Review essay

Nuanced assessment

Media reports about agriculture often focus on mechanised, large-scale farms. However, such farms are in the minority worldwide. Around the globe, there are 450 million farms with less than two hectares of land. They are operated by households made up of more than two billion people. These smallholder livelihoods vary considerably. They range from successful, highly productive and innovative economic units to poor subsistence farms run by people who do not enjoy food security.

It is no new insight that "smallholder farmers" differ from one another, even within a single region. Scholars have been focusing attention on the differences for about a decade, relying on improved methodology and data collected at household level. Empirical studies show that in many countries, farming households earn their income from an ever wider variety of sources thanks to dynamics in agricultural markets as well as in the rural non-farm economy.

In 2006, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published an important study, distinguishing five categories of farms and rural households, ranging from commercial large-scale businesses to small-scale subsistence operations. Every category needs different kinds of policies. For the poorest, public welfare schemes are required. This publication was ground breaking because it spelled out once and for all that smallholders are not all the same.

Based on the OECD paper, Dorward et al. (2009) use three catchy terms to categorise the development potential of smallholder farms: “stepping up”, “hanging in” or “stepping out”. Whoever wants to support them must design intelligent and differentiated policies. Relevant aspects include:

- improving farmers’ access to markets,

- the generation of jobs in the non-farm economy and

- social transfers to improve the standard of living for the poorest.

Policymakers are advised to promote rural transformation, taking into consideration social and demographic differentiation. Unless they do so, rural-development policies cannot succeed.

Who can be integrated and how?

Hazell and Rahman (2014) offer a very good overview of the current state of development research on smallholder farmers. The authors cover most of the important topics in 17 chapters. They show that it is possible to effectively involve smallholder households in commercial agriculture. They also elaborate why this must happen.

Millions of smallholder farmers have made enormous advances towards commercialisation. Many of them have proven that they can operate more intensively, sustainably and productively than large farms. Provided they generate enough income, moreover, smallholder farms can absorb excess workers in countries suffering high levels of unemployment. This book is inspiring due to the authors' descriptions of the opportunities provided by technological innovations, dynamic agricultural markets and improved market access.

Wiggins and Keats (2013) present a worthy survey of successful African policies and projects. They discuss more than 30 case studies of agricultural projects and value chains in over 15 countries. They emphasise the importance not only of market-stimulating instruments, but also on appropriate approaches to the rural investment climate.

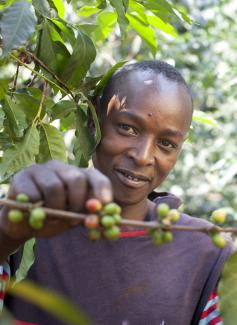

The cultivation of high-value export goods such as coffee, tea, cacao or cotton has provided many smallholder households with good and reliable sources of income. When it comes to staple crops, however, commercial agriculture has not yet proven similarly successful, as the authors point out. Based on this insight, they argue the case for input subsidies and related government interventions. Such measures, according to them, would boost self-reliance in countries where food insecurity endures.

Wiggins et al. (2013) summarise the agricultural development agenda in 12 topics in a background paper which was prepared at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) on behalf of Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the GIZ. The paper points out that there is consensus on many issues. For instance, it is uncontroversial that the provision of rural public goods (such as road infrastructure) can have a great impact. This ODI paper stresses that policymakers should consider such consensus.

Other policy approaches, however, are controversial. Government interventions in agricultural markets – fertiliser subsidies, for example, – should therefore be based on a careful analyses of underlying market and policy failures and a thorough assessment of the political economy of the agricultural sector.

Vorley (2013) takes a more critical view of the commercialisation of smallholder agriculture. The scholar from the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) examines, among other things, the opportunities that informal markets offer to small farmers. He argues that very few small farmers are capable of becoming part of formalised, export-driven value chains.

In development discourse, informality is often seen as an obstacle to the development of a modern private sector. Vorley, however, highlights the advantages of informal trade for smallholders (such as low barriers to entry, flexibility, resilience). Rising food prices, moreover, should benefit famers in informal markets. In Vorley’s view, policy interventions and development projects should therefore focus not only on including small farms into value chains, but also promote informal production and local marketing.

Vorley’s report confirms what the other publications mentioned above state in regard to the increasing differentiation among smallholders. In this respect, it takes effective welfare policies and not merely market-based instruments to help the poorest of the rural poor.

Practical experience

German development agencies have a long history of promoting inclusive business models that involve private-sector companies and smallholder farmers. The GIZ and other agencies help to train farmers and establish producer groups that can engage collectively in marketing as well as procurement. Agencies equally provide advice on making agricultural value chains more inclusive.

The GIZ often plays the role of an "honest broker" and supports the development of fair and sustainable business relations among all participants. On behalf of BMZ, it produced a publication towards the needs of the private sector in 2012. The booklet proposes options for cooperating successfully and inclusively with smallholders along the entire value chain.

Another GIZ publication (2013) offers practical instructions for how smallholders and buyers can cooperate in innovative ways. This handbook does not provide blueprints. Instead, users can develop context-specific solutions ranging from contractual agreements to rather informal arrangements.

Smallholder farms will continue to dominate global agricultural production for the next 50 years. Accordingly, the promotion of differentiated measures that meet their divergent needs will remain a top priority on the international development agenda.

Ingo Melchers heads the sector programme Agricultural Policy and Food Security for the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ).

ingo.melchers@giz.de

Heike Hoeffler works for the same GIZ team.

heike.hoeffler@giz.de

Ellen Funch works for the same GIZ team.

ellen.funch@giz.de