Eco-friendly farms

Organic potential in Europe’s poorest country

With a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of only $ 2,136 per capita in 2012, the Republic of Moldova is the poorest country in Europe, far behind countries like Ukraine or Albania. In the villages, 42 % of the people live in poverty, compared with 28 % in small towns and 14 % in big cities. The difficult economic situation is reflected in the environmental problems Moldavians face:

- more than 40 % of agricultural land is estimated to have degraded soils,

- water is contaminated with agrochemicals and manure,

- pesticides are a threat to humans and ecosystems,

- eutrophication affects water reservoirs, and

- climate change is expected to make extreme weather events more frequent.

Moldova is an agrarian country, but agriculture has become an extremely vulnerable sector because of the acute environmental problems, political instability and a lack of investments. The repercussions for human and economic development are severe. In 2007, a long drought reduced crop production by 70 %. The UNDP estimated the total economic loss to amount to $ 1 billion.

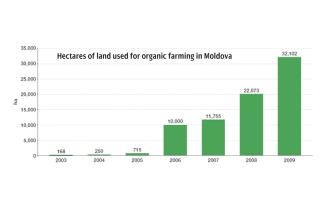

In these circumstances, it is good news that the organic sector has been growing rapidly in recent years (see graph). In 2009, organic products accounted for export revenues worth $ 48 million and made up 11 % of the country’s agricultural exports. In comparison, Ukraine, a country 20 times the size of Moldova, only ex-ported organic products worth $ 36 million that year. Most of Moldova’s organic exports go to the EU. Germany alone accounted for 12.4 % in 2009. At the same time, some 15,000 tons of organic goods were sold to Moldovan customers that year.

Today, Moldova has the most developed organic sector among the former Soviet republics according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). Commercial success, however, is the result of prudent policy and competent state action. The government is following a strategy for promoting organic agriculture and trade in organic products. Among other things, it aims to develop the domestic market and find new export markets. It hopes that some 150,000 hectares will be used for organic farming by 2020.

Public-private partnerships have made significant contributions and so has foreign aid. EcoAgriNet, for instance, was a project funded through the EU’s Joint Operational Programme Romania–Moldova–Ukraine in 2011–2012. It resulted in the creation of a cross-border network dedicated to the promotion of organic agriculture. Another relevant initiative is Farmer School, which is run in Balti by the Selectia Research Institute for Fieldcrops, the local university’s faculty of agroscience and a non-governmental organisation called AO Pro Cooperare Regionala. The idea is to provide information and expertise to young farmers who are interested in sustainable and ecological farming methods. Many of them are using their new knowledge and skills with good results.

Organic agriculture is an important option for Moldova’s impoverished rural people. It is a way of generating income while stemming environmental degradation. The related policy of the Moldovan government makes sense and further support from the European Commission is welcome. The current government’s pro-EU stance is certainly helpful.