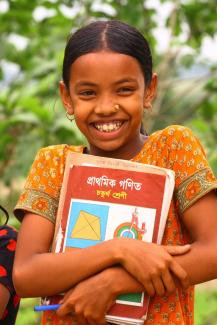

Education

Marriage instead of graduation

In Bangladesh in 2010, 97 % of the girls aged six to 10 went to primary school, according to official statistics, and so did 92 % of the boys. Moreover, the government data indicate that 55 % of girls aged 11 to 15 were enrolled in secondary schools, as were 45 % of boys.

Government data are sometimes distorted, but the general trend in Bangladesh is undisputed. We contributed to a nationwide study on “Women’s life choices and attitudes” (WilCAS) in 2014. Our survey relied on information provided by mothers rather than on data provided by schools. According to our assessment, the girls’ net enrolment rates were 83 % in primary education and 58 % in secondary education in 2014. The respective shares for boys were 81 % and 47 %. These figures are less impressive than the government statistics, but are nonetheless very good given that Bangladesh is a very poor country. Only two decades ago, girls’ enrolment was lower than boys. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen has repeatedly stressed that India and other countries should learn from Bangladesh’s educational success.

That said, the risk of dropping out of school remains considerable. Our estimate is that 32 % of the boys and 24 % of the girls who went to primary school in 2010 had stopped going to (secondary) school by 2014. Apparently, the risk of dropping out increases with the girls’ age. According to our sample, more than half of the girls left school for “marriage-related reasons”. That was the case for only one fifth of the male drop-outs.

In previous decades, early marriage was even more likely to disrupt women’s education. The WiLCAS data show that almost two thirds of all drop-outs among the mothers surveyed had quit school because they got married.

It is telling, moreover, that “household poverty” is the second most important reason for leaving school today. It means that families cannot afford school-related expenses. This trend is not unusual. According to a study published by UNESCO and UNICEF (2015), “in many countries, low-income households cannot afford the direct costs of sending their children to school (for instance for fees, uniforms or books) or the indirect costs resulting from the lost wages or household contributions of their sons and daughters.”

In Bangladesh, the trend is nonetheless puzzling because the government has been promoting girls’ enrolment in schools since the 1990s and has lowered the costs of school attendance in several ways. Moreover, income poverty has been declining. Most likely, the reference to household poverty actually indicates a still prevalent anti-girl bias at the household level.

It is useful to consider what households spend on children’s schooling. At the primary level, total educational expenditure for boys and girls is almost equal. In fact, slightly more is spent on girls, though spending on private-tuition is slightly higher for boys. The expenditure for boys in secondary schools exceeds that for girls by 27 % however, and families invest 38 % more in boys’ private tuition at that level.

It is a sad truth that private tuition is becoming increasingly important even in rural areas. This trend is evident across South Asia (see D+C/E+Z e-Paper 2016/06, p. 36 f., and e-Paper 2016/02, p. 11). The main reason is the dismal quality of state-run schools. According to an independent assessment of student learning in rural Bangladesh by Asadullah and Chaudhury (2015), there is a weak relationship between learning outcomes and years spent in schools.

Our data indicate that Bangladeshi parents value the education of their sons and daughters equally as far as primary schooling is concerned. However, there is a serious gender gap in secondary schooling, even though that is not evident in the enrolment figures. Families invest less in girls’ education, though they send them to school. Girls’ chances of actually obtaining the standard school certificate after class 10 are smaller than those of boys.

Most likely, the expectation of early marriage is the primary factor behind the gender disparity in household expenditures. If the norm is that adolescent girls marry instead of finishing school, investing in their education becomes a luxury impoverished parents cannot afford. That they are expected to pay a substantial dowry when their daughter gets married is a further disincentive to investing in education. In turn, this means that households are too poor to invest in girls’ education.

The good news is that traditional factors such as the lack of schools within commuting distance and religious opposition to female schooling are no longer holding back Bangladeshi girls. The bad news is that girls still lack equal opportunities in education. What the country now needs is a new policy to help girls finish secondary school.

Niaz Asadullah is the deputy director of the Centre for Poverty and Development Studies (CPDS) at the University of Malaya.

m.niaz@um.edu.my

Zaki Wahhaj is senior lecturer in Economics at the University of Kent.

z.wahhaj@kent.ac.uk

Links

UNESCO and UNICEF, 2015: Child labour and out-of-school children: evidence from 25 developing countries.

http://allinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/OOSC-2014-Child-labour-final.pdf

Asadullah, M. N., and Chaudhury, N., 2015: The dissonance between schooling and learning: evidence from rural Bangladesh. Comparative Education Review 59, no. 3.

http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/681929?journalCode=cer

WiLCAS, 2014: Women’s live choices and attitudes survey.

http://www.integgra.org/