Urgent issue

Fundamental principle

In German eyes, such claims are patently absurd. The pillars of Germany’s welfare state are compulsory state-run insurances that guarantee the coverage of health-care costs and old-age pensions. Otto von Bismarck introduced them at the end of the 19th century and outlawed the Social Democrats at the same time. He was obviously not a socialist. His goal was to keep the labour movement from gaining strength because of unresolved social issues.

It will always be contested what exactly is socially just, what state and society must deliver, and what an individual person’s own obligations should be. The reason is that the haves do not want to be forced to share much, while the have-nots demand more assistance. But in spite of this fundamental dispute, all rich nations have legislation to protect their citizens from risks such as poverty in old age, unemployment and – in most cases – illness. Social-protection systems typically rely on a mix of governmental measures and private efforts. Some benefits are funded with taxes. Others, for instance Bismarck’s insurance schemes, are based on compulsory contributions of beneficiaries. Yet other programmes rely on personal savings. Some governments subsidise private life insurances. The exact design of a comprehensive social-protection system depends on the specifics of the individual country. The same is true of the reforms needed to adapt that system to society’s changing needs.

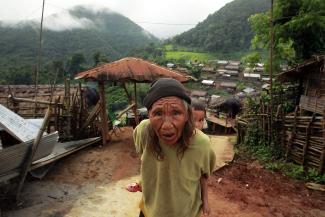

In recent times, the social-policy ambitions of developing countries and emerging markets have grown. Brazil created cash transfers for poor families under the condition that they send their children to school and have them vaccinated. The approach was then turned into a full-blown “Zero Hunger” policy. India invented an employment guarantee to improve the livelihoods of rural families. Innovations of this kind reduced poverty in many places, but they neither serve everyone in need, nor do they cover all relevant risks.

In many countries, ageing has set in. Demographic change means that there are fewer children and more old people than in the past. The nuclear family is beginning to dominate – at least in urban areas. Extended families used to grant members some protection, but that cannot be taken for granted anymore. Unless pension systems become much stronger, the world will see unprecedented old-age poverty.

Sceptics say poor societies cannot afford social protection. They are wrong. Solidarity is a fundamental principle of human life, not a luxury that becomes affordable only at a certain income level. When Bismarck laid the foundations of the German welfare state, his country was only at the beginning of its industrial development. And the American example does not prove that social protection is unaffordable either. The USA spends a larger share of GDP on health care than most rich nations, while its share of people without health insurance is way above average. This setting is neither smart nor fair.

Correction disclaimer: The original version of this editorial, which was also published in our print edition, mistakenly stated that Bismarck introduced unemployment benefits in Germany. The truth is that legislation concerning these benefits was only passed in 1927.