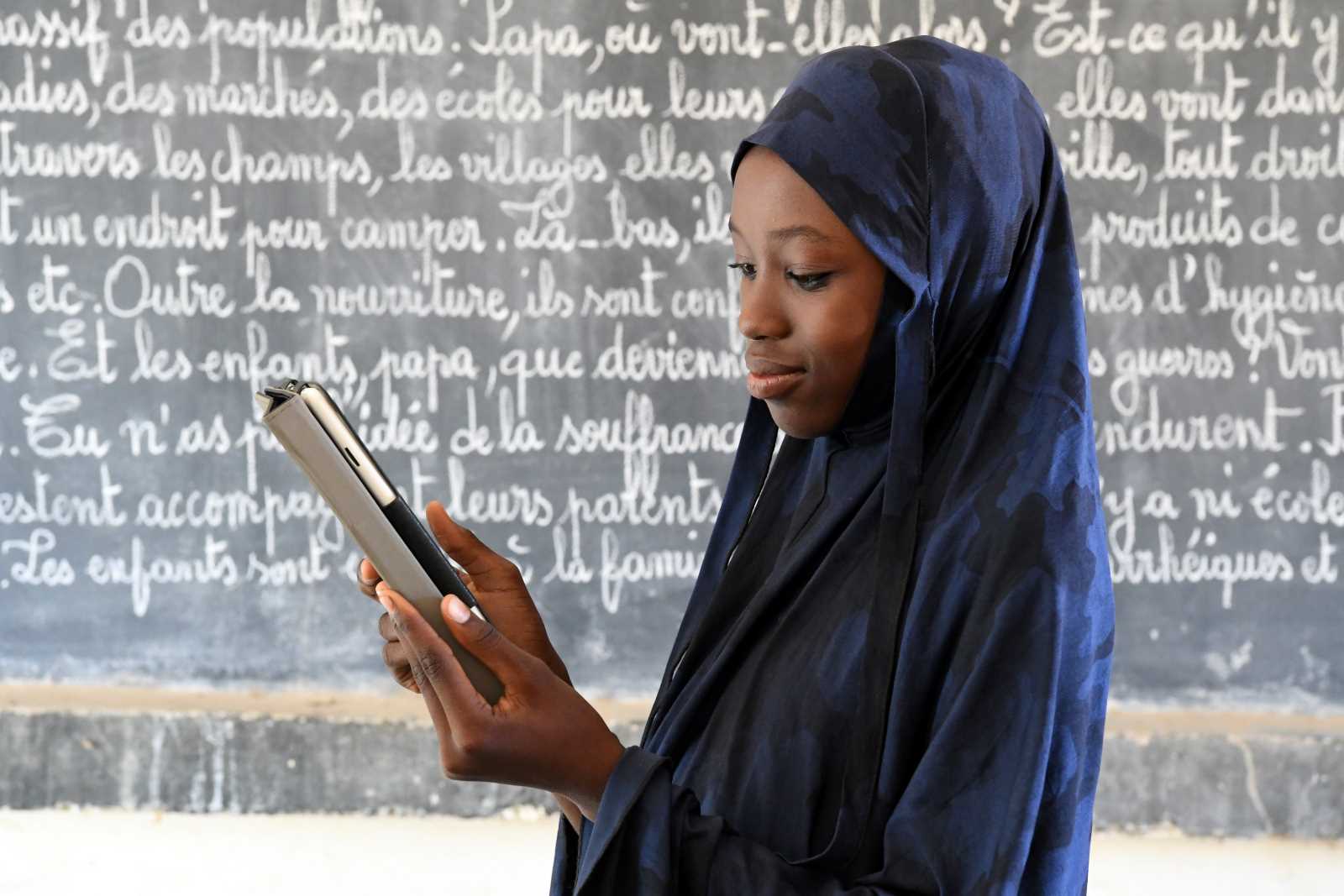

HIV/AIDS has many consequences: Education chances for girls diminish when they are forced to become caregivers at home. As adults die of AIDS, moreover, there are not enough teachers in the schools. Private-sector companies have to train extra personnel for key positions. They know part of their staff will fall ill and even die before their time. Without parents or income, many AIDS orphans live in great poverty. Accordingly, they are more likely to turn to crime. Girls from AIDS-affected families are at greater risk than average to end up in prostitution.

The Regional Psychosocial Support Initiative (REPSSI) provides aid to orphans. The organisation works in 13 countries of eastern and southern Africa and tries to diminish the dire social and emotional effects HIV/AIDS and poverty have on children and youths. Sociologist Kurt Mandörin, co-founder of REPSSI in 2002, stated: “If the children concerned don’t overcome their traumas, entire societies may become dysfunctional.”

Training of paraprofessionals

In a new book about REPSSI, author Richard Gerster describes how this organisation works: it does not employ professional psychiatrists or social workers – doing so would be too expensive. Instead, REPSSI relies on the training of paraprofessional volunteers who are, for instance, grandmothers who grant help in their neighbourhood, not only to their own extended family.

REPSSI relies on grown cultural structures and existing networks. The organisation does not work directly with affected children, but backs various partners in civil society, universities, governments and regional organisations.

REPSSI trains community caregivers at the local level and master trainers at the regional level, so partner organisations have high-quality teachers in matters relating to psychosocial support. This way, regional pools of highly qualified trainers are being created. According to Gerster, the organisation considers itself a centre of competence for psychosocial interventions. It advises governments as well as private organisations.

In order to mobilise resources for AIDS orphans at local, regional and national levels, lobbying is crucial. As Gerster elaborates, REPSSI cooperates with the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the East African Community (EAC) for this purpose. REPSSI has developed an advocacy toolkit for community initiatives that have to deal with government agencies and private-sector companies. Among other things, it shows how to mobilise the local media and make use of awareness raising dramas on stage.

REPSSI is funded by the Swiss government (Directorate for Development and Cooperation – DEZA), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) and the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development (NFSD). According to the author of the book, more than 5 million children and youngsters in southern Africa have benefited from REPSSI’s work so far.