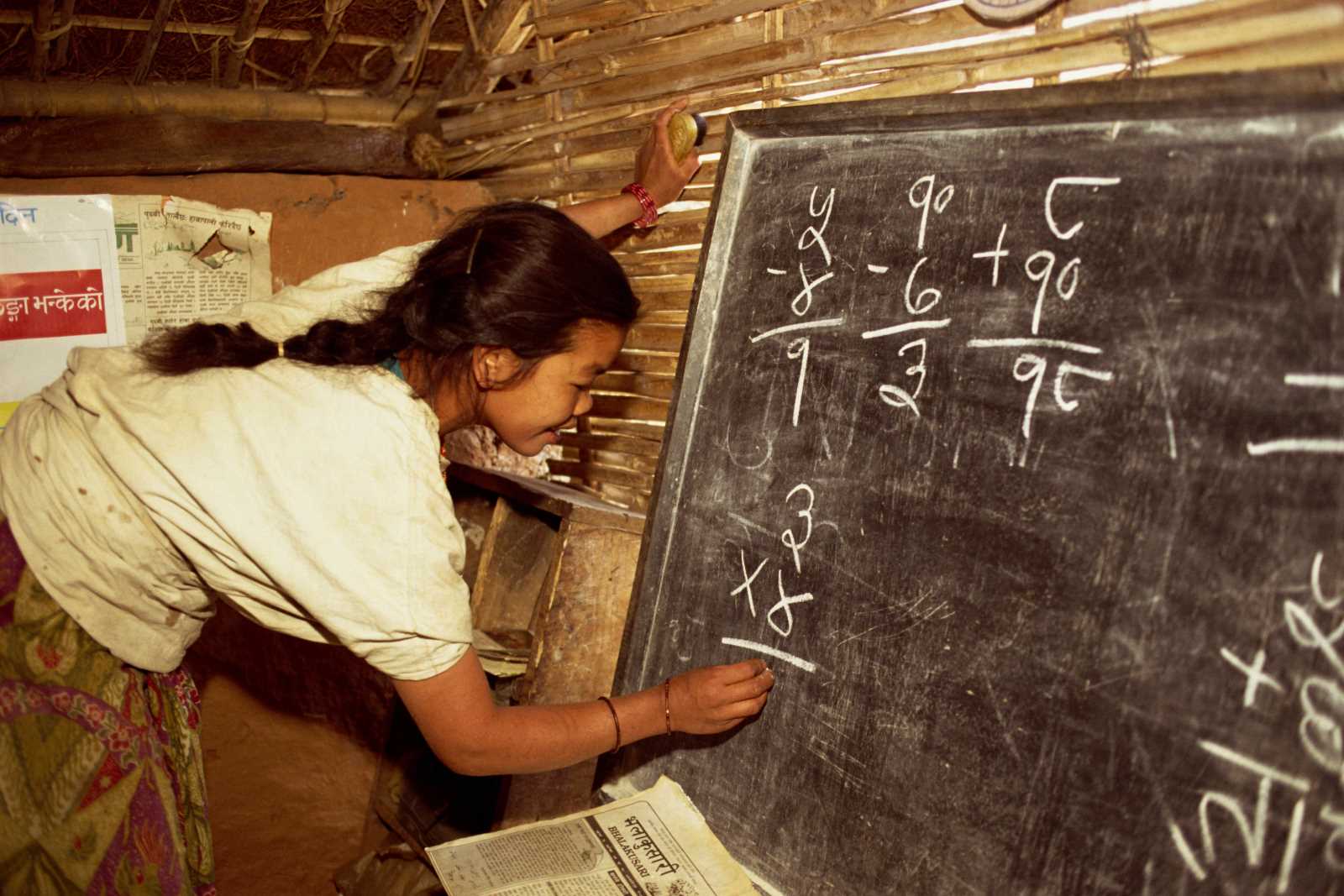

Girl's education

Nepalese girls still don’t have equal educational opportunities

UNESCO estimates that 129 million girls are out of school worldwide – 32 million of primary school age and 97 million who would actually go to secondary school. Conflict, poverty, child labour, child marriage, gender-based violence and the multiple consequences of Covid-19 are some of the barriers that keep girls out of school.

Nepal is one of the countries that pushes these numbers up. In addition to the reasons mentioned above, several socio-cultural factors stop Nepali girls from going to school.

Nepalese society is dominated by men. Families prefer sons over daughters. This preference is deeply rooted in traditional gender roles, customs and expectations. Many Nepalese believe that only boys can carry on their father’s name and continue the family lineage.

Daughters, conversely, are considered to be a burden. They are not even taken for a real part of their family of origin because they are going to be sent off to live with their groom’s family anyway – and parents will need to pay dowry for them and bring gifts for their in-laws. Therefore, families are less interested in investing in their daughters’ education. The situation is likely to be worse if a girl’s family is economically poor, marginalized or from a rural community.

Constitutional guarantees

Nepalese law contrasts with these realities. It actually obliges parents to send their children to school – education (see box) is compulsory for every child between four and thirteen years. In fact, the 2015 constitution guarantees every citizen the right to free education up to the secondary level. This means that parents do not have to pay school fees if they send their children to state-run public schools.

For children with disabilities and children from economically indigent families, the state also provides free higher education. Visually impaired children and those with a hearing or speaking impairment receive free lessons using braille script or sign language. The constitution also guarantees lessons in the respective local language.

Women’s rights are also anchored in the constitution: it states that they have the right to seize special opportunities in health, employment, social security – and education. Until now, this has usually meant having a certain quota. For example, 33 % of the members of parliament must be female, and in higher education 33 % of university places are allocated to women.

A matter of class

There are two types of schools in Nepal: public schools, which are funded by the government and therefore free of charge; and private schools, which are non-governmental and for-profit. In general, only people from the upper middle or higher classes can afford to send their children to well-equipped private schools.

Therefore, public schools became synonymous with schools for the lower class and poor people. The quality of public schools is seriously affected by the lack of resources such as reading materials. They are located across the country, while private schools are largely centered in cities. Lower middle class or middle class families tend to send their daughters to public schools, while sons visit private schools.

Many public schools lack proper toilets and sanitation. This severely affects girls who are menstruating. In rural Nepal, sanitation facilities are often insufficient, so girls generally miss at least four days of school every month. In addition, particularly in the western parts of the country, women are treated as impure and untouchable while they are menstruating. Here, the Chhaupadi tradition is practiced, which prohibits Hindu women from participating in family activities during their menstruation. They are not allowed to stay in the family house while on their period and are instead required to live in a Chhau Goth, a cattle shed or menstruation hut.

The Covid-19 pandemic and post-pandemic situation worsened the circumstances for girls. As the financial situation of many families became ever more dire, parents prioritised the boys again and discontinued only their daughters’ education. As more girls are now out of school, they are more likely to become victims of child marriage, trafficking or child labour.

The Nepalese government has launched some initiatives and campaigns to improve girls’ education. For instance, in the Madhesh province, the chief minister’s office started a campaign called “Beti Bachau – Beti Padhau” (“Save Daughters, Educate Daughters”) in 2019, inspired by similar campaigns in India. Through this campaign, every newborn girl is supposed to be insured and to receive approximately $ 950 for her education after she gets her citizenship certificates. Moreover, bicycles have been distributed to young girls.

Corrupted initiatives

What’s more, the aim of this campaign was to discourage sex selective abortion and curb child marriage as well as the existing dowry system in Madhesh. It was well received by the general public. However, in August 2022, an anti-graft body – the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority – filed a corruption case against six people including the then Secretary of Madhesh Province at the Special Court in Kathmandu. They are accused of carrying out financially illegal activities amounting to approximately $ 780,000 in the name of the campaign: they allegedly bought low-quality bicycles, which they then distributed and charged for as high-value bikes. The case is still pending before the court. It shows that rampant corruption also affects initiatives taken for the improvement of girls’ education in Nepal.

The serious distortion in the Nepalese education system is obvious. Despite the legally guaranteed free basic education, by far not all children go to school. And despite all legal guarantees for equality and non-discrimination, girls and women definitely do not have the same educational opportunities compared to boys and men. Gender differences and inequalities in Nepal indisputably persist.

Lastly it is important to note that educating girls is not only about sending them to school. It is about giving them skills, capacities and the confidence to be independent so that they have the power to make decisions about their lives and change society. It is all about empowerment, but that empowerment starts with sending them to school and allowing them to stay there.

Rukamanee Maharjan is an assistant professor of law at Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu.

rukumaharjan@gmail.com