Tourism for development

Live elephants have to be worth more

Tourism is a major contributor to the national economies in sub-Sahara Africa today. The huge potential of nature-based tourism constantly inspires new projects. Exciting results are expected from approaches which combine wildlife conservation and poverty reduction.

The KAZA Transfrontier Conservation Area is such an example. It was established in 2011 by the governments of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. It links up more than 20 national parks, nature reserves, conservancies and areas of sustainable use. This transborder conservation area is one-and-a-half times the size of Germany. Around 70 % of the area is conserved or sustainably used, which significantly benefits biodiversity in the region.

Some of the conservation areas in KAZA are home to around 250,000 elephants, which is half of Africa’s total elephant population. However, there are too many pachyderms in just a few national parks in northern Botswana and Zimbabwe and none in many others. Hence, the biodiversity in these places suffers as a result of the elephants’ enormous appetite. The establishment of migratory wildlife corridors between these parks and other conservation areas will allow the elephants and other wildlife species to move back into their former expansion range and reduce the pressure on the overpopulated parks.

KAZA is also populated by around 2.6 million people, the majority of whom are subsistence farmers. For them, elephants are an existential threat because they trample their maize fields and destroy houses. Violent encounters that cost elephant and even human lives occur time and time again. In such circumstances it is difficult to speak of poverty reduction.

Unsurprisingly, some local residents collaborate with poachers and engage in the illegal ivory trade in order to supplement their low incomes. To turn the tables around, one of the main goals of the KAZA project – which is supported by Worldwide Fund For Nature (WWF) and other partners – is to generate income for local people from sustainable wildlife tourism and hence reduce the illegal activities.

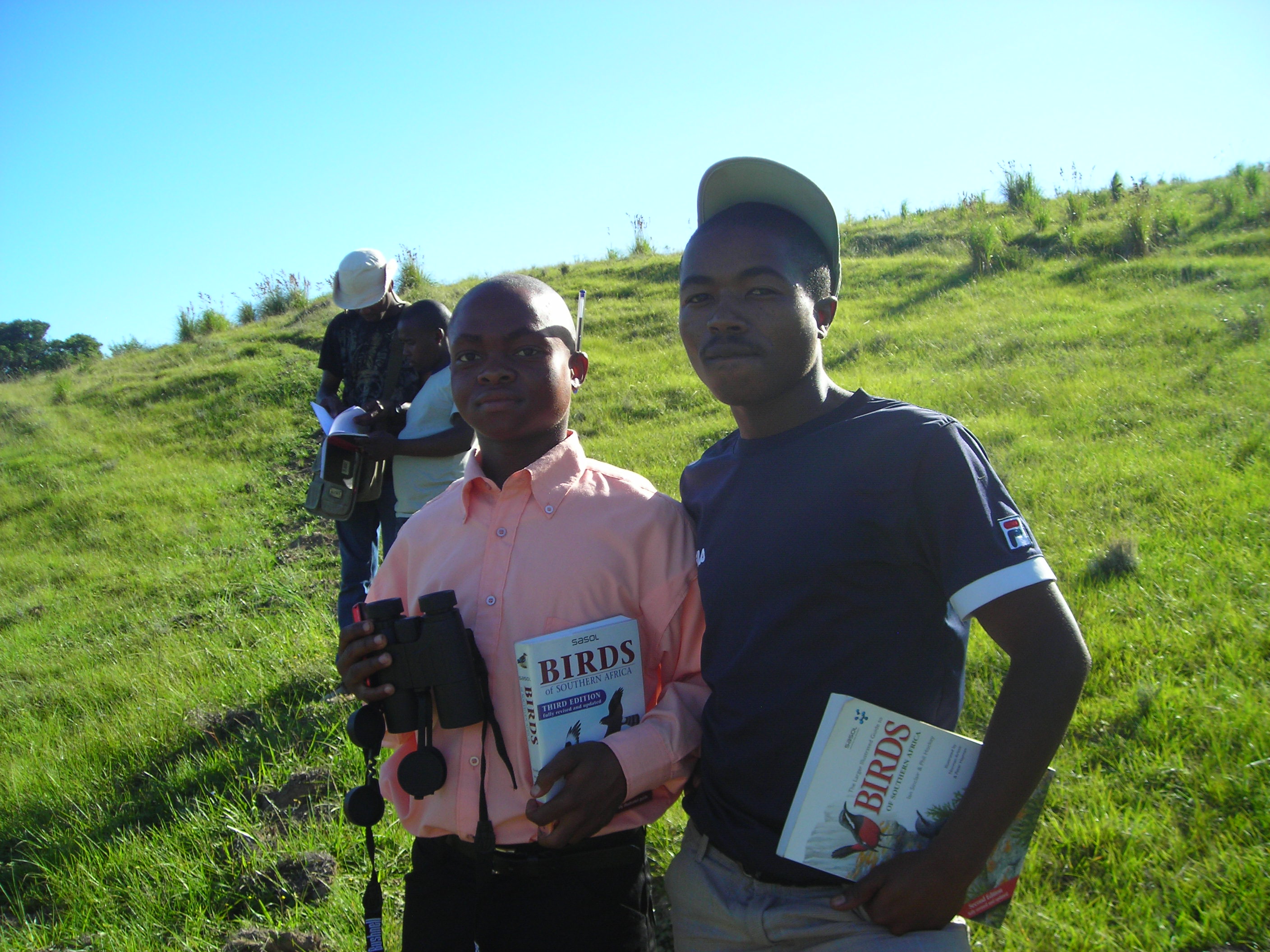

In this context, the concept of community conservancies has proven to be successful. The concept is based on the assumption that people protect what they benefit from. If they are to survive, elephants, lions or hippos need to generate an income for the people who live in the area. A tourism investor wishing to operate a lodge in a conservancy has to negotiate an agreement with the community concerned. For instance, the entrepreneur has to pay rent for the land that he builds his lodge on. Communities should also benefit from the lodge revenues. Moreover, local guides will accompany tourists on photo safaris, and lodge staff are recruited from surrounding villages and given training. Each tourist thus secures a number of jobs. All of a sudden, a live elephant is worth more to local families than its ivory.

Trust and dependence

The community decides what is done with the revenues from tourism such as land leases and profit-sharing. For example, in the Kabulabula Conservancy in the east of the Zambezi region (formerly Caprivi Strip) in Namibia, the additional income is used to finance a task force that intervenes when elephants come too close to maize fields, assisting in human-wildlife conflict situations. Hence, an economic activity is created, and a once desperately poor community experiences significant development gains. Success is based on trust, but also on dependence. Investors bring capital and expertise, both of which are lacking in the villages. Without the conservancy area and its wildlife management, the lodges could not be commercially viable.

The first five communal conservancies were established in Namibia in the early 1990s. Today, there are 82 of them. In 2012, they generated € 3.7 million in revenues, ensuring major benefits for local communities. Nature benefits as well. Lion, elephant and cheetah populations are recovering in Namibia.

The concept is to be extended to other KAZA countries. The first spin-off is already operating in Zambia, and more will follow. The WWF supports the communities in negotiations with investors and helps them to manage land and resources including the wildlife populations.

Another example of a conservation area with major tourist potential is the Virunga National Park, which straddles the borders of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Uganda. It is the oldest national park in Africa and one of the most biologically diverse places in the world. It contains rainforest, savannah and wetland habitats, offering spectacular landscapes that range from glaciers to active volcanoes. Virunga is famous for its mountain gorillas, which are found only at the intersection of the three countries. As long ago as the 1980s, ecotourism flourished here and provided the local people with an important source of income.

This setup provided an astonishingly effective protection of the natural resources even in the years of civil strife, which involved different rebel groups. For fear of unleashing international protest and in the hope of reaping profits from tourism, the dominant Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) largely preserved the national park and its gorillas.

Oil extraction averted for the moment

A much greater threat is currently presented by a number of European energy companies, which wish to drill for oil in the Virunga Park. Doing so would have devastating consequences. Due to strong WWF campaigning, the corporations agreed to abandon their plans. In 2014, the UK based company Soco became the last concession holder to withdraw from Virunga – for the time being. The WWF is now campaigning to persuade the DRC government not to award any more oil concessions in national parks as a matter of principle and to cancel the ones that have already been awarded.

Even without its oil, the park is an important economic asset. Around 4 million people live in the vicinity of the national park, and 50,000 of them earn a living directly from it, mostly as fishermen on Lake Edward. The true destiny of this park is to develop economic activity in harmony with nature conservation, with ecotourism playing a key role.

From 2012 to 2014, the DRC part of Virunga National Park was closed because of security issues. It reopened recently, though many tourists have been deterred by the clashes that still occur from time to time between government forces and armed militias. Once stability returns to the region, tourism can quickly become one of the most important income sources for the local people. Before the civil war, Virunga attracted more visitors than the legendary Serengeti in Kenya.

A study conducted on behalf of WWF has concluded that sensitive ecotourism could directly secure 7,000 jobs for rangers, guides and lodge service personnel; and more employment would be generated in related sectors. The general upswing could then drive the entire economy. Catering for holidaymakers could bring in more than $ 200 million for the local population. The Congolese would thus profit permanently from the exceptional natural wealth of this national park – without sacrificing it for the short-term profits of an oil boom.

Despite their marked differences, KAZA and Virunga both show ways in which sustainable development can be achieved. Tourism alone will not bring salvation but it can help to improve the prospects of local people in emerging and developing economies. Virunga and KAZA also send an important message to conservationists: wildlife and nature can only be protected with the support, not the opposition, of local communities. A live elephant needs to be worth more than a dead one.

Brit Reichelt-Zolho is programme officer for southern Africa for WWF Germany.

brit.reichelt-zolho@wwf.de

Johannes Kirchgatter is programme officer for central Africa for WWF Germany.

johannes.kirchgatter@wwf.de

Links:

Kavango-Zambezi Conservation Area (KAZA):

http://www.kavangozambezi.org/

Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo:

https://virunga.org/