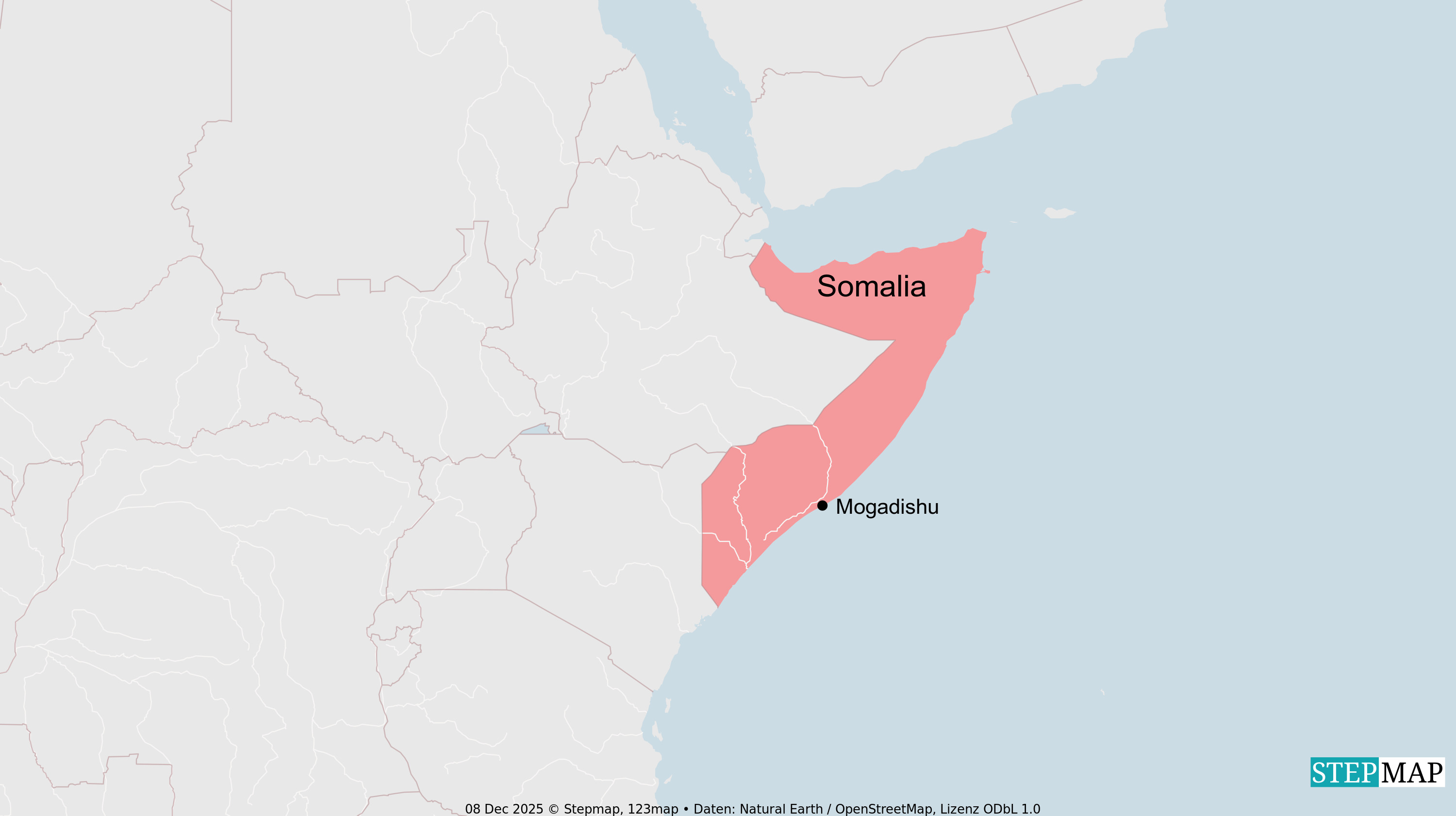

South America

A growing appeal for authoritarian rule

South America stands between two electoral super-cycles, and one trend is already emerging: The results of recent national elections in Bolivia, Chile and Argentina point to a resurgence of populism and a shift to the right. Peru, Colombia and Brazil will hold elections in 2026 and may deliver similar outcomes. Several South American countries could be on the verge of an authoritarian turn.

Why is this happening? The example of Peru illustrates the underlying dynamics at work. It shows how enduring inequalities, the deterioration of state institutions and the militarisation of politics fuel support for right-wing populism and authoritarian solutions. Peru has experienced mass protests and political agitation in recent months and will head to the polls in April.

Inequality leads to instability

Peru is a cautionary tale of how economic boom does not equal political progress. The country has had two decades of above-average growth and was invited to apply for membership in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2022. The Peruvian Sol was among South America’s strongest currencies in 2025, and the country is among the largest recipients of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Latin America.

Yet political instability remains severe. The country has had seven presidents in the last nine years. Peruvian sociologist Julio Cotler has pointed out that local elites have historically benefited from natural resource exports while keeping the gains for themselves. This dynamic has weakened state institutions and reinforced inequalities.

Peru’s crisis reflects a failure of political representation. Parliament is dominated by elites defending short-term, vested interests. Lawmakers have granted tax privileges to corporations and not regulated mining activities sufficiently, thereby enabling deforestation in the Amazon, instead of combating crime or strengthening state institutions.

Political parties are therefore increasingly seen as drivers of insecurity, corruption and impunity rather than as providers of social protection. This has fuelled widespread discontent and sparked protests, particularly among Gen Z.

Public protests used to justify the use of force

Amid growing public outrage, former president Dina Boluarte was forced to leave office in 2025, and José Jerí took over as interim president. Boluarte’s administration had failed to curb insecurity and impunity, while she faced persistent accusations of corruption. Between January and September, it is estimated that around 50 bus drivers were murdered by extortioners and armed gangs, and transport strikes repeatedly paralysed Lima. Boluarte was also never held accountable for the use of excessive force and the deaths of protesters during her rise to the presidency in 2022.

The crisis escalated in October 2025. During mass protests against Jerí’s inauguration, a rapper and street artist named Trvko was shot dead by a police officer, which sparked even more outrage. Jerí responded by declaring a state of emergency and deploying soldiers to patrol the streets to fight insecurity – despite evidence from neighbouring Ecuador that such tactics do not have the desired effects. Two years ago, Ecuador’s president announced that the country was in “internal armed conflict” and declared a state of emergency. However, the measure failed to reduce murder rates, while human-rights violations by security forces increased.

Security now dominates the political agenda. In the run-up to the 2026 election, some presidential candidates are promising “mega-jails” and even discussing the transfer of prisoners to El Salvador. Proposals include drone surveillance and expanded powers for the armed forces.

Keiko Fujimori of populist right-wing “Fuerza Popular” openly promotes “mano dura” (iron fist) policies. This rhetoric is not unique to Peru. Calls for hardline security measures are gaining traction in Colombia and beyond.

From political crisis to authoritarian revival

Peru is an example of a broader regional shift: from democratic dysfunction to authoritarian revival. Across the Andes, discontent with politics is fuelling the support for harsh measures and nostalgia for dictatorship. In Chile, supporters of recently elected José Antonio Kast have openly celebrated Augusto Pinochet’s legacy in public chants.

Yet while violence is real, security without legitimacy is ephemeral. The authoritarian turn with its calls for stronger security measures does not address the root causes of violence: inequality, institutional weakness and exclusion. Instead, it fosters a dangerous alliance between political and military elites, enabling the violent suppression of dissent in the name of order and security. Militarisation is already intensifying in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia.

As leaders across South America weaken “bloated” state institutions and increase the use of force in the name of security, they create a self-fulfilling prophecy. States become more fragile, and as studies have shown, this makes external interference more likely. If current trends continue, the Andes may see the return of a political order in which domestic and foreign elites rule through force, while demands for justice are met with repression.

Pedro Alarcón is a Global Forum Democracy and Development research fellow at the University of Cape Town. His research lies at the crossroads of climate change, energy and society, particularly in Southern Africa, Andean countries and the Philippines.

pedroalarcon76@gmail.com

Fabio Andrés Díaz Pabón is a Honorary Research Associate of the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University. His interdisciplinary research links academia and practice. He focuses on development, sustainability and conflict in Latin America and Africa.

fabioandres.diazpabon@uct.ac.za