Public finance

African countries at risk

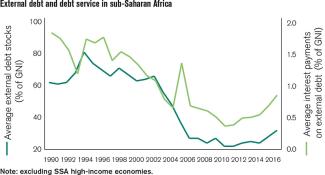

In the 1990s, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa saw debt ratios decline. The reasons were debt relief and economic growth. From the late 1990s on, the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) reduced low-income countries’ debt burdens. The idea was to free up resources for infrastructure investments and social spending, Mustapha and Prizzon write.

In the current decade, however, public debt and debt-service ratios have been rising again. According to the scholars, they are now higher than they were in 2006 when the MRDI started. Moreover, ratings by the World Bank and IMF suggest that low-income countries are now at high risk of debt distress, which occurs when a country struggles to service its debt.

The number of countries at risk in sub-Saharan Africa has more than doubled from eight countries in 2013 to 18 in 2018. Eight countries – Chad, Mozambique, Republic of the Congo, São Tomé and Principe, South Sudan, Sudan, The Gambia and Zimbabwe – are already in distress. According to the authors, borrowing is driven by the desire to mobilise resources for reaching global goals, implementing national development plans and turning low-income countries into middle-income ones.

The authors caution that even though borrowing is often seen as necessary for growth, unsustainable debt burdens may undermine progress. It is unhealthy that some governments are now pending more money on debt servicing than on their education or health sectors. High debt levels make them less able to attract investors and innovators.

Policymakers and practitioners need to pay more attention to the changing composition of debt and its accompanying risks, Mustapha and Prizzon demand. Three trends matter in particular:

- The share of multilateral and concessional debt has declined. For example, sub-Saharan multilateral debt has fallen from 53 % in 2005 to less than 40 % of the region’s external debt in 2016. One reason is that, as countries become middle-income countries, they are no longer eligible for multilateral and bilateral donors’ programmes.

- New bilateral sovereign creditors have increased their share in total public external debt from 15 % in 2007 to 30 % in 2016. For example, Chinese institutions are increasingly financing large-scale infrastructure projects in the region. These loans may lead to repayment problems if they do not generate sufficient returns.

- Sub-Saharan countries increasingly raise funds on international capital markets. They are thus exposed to risks regarding volatile exchange rates and interest rates. Investor interest may shift too.

The new finance landscape may render past debt-relief mechanisms obsolete and exposes countries to more financial risks (also note Jürgen Zattler in Focus section of D+C/E+Z e-Paper 2018/08). Both borrowers and lenders could do more to make debt more sustainable. The authors recommend reforms in three areas:

- building the capacity of borrowing countries to manage debt responsibly,

- enhancing transparency for all parties involved, and

- developing state-contingent debt instruments (SCDIs) which would link debt service to pre-defined macroeconomic variables, such as GDP growth: in the case of a downturn, the debt-service burden would thus be reduced automatically.

In many sub-Saharan countries, institutional capacity for effective debt management is weak. Shortcomings include the fragmentation of debt management responsibilities across several government entities, lack of political commitment, high staff turnover in debt management units as well as unreliable debt recording systems and data gaps, according to Mustapha and Prizzon. However, improving debt management is not a panacea and has to be supported by sound macroeconomic, fiscal and tax policies.

Lenders need to promote responsible lending too. The authors argue for improving transparency and information-sharing among creditors and borrowers. The World Bank and the IMF should reach out to emerging-market creditors for better coordination. New approaches such as SCDIs might also help.

Link

Mustapha, S., and Prizzon, A., 2018: Africa’s rising debt. How to avoid a new crisis.