Demographics

Family planning is a woman’s right

At the end of 2022, the world population exceeded 8 billion for the first time, according to the UN. In 2010, there had been 7 billion of us. Another billion was added in only 12 years. In the past 100 years or so, the number rose by 6 billion.

The reasons for population growth include improvements in health care, better nutrition, and advances in medical science. Nowadays, people live longer.

Population growth is slowing down though. It is anticipated that the next billion milestone will be passed in 15, not 12 years. Experts estimate that the world population will peak at approximately 10.4 billion individuals by the end of this century.

Since the 1960s, the growth rate has consistently declined. In the early 1960s, the world population was increasing by an annual 2.1 %. The current rate is slightly below one percent. The global fertility rate has accordingly decreased from 5.3 births per woman 60 years ago to 2.3 births now.

Healthier and longer lives

The global experience is that, as people live healthier and longer, fertility rates decline, and populations become older on average. Data from the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) show that the global share of persons aged 65 or older has grown from approximately five percent in 1950 to around six percent in 1990. Last year, it reached 10 % and is expected to rise to 16 % by 2050.

The global figures, however, do not reveal the full picture. Indeed, the numbers vary widely around the world.

In high-income countries, there is consistent decline in fertility rates, according to World Bank data, with women currently having only 1.5 children on average. Middle-income countries have also witnessed a downward trend, with fertility rates now at 2.2 births. That is slightly above the 2.1 births, which mean that population numbers are basically stable.

In stark contrast, low-income countries continue to exhibit significantly higher fertility rates. Some are twice the replacement level, which is the average number of children per woman required to maintain a stable population size. The fertility rate for low-income countries is currently 4.7 births per woman.

The countries with the lowest per-capita incomes also tend to have the highest fertility rates. A look at the World Bank’s fertility data shows that 32 of the 36 countries with a fertility rate of four births or more per woman are in Africa. The other four countries are Afghanistan, Samoa and the Marshall and Solomon Islands.

The next generation provides a safety net

A crucial issue is that people in poor countries typically lack proper social-security systems. If they want to be taken care of in old age, they need children. The next generation is seen as future providers. It serves as a safety net. At the same time, high infant mortality and poverty mean not all are likely to survive to adulthood.

It also matters that many women marry at a young age. They normally lack opportunities of education and employment. Teenage brides, in other words, are not empowered to determine their fate. Due to traditional gender norms, they are not even in a strong position to negotiate with their husbands and his relatives, who collectively tend to dominate their lives. It is therefore good news that fertility rates in Africa have begun to drop. In many parts of the continent, populations are not growing as fast as they did even 10 years ago.

The plain truth is that if women have choices thanks to better education (very much including sex education), advanced infrastructure and greater prosperity, they tend to have fewer children. That is what the global statistics show. They also show that the desire to live without any children at all is not predominant even in prosperous and secularised societies.

On the other hand, countries experiencing low levels of fertility face a distinct set of safety-net challenges. The share of dependent old-age people is growing, while the working age population is shrinking. The implication is significant costs associated with social security, health care and long-term care. To address these challenges, countries with low fertility rates need to devise sustainable policies. So far, policies to encourage women to have more babies have largely failed. Options therefore include encouraging migration or raising the retirement age.

A double-edged sword

Migration, of course, is a double-edged sword, especially when skilled people who are needed at home, move abroad. On the other hand, remittances benefit their extended families and can drive development. When migrants return home, moreover, they bring along newly acquired skills and knowledge.

It is striking, moreover, that advanced nations do not treat immigrants well. The European Central Bank has reported that approximately 15 % of households in the eurozone are headed by migrants, with two-thirds originating from outside the EU. However, these migrants earn approximately 25 to 30 % less than their non-migrant counterparts. At the same time, they contribute more to taxes and social-protection systems than they receive in benefits. Nonetheless, populist politicians keep claiming that migrants only want to exploit welfare systems.

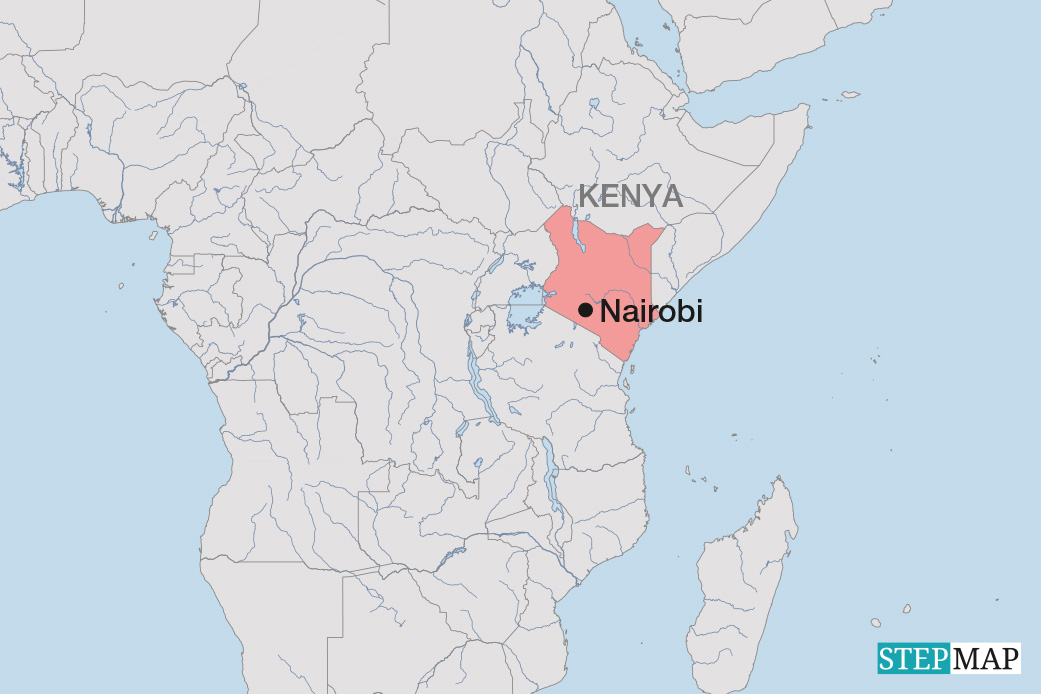

Mahwish Gul is a Nairobi-based consultant who specialises in development management.

mahwish.gul@gmail.com