Authoritarian regimes

“Humour helps overcome the fear imposed by dictatorship”

Mana Neyestani interviewed by Eva-Maria Verfürth

Mana Neyestani’s life has not always gone as he would have wished: One of his children’s cartoons sparked uprisings in Iran in 2006 and he was sent to the notorious Evin prison. After three months in custody, he fled Iran and travelled via Malaysia to France, where he was granted asylum. He continues to draw cartoons about life in Iran, but also about exile and migration. Social media helps him disseminate his cartoons in his home country and worldwide. Almost one million people follow him on Instagram.

Mana, you once said that you’re not a genuinely political person. Yet you’re one of the most famous Iranian political cartoonists. How did you become a political artist?

It’s true that I prefer to follow cultural and cinematic news. However, living in a country like Iran inevitably makes you political. The country is controlled by a totalitarian religious regime that interferes with every aspect of private life. I believe the most fundamental role of an artist, even the least political one, is to think freely. But in a dictatorship, especially a religious one, thinking freely is itself a crime and a form of political resistance.

You’re living in France at the moment, but your art hasn’t become any less political.

Over time, I have realised that even living in developed, free and democratic countries does not eliminate the need to be politically aware. Democracy is fragile and must be defended every day.

You were a cartoonist in a country with a repressive regime, and now you’re a refugee in a foreign country. Does the Iranian regime’s censorship still affect you?

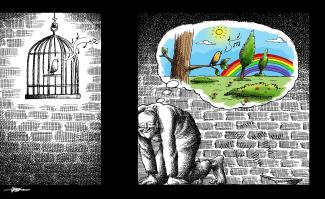

In Iran, the regime was the primary enforcer of censorship and repression. When I started my career in Iran, it was not possible to draw political cartoons as openly and directly as cartoonists publishing in Western media do. Much of my work relied on symbolism and metaphor. Today, I still draw about issues related to Iran. However, the mechanisms of pressure and censorship have become more complex. Now, the Iranian regime’s cyber army and various online groups use coordinated attacks, character assassination, harassment and intimidation to silence opinions they dislike.

You deal with deeply distressing issues such as repression, violence and censorship. What is the role of humour in the face of oppression?

Humour makes it slightly easier to digest harsh realities. It is also a psychological tool to overcome the fear imposed by dictatorship and repression. With humour, it is easy to dismantle false sanctities and break the illusion of grandeur.

Are there any red lines or subjects you wouldn’t touch in a cartoon?

I try not to let red lines dictate my work. However, growing up in a country with numerous strict red lines has inevitably ingrained some of these taboos in my subconscious. Self-censorship is not something one can easily overcome. Religion, especially the sacred aspects of Islam, remains the biggest red line. The most obvious reason is what happened to the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo in the heart of Paris, the so-called cradle of democracy.

You have experienced how explosive a simple cartoon can become, that it can be interpreted in a very different way than originally intended: Your children’s cartoon about a cockroach caused controversy and even sparked uproar among the Azeri population in Iran. Has this experience changed the way you work? Have you become more cautious, for example?

It has certainly affected my subconscious. But the issue is that if we try to account for the sensitivities of various social groups and predict their reactions, which is impossible, there will be very little left to satirise, and cartoonists will become paralysed.

The internet is censored in Iran. How can you reach people over there, and what feedback do they give you?

People inside Iran use VPNs and other circumvention tools to visit my Instagram and other social-media platforms. They leave comments and sometimes send direct messages. Some agree with my work, while others do not. Naturally, supporters of the Iranian government are not happy with my cartoons.

Are you in contact with other satirists from Iran?

Yes, through social media. Unfortunately, cartoonists inside Iran are in a very difficult situation – not only because of security concerns and a lack of freedom of expression, but also because of economic hardship. As a result, many of Iran’s most talented cartoonists have shifted to more financially viable fields such as advertising.

It wasn’t easy for you to reach Europe. After escaping from Iran to Malaysia, you were still in danger of being deported back to Iran. With the support of Reporters Without Borders, you were able to move to France, where you are now a member of ICORN, the International Cities of Refuge Network. How can international cooperation and NGOs support persecuted satirists?

This is not an easy question. Helping at-risk cartoonists and satirists – like other persecuted individuals – should primarily be the responsibility of western governments, as they have the power to issue visas and grant asylum. The effectiveness of NGOs depends on their influence over these governments. ICORN is one of the more effective organisations because it works closely with the administrations of major cities.

Mana Neyestani is a cartoonist from Iran.

Instagram: @neyestanimana