China

How China is causing global shifts

Until the 1980s, China’s economy was based on agriculture and the small, centrally planned manufacturing sector. The turning point came with Deng Xiaoping’s policy of “reform and opening up”. It gradually introduced competition and private enterprise.

The Communist Party stopped issuing dictatorial commands from the capital. Moreover, it evaluated policy outcomes in the regions in a comparatively objective manner, using what worked well in one place as a blueprint for others. Market incentives increasingly took the place of the planning bureaucracy. The outlook of access to China’s huge domestic market made foreign investors make major concessions regarding the transfer of technology and expertise.

As the “world’s workshop”, China initially made simple industrial products for international customers. Today, it is itself a major R&D (research and development) player in the fields of artificial intelligence, biotechnology, information technology and electromobility. The latest Global Innovation Index ranks China 11th in the world, ahead of France, for example.

As the world’s second largest economy, China is now Germany’s most important trading partner. According to a recent study by the German Economic Institute (IW) – a think tank with close ties to business – it also dominates trade with the major countries of the so-called global south. It has overtaken the EU and the USA as their top trading partner.

Geostrategic influence

Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the world’s largest infrastructure initiative, China aspires to promote development in other countries.

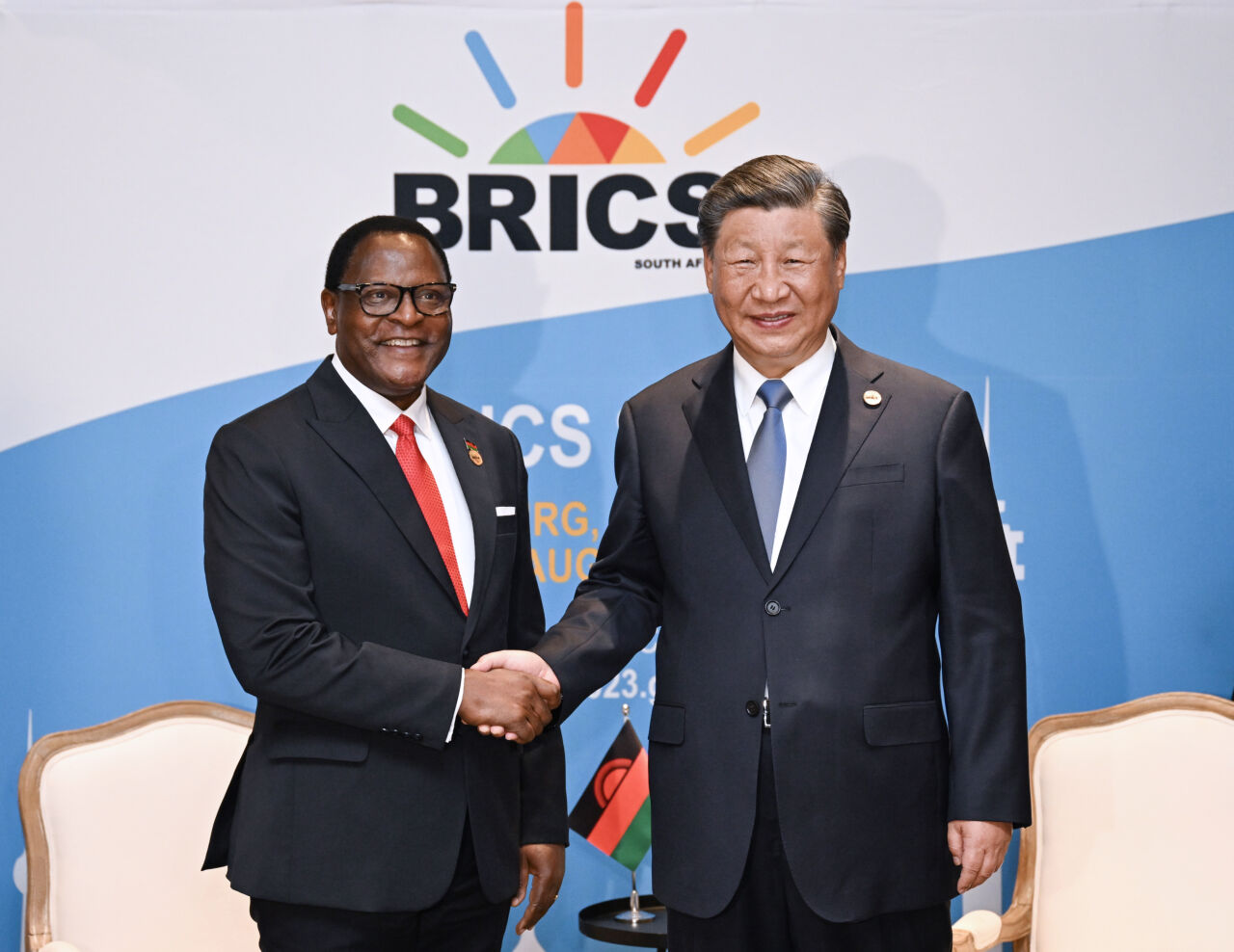

It is also using the BRICS group to expand its geostrategic influence. This alliance was originally forged by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa and has now become BRICS+, as more countries have joined. With the exception of India and Brazil, all of its members are also part of the BRI.

Antara Ghosal Singh of the Indian think tank Observer Research Foundation points out that the BRICS+ members play dominant roles in supranational regional organisations. She believes that China hopes the BRICS+ will allow it to exert influence on the African Union, the Arab League, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and Mercosur in South America.

The BRICS+ countries share a minimal consensus that suites Beijing’s wishes: an international world order that is less dominated by western advanced nations. This stance does not necessarily imply hostility towards the west. Most members probably see things the way India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar does. He said in September: “India is not anti-west but non-west”. BRICS+ decisions require unanimity, so China, Russia and Iran cannot easily impose their respective anti-western positions. In fact, most BRICS+ members probably wish to avoid radical polarisation.

This is so even though the western allies that belong to the BRICS+ barely implement western sanctions against Russia or Iran. The reason is that they see the sanctions as a threat. Punitive measures such as freezing foreign-exchange reserves or excluding banks from the international payment system SWIFT trigger their desire for alternatives to the US-dominated financial system. That is true even of countries that are close to the west. Creating a real alternative, however, is difficult and takes time. That said, it is noteworthy that payments for gas and oil shipments from the UAE to India and China are already settled in national currencies rather than the dollar.

The BRICS have even set up an international financial institution (IFI) of their own: the Shanghai-based New Development Bank (NDB). Thanks to the accession of wealthy Gulf States, the bank could increase its capital and then become able to play a greater role. It might become more competitive alongside other IFIs – without applying the conditions that typically go along with loans from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Low-income countries have not forgotten that established donor nations – just like China today – have always been partly motivated by a desire to access (and develop) markets. They also remember that austerity programmes in the wake of structural adjustment were often painful. China’s government is capitalising on the fact that established donors have lost faith among developing countries.

However, there is no way to know whether cooperation with Beijing will work out better in the long term. As a lender, the People’s Republic is generally opposed to forgiving loans in debt crises. Not all of the projects that got its supports prove sustainable. It causes further dissatisfaction that China mostly employs Chinese workers in projects and thus generates comparatively few jobs in partner countries.

At the same time, China obviously is facing serious economic problems domestically. Speculative failures in the real-estate sector, the ageing of society and highly indebted state-owned enterprises mean that it will not be easy to continue the success story of the last four decades. The way forward is unclear – and that applies to China’s international engagement too.

Matthias von Hein is a sinologist and journalist.

von.hein.media@gmail.com