Demographic change

Progress may not be sustained

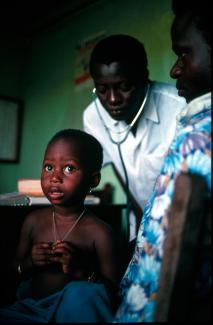

In Benin, the average life expectancy has increased from 37 years in 1960 to more than 60 years today. However, there are still big discrepancies between urban and rural areas. In the big urban agglomerations of Cotonou and in smaller towns like Porto Novo, Ouidah or Parakou basic social-service infrastructure exists, including hospitals, laboratories for clinical tests or pharmacies. During immunisation campaigns, many people are vaccinated free of charge. Maternity clinics ensure that babies are also provided with free immunisation.

People living in villages are disadvantaged, however, especially in the remote areas of the north. They are generally denied access to the most basic health services. Women there often give birth at home, which increases the risks of death for both mother and baby.

In 2015, 405 women died per 100,000 live births, according to UN data. In comparison, the maternal death rate was 576 in 1990. Of 1,000 babies, 65 died in 2015. The figure for 1990 was 107. On average, women still have 4.6 children, two fewer than in 1990, World Bank statistics show.

According to UN, about three quarters of the people had access to safe drinking water from an improved source in 2008, but only 12 % had access to improved sanitation. This is worrisome since safe drinking-water supply cannot be guaranteed in the long run if sanitation stays poor.

Making matters worse, only very few medical doctors are prepared to serve in villages that lack electric power and safe water supply. Moreover, non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes or and hypertension are hard to diagnose in places that lack modern technology and specialists. In rural areas, antibiotics and other life-sustaining drugs are not always available. In the cities, poor people may be unable to afford them.

On the other hand, some trends have been promising in past decades. Yellow fever has almost been eradicated. Meningitis has become rare. The prevalence of two tropical diseases, sleeping sickness and yaws, has been reduced considerably. Mobile health clinics have been making a difference even in rural areas.

Statistics in Africa are not always reliable however. They may not reflect the whole picture. It is bewildering that the number of graveyards seems to be multiplying, and masses of caskets are on sale by the roadside. Sometimes it looks like most urban people in Cotonou, Porto Novo and other towns spend their weekends burying their dead. This impression may be a consequence of population growth. Benin has more than 11 million people today – almost twice as many as in 1995. The cities have grown in particular, so more deaths need not be a sign of worsening living conditions.

On the other hand, poverty has recently been becoming worse, and that may have an impact on life expectancy. Many people lack sufficient resources to adequately feed themselves and access appropriate health-care services.

According to a UN Development Programme report of 2014, monetary poverty has increased in Benin, and progress in health-care delivery and education was not enough to sustain higher life expectancy in the long run. In other words, the progress made did not look good enough in the eyes of the UNDP.

The World Bank paints a similar picture of Benin. It reports that poverty is on the rise in spite of moderate annual GDP growth rates of four to five percent over the past two decades. The national poverty rate, according to its data, was 35 % in 2009 and 40 % in 2015.

Part of the problem is that the informal sector makes up about two thirds of the economy, employing more than 90 % of the work force, according to the World Bank (also see my essay in D+C/E+Z e-Paper 2017/11, p. 16). “Benin’s economy relies heavily on its informal re-export and transit trade to Nigeria, which makes up roughly 20 %,” the Bank states. To fight poverty in a sustainable way, Benin’s economy must modernise.

Karim Okanla is a media scholar and free-lance writer from Benin.

karimokanla@yahoo.com