Environmental health

Why some Indian farmers are backing away from rice cultivation

Ramranjan Ghosh is a marginal farmer in the Indian state of West Bengal. He cultivates rice and seasonal vegetables on his ancestral land. He used to harvest rice twice every year, but in 2022, his family stopped growing summer rice. Ramranjan must now feed his family from the rice he grows in the monsoon season and free food grains provided by the government.

This is not an isolated story. Many marginal farmers and sharecroppers in the Birbhum District are suffering hardship. Ramranjan says that the “high cost of electricity, chemical fertiliser and pesticides” are one reason, while “low market prices” are the other.

The problem, however, runs deeper. To understand the issue, one needs to know the history of agricultural development in the past 40 years.

Before the green revolution that began in late 1960s, paddy farming in Ramranjan’s village was done with water from the ravine and its underground springs. Later, four big water tanks were built to support the cultivation of vegetables and various winter crops that do not need much water.

High-yielding variety

The green revolution had a massive impact. The high-yielding variety of rice was introduced in the 1980s, which is locally called “Boro”. The irrigation system was improved, because this variety needs much water. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, rice production increased immensely, not only in West Bengal.

The high-yielding variety is grown in the summer. The state government allowed farmers to extract groundwater for this purpose. Boro production helped to improve both food security and the employment situation. Indeed, seasonal labour migration started from the poorer neighbouring state.

As farmers grew more rice, they began to abandon traditional crops such as wheat, pulses, mustard and vegetables. Private-sector companies began selling more high-yielding seed, which increasingly displaced traditional varieties that farmers could breed by keeping part of the harvest for the next planting season. Farms became dependent on buying seed year after year. The same companies, moreover, provided pesticides to keep a check on rice beetles that would otherwise have thrived on the new variety of rice.

Over the years, farmers’ dependency on companies and their products increased. Labour migration intensified too, with buses and even trains moving workers around. Wealthy farmers stopped using bullock ploughs. They bought tractors with bank loans. Barren fields and lowlands, which had been used for livestock grazing, were converted into agricultural fields.

A golden time for farmers

It was a golden time of farmers, and it went on for more than two decades. Eventually, it became obvious that the overextraction of ground water and the use of chemical fertilisers were detrimental to the environment. In some areas, moreover, arsenic was found in deep tube wells that were used for drinking water. The state government began to peddle back from supporting rice mono-cropping.

The climate crisis is compounding problems. Summers are becoming longer, and the rain is increasingly irregular. Both phenomena have impacts on the ponds as well as on the ravine and its springs. Ramranjan and his neighbours sometimes run out of irrigation water. Moreover, the use of tractors has made the soil hard, while chemical fertilisers have depleted its natural fertility. Chemicals, moreover, killed various types of beneficial earthworms. Their eco-system service consists of stabilising the soil structure and providing nutrients.

Economically disadvantaged and marginalised people, including, for instance, Adivasi villages, are affected in other ways too. They traditionally depended on naturally available food such as small fishes and snails from local water bodies as well as wild vegetables that grew in the ravine and the lowlands. These resources are not abundantly available anymore.

Costs and revenues

Farmers must pay increasingly higher prices for farm inputs as well as for irrigation water and migrant workers. The prices rice harvests fetch have not been rising at the same rate. Accordingly, rice cultivation looks less and less attractive in plain business terms.

Things are particularly difficult for sharecroppers who grow rice on leased fields. A state law regulates what share of the harvest they owe the landowner. It is based on the assumption that sharecroppers do not spend much money on inputs, for example, because they use manure to fertilise the fields. They hardly do so anymore, but while their share of the harvest has not changed, they alone bear the rising costs of inputs.

The state government is supporting farmers in various ways. They get a compensation when extreme weather makes crops fail. They are also encouraged to use composted manure to restore the soil’s natural health. The government recommends starting fruit orchards or to cultivate lentils in order to generate less water-intensive incomes. In Ramranjan’s village, however, lentil cultivation proved disappointing due to poor soil quality.

Some farmers are now testing various alternatives to high-yielding rice on small plots. Non-governmental organisations are involved in such efforts too. Reliance on natural fertilisers is a top concern. Social enterprises like Dularia are raising awareness for eco-friendly farming in the district.

Such activities are making a difference. Farmers have several options, but many find it hard to give up – or merely reduce – rice farming. Experience shows, however, that mono-cropping makes them vulnerable. Wheat, millet, maize, sesame, finger millet and mustard can be grown with comparatively little water, and the crops fetch stable and high prices in markets.

Orchard farming can be profitable too. In order to stem erosion, it makes sense to plant mango, papaya or banana trees on the slopes of the ravine and the banks of ponds. It can be economically attractive to rear chicken, ducks, goats or pigs. Projects can be launched and run on small budgets.

The government can do still more to help, however. It should give even more advice on what climate change will mean – and how best to adapt.

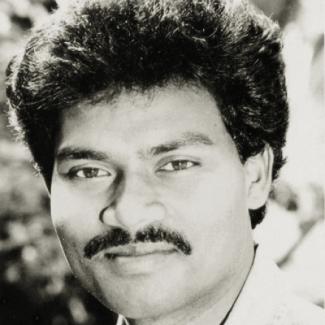

Boro Baski works for the community-based organisation Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha in West Bengal. It is supported by the German NGO Freundeskreis Ghosaldanga und Bishnubati.

borobaski@gmail.com

http://www.dorfentwicklung-indien.de