Biodiversity

A town in Mexico shows how communities can save reefs

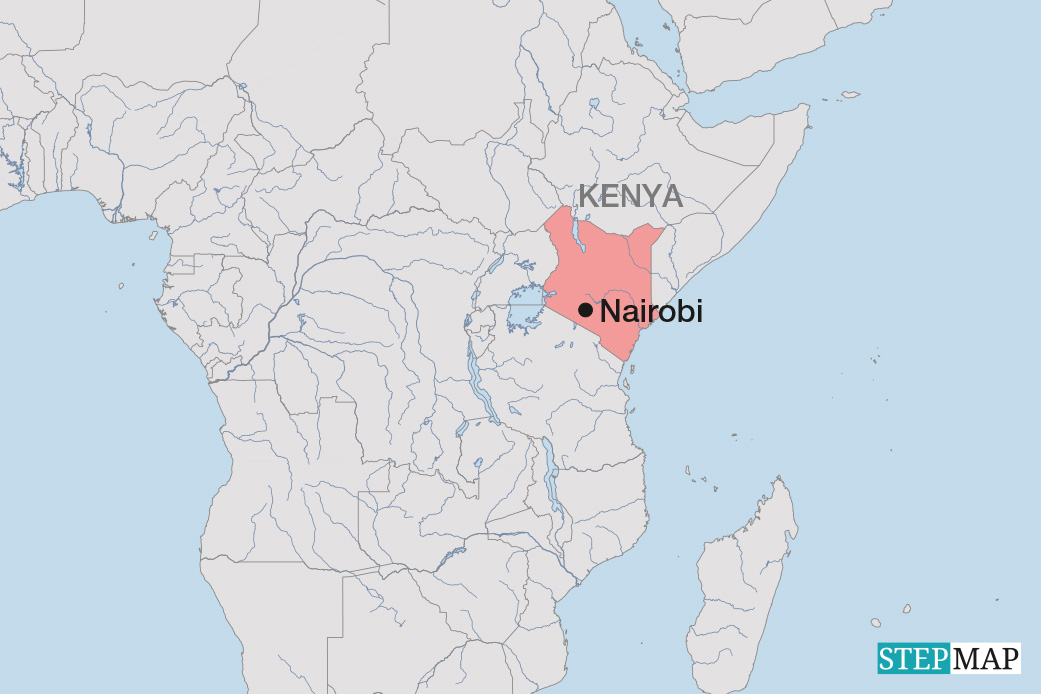

Early in the morning, boats head out at Cabo Pulmo, a small town on the eastern coast of the Baja California Peninsula. They look different today than they did years ago. Instead of loading fishing nets, they are prepared for tourists and divers. The community in Cabo Pulmo once depended entirely on fishing but now has been protecting its reef since more than 30 years, showing how conservation can be successful when local people take the lead.

Marine reefs are nurseries for ocean life, offering food and shelter to species ranging from colourful reef fish to sharks. They protect coasts from storms, sustain small-scale fishing and attract millions of tourists. In Mexico, snorkelling and diving generate between $ 455 and $ 725 million annually, a study published in 2021 found.

Mexico faces a persistent challenge

But reefs in the Gulf of California have been in steep decline. Long-term studies by scientist Carlos Sánchez of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur show that already back in 2015, more than 68 % of the reefs were in a degraded state. Today, more than 90 % are degraded, driven by decades of overfishing and, more recently, marine heatwaves linked to climate change.

To track the health of reefs in the Gulf of California, Sánchez and his team established the Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program (LTEMP) in 1998. Since then, the team has surveyed hundreds of sites, documenting the distribution of more than 470 fish and invertebrate species. By measuring composition, density, biomass and trophic levels, the programme has created a robust baseline for understanding how marine communities change over time.

These insights guide conservation strategies for recovery potential. And yet, Mexico faces a persistent challenge: While Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are a main tool for conservation, most of them remain so called “paper parks”: reserves that exist on maps but lack funding and enforcement.

A reef turns into a shared heritage

Cabo Pulmo is one of the few exceptions. In 1995, residents agreed to stop fishing. Consequently, between 1999 and 2009, the total fish biomass increased by 463 %. Today, 100 % of the Cabo Pulmo National Park are under strict no-take protection.

The shift was not easy. Families lost income and traditions, recalls Angélica Tamayo, a marine biologist and fisherman’s daughter. “It was hard at first, but as the reef was collapsing, the community chose its conservation.” Over time, former fishers became dive guides and eco-tourism operators. The reef turned from a source of extraction into a shared heritage.

But success has also brought challenges. Rising tourist numbers put pressure on the reef and the community. “We need strict rules to ensure that wildlife is not disturbed,” says Tamayo, emphasising that sustainable tourism depends on respect for the ecosystem. Sánchez agrees, adding that if profits from tourism go mainly to outside investors, local support could weaken. Conservation only lasts if communities are both guardians and beneficiaries. The reef stands as rare proof in the Gulf of California that recovery is possible when conservation and livelihoods move together.

Pamela Cruz is the Director at La Playa Centro Comunitario, a community centre in Baja Sur, and Strategic Advisor at MY World Mexico.

pamela.cruzm@gmail.com