Landlocked nation

Nepal is sandwiched between two BRICS members

Nepal is a small Himalayan nation of about 30 million people. Its two giant neighbours each have 1.4 billion people, and both are keen on expanding their global influence. Though India and China are members of the loose alliance BRICS+ (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa plus several newly admitted countries), they are also rivals who want to shape their neighbourhood.

Nepal has friendly relations with both, and that is evident in cooperation at various levels. The government of Nepal describes the ties as “age old and deeply rooted”. However, the constant frictions between China and India cast a long shadow, influencing every aspect of life in Nepal.

India is Nepal’s most important trade partner, and China is the second most important one. In both cases, Nepal is running huge trade deficits. Nepal imports different kinds of manufactured goods, including high-tech items, as well as energy and some staple foods. Its exports consist of agricultural products and handicrafts. It is a constant challenge to reduce imports and expand exports.

Cultural affinity

The links Nepalis have to India are quite different from the ones they have to China. In terms of language and culture, Nepal and India are actually quite similar. In both countries, roughly 80 % of the people are Hindus, moreover. The shared border is 1850 km long and open. Masses of people regularly cross it in either direction. Nepalis migrate to India for job opportunities and education, with many working in low-skill sectors like construction or agriculture. Significant numbers – mostly men – go to India for seasonal work. However, Indians also come to Nepal for work in sectors like construction and agriculture.

By contrast, Chinese culture and language are very different. The 1400 km border runs through largely inaccessible mountains. There is far less migration. Nepalis go to China primarily for higher education or specialised work opportunities. To some extent, Chinese investment projects are creating such opportunities. In everyday life, Nepalis thus feel closer to India.

Questions of ideology

The two neighbours are also quite different in terms of ideology and governance. China is a Communist one-party state, whereas India is multi-party democracy with an independent judiciary and elected sub-national authorities that have considerable autonomy.

Nepal used to be a monarchy with a Hindu king. In 2008, however, it became a republic, and the constitution of 2015 defined it as secular democracy. The political system thus resembles India’s more than China’s.

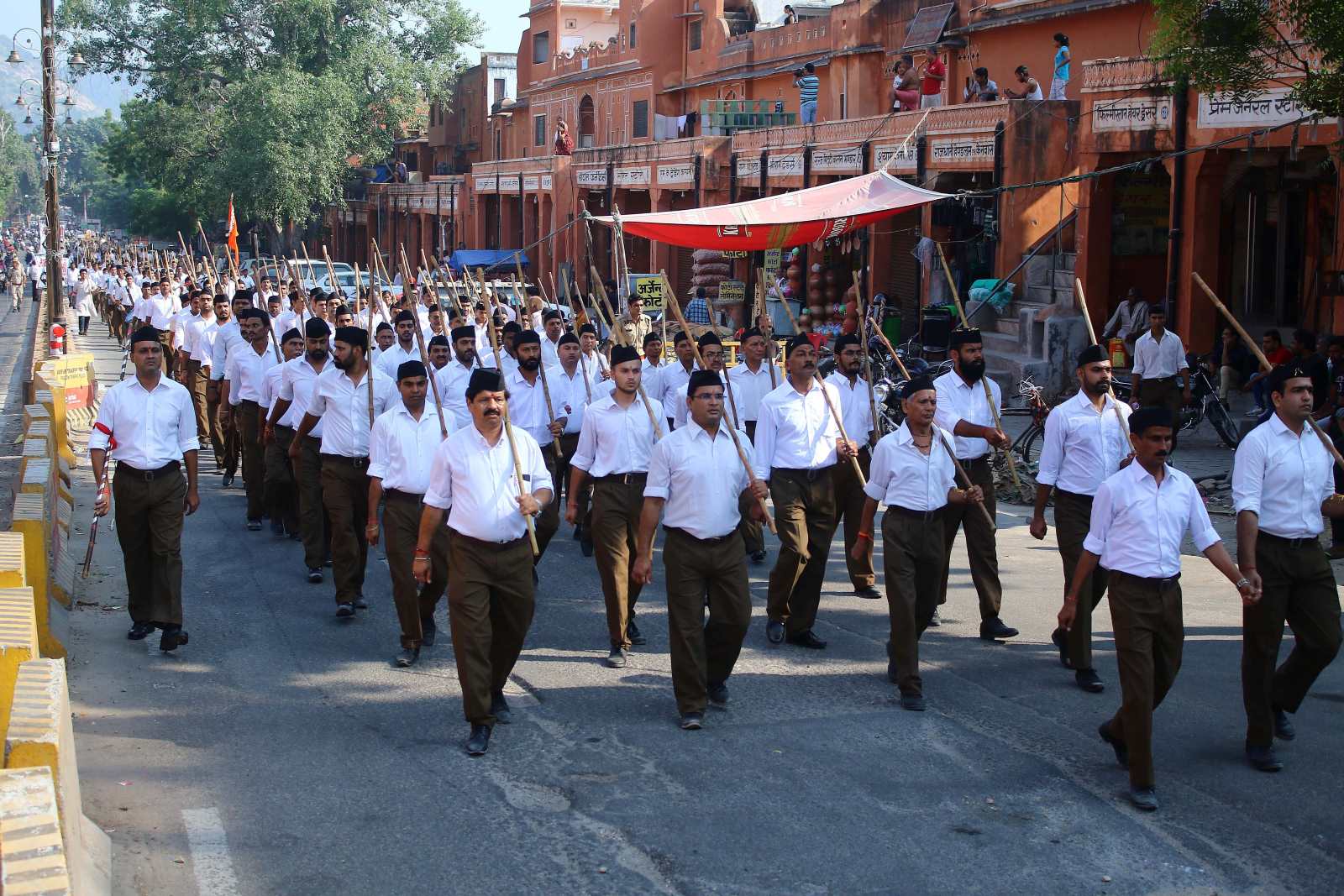

India’s domestic politics also affect Nepal more. An important reason is that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is currently running for office in another general election, has politicised the Hindu religion. His party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has a long history of aggressive identity politics, and it is worrisome that its Hindu-supremacism is encouraging extremists in Nepal.

Indeed, Nepal has a royalist party, the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, which wants the country to abandon secularism and become a Hindu state. Nepali Hindu-supremacists, moreover, have been attacking people of other faiths, accusing them of forcing Hindus to convert to their respective religions. These things are seen to result from Indian influence in one way or another.

On the other hand, it is widely believed that Nepal’s Communist parties, which are quite important, receive financial and ideological support from China. So far, however, the Communists have accepted Nepal’s multi-party system and have been playing a mostly constructive role within it.

The presence of Tibetan refugees in Nepal, however, is a sensitive issue. China seems to want to restrict their activities. Indeed, Buddhists from Tibet are not allowed to celebrate the birthday of the Dalai Lama, their spiritual leader, in public in Nepal. It is widely thought that the authorities have taken this course to please Beijing. The Dalai Lama fled to India when China invaded and annexed his country in 1959 and has since been leading a government in exile.

Border disputes

China, India and Nepal have some contentions regarding borders. The Lipulekh Pass is the most important route from the South-Asian subcontinent to Tibet. Both India and Nepal lay claim to the pass and the surrounding Kalpani area. Though Nepal considers it part of its sovereign territory, it is administered by the Indian state of Uttarakhand.

Lipulekh matters in Sino-Indian relationships. The pass has been mentioned in several agreements. For example, the 2015 Sino-Indian pact considers it to be the tri-junction between Nepal, India and China. The pact was concluded without either party consulting Nepal.

At the same time, China and India also have border disputes. Both maintain a significant military presence in the mountains. Occasional border clashes pose a threat to Nepal’s territorial integrity.

Development cooperation

Both China and India provide development assistance to Nepal. Early on, from 1951 to 1954, India supported the construction of the airport in Kathmandu. That was the beginning of Nepal’s and India’s partnership. India has since assisted various other infrastructure projects, provided humanitarian relief after natural disasters and invested in community development. India has also donated ambulances, school buses and election vehicles. Indian aid generally comes in the form of grants.

For Nepal as a landlocked country, robust cross-border infrastructure is very important. It is a prerequisite for economic growth. The links to India are quite good. They include railway connections, roads and fibre links. There even is a cross-border petroleum pipeline as well as cooperation on hydropower. Indian investments were essential for building these links.

China provides three types of assistance, namely, grants (aid gratis), interest-free loans and concessional loans with subsidised interest rates. China has helped to improve roads, construct the Pokhara International Airport, build hydropower facilities and restore border bridges.

Seven years ago, Nepal became a partner of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The related documents are not available to the public, so the terms of cooperation with China remain not transparent. Some observers warn of potential debt traps.

Not least because of the high mountain range, cross-border infrastructure is weaker in the North. As trade with China is growing, connectivity is becoming increasingly important, and the BRI may yet make a difference.

All summed up, Nepal maintains friendly relationships with both neighbouring giants, but the situation is not easy. Nepal must cope with trade imbalances, manage border disputes and prevent disruptive foreign interference. So far, Nepal has been able to maintain a neutral stance, cooperating with both China and India, but not alienating either of them. That they both belong to the BRICS+ is hardly relevant to Nepal’s diplomacy. Seen from Kathmandu, the two giants seem to compete fiercely with one another and certainly do not look closely aligned.

Rukamanee Maharjan is an assistant professor of law at Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu.

rukamanee.maharjan@nlc.tu.edu.np