Linguistic heritage

Tu di worl: Creole goes global

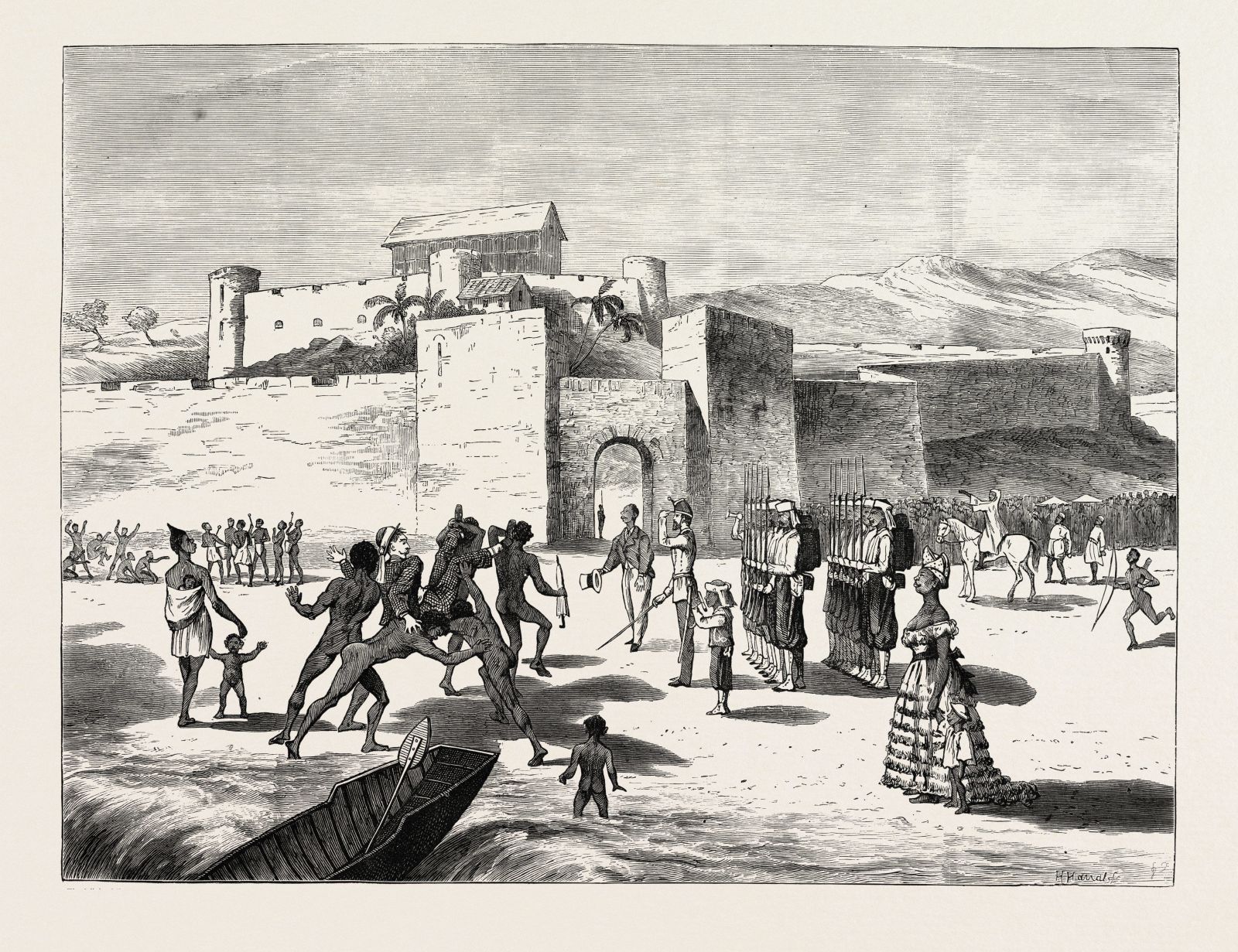

The modern world, as we know it, was formed on the islands and territories in the Caribbean Sea. It was here, rather than in Europe, that a large labour force was first used for the manufacture of a mass consumer product: sugar. By the mid 17th century, sugar plantations were large-scale agro-industrial operations.

The labour force, which can be described as a proto-proletariat, was made up of millions of enslaved Africans and some enslaved indigenous people. Enslavers of English, Dutch, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Danish origin were in control.

The sugar plantation colonies in and around the Caribbean were the pioneers of the European-based manufacturing operations which were at the heart of the industrial revolution. The Caribbean sugar plantations were, as suggested by historians C. L. R. James and Eric Williams, also the main sources of capital used to finance the industrial revolution in the “mother countries” in Europe.

New world, new languages

Within this new world, Africa, the Americas and Europe collided. The old identities – and with them, the languages that expressed them – died. Indigenous languages such as Kaliphuna, Guanahátabey and Ciguayo are no longer spoken. Colonial genocide erased their speakers in the 16th and 17th centuries. New languages emerged, now called Creoles. They were the result of colonial interaction between speakers of European and West African languages.

Typically, these languages’ vocabulary derived from a European language such as English, French or Spanish. The syntactic structures of these languages, however, are very similar. The French-vocabulary Creole (spoken in Martinique, Guadeloupe, St. Lucia and Dominica), the Spanish/Portuguese Creole (spoken in Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao) and the English-lexicon Creole (spoken in Jamaica, Antigua, St. Vincent and Guyana) share striking similarities in their grammar. This resemblance is probably rooted in the West African languages which the first generation of enslaved Africans spoke.

It is clear that the Creole languages of the Caribbean – and by extension the Atlantic area, including Guyana, French Guiana and Suriname in South America, Georgia and South Carolina in North America, Sierra Leone and Nigeria in West Africa – constitute a family of languages. They reflect a set of related identities and historical experiences, dating back to the time when the Caribbean was the centre of global economic development.

When European empires expanded into the Indian and Pacific Oceans in the 18th and 19th centuries, they used the Caribbean as a model for establishing plantation colonies. People and languages from the Caribbean and Atlantic were brought to new places. As a result, the Creole languages spoken in the Indian and Pacific Oceans have many features in common with those of the Atlantic.

Power and people

The international system is based on states organised around the sense of nation produced by the technologies of writing and print applied to national languages. This is a system which, up to the second decade of the 21st century, has been centred on the countries of northern Europe and North America. On the periphery are the formerly colonised countries of the so-called “developing world”, including the countries of the Caribbean.

For official purposes, these countries still use languages of the former colonial powers – but that is not the way most of their people speak. This is true for many ex-colonial countries in Africa, Asia and the Pacific. Marginalised linguistic, cultural and ethnic minorities in the countries of Europe and North America have to cope with similar circumstances.

In Jamaica, a cultural struggle has resulted in the largely unwritten Creole becoming the language that expresses an alternative, mass-based sense of national identity, within an official language framework dominated by English. This reverberates globally particularly through music. Leading Jamaican artists have become popular internationally (see box). One reason is certainly that the people in many other former colonies experience similar language tensions to those evident in Jamaica. Moreover, the marginalised linguistic, cultural and ethnic minorities in Europe and North America are all too familiar with this situation.

Against this background, on wings of song, albeit with some digital assistance, Jamaica has been able to globalise the bitter-sweet experience of a local language struggle. This is a fight to ensure that the national identity embodied by the state is the one that is associated with mass language of the descendants of African slaves – for example Jamaican Creole, rather than English, the language of the colonial elite. Jamaican Creole has gone global, proclaiming itself and its associated national identity “tu di worl”.

Hubert Devonish is professor of linguistics at the University of the West Indies. He is based at the University’s Mona campus in Kingston, Jamaica.

hubert.devonish@uwimona.edu.jm