Mali

It is hard to see how ECOWAS can escape stalemate

When military leaders seized power in Mali in August 2020, they promised elections for the country to return to constitutional rule. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) set the deadline of 27 February 2022. Mali belongs to this regional block.

Assimi Goïta, the army officer who staged the coup, did not like the deadline. Late last year, he insisted on a transition period that might last until 2026. Appointing himself president, he had reaffirmed his power grab in a second coup in May 2021.

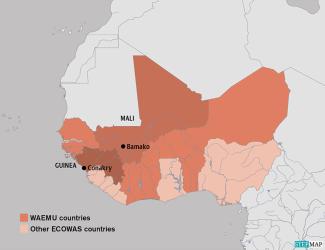

ECOWAS does not accept the election postponement, nor did the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) which uses the CFA Franc. All WAEMU members, including Mali, belong to ECOWAS as well.

On 9 January, the top leaders of ECOWAS and WEAMU met in Accra, the Ghanaian capital. The presidents of Nigeria and Togo, Muhammadu Buhari and Faure Gnassingbé, were absent. The military government of Guinea Conakry did not take part either. Because of its undemocratic nature, it has been suspended from intergovernmental meetings. Compared with other regional blocks in Africa, ECOWAS has a good, though not perfect history of insisting on constitutional governance (see Vladimir Antwi-Danso on www.dandc.eu).

To put pressure on Mali’s regime, the Accra summit imposed rather strict economic sanctions. Among other things, the list includes:

- the closure of member countries’ borders with Mali,

- the suspension of economic transactions (with exceptions for food, pharma and medical supplies), as well as

- the freezing of assets owned by the Malian state and its agencies.

The WAEMU added sanctions of its own.

Mali is an important country. It has a huge territory and shares borders with the geo-strategically important Algeria. What happens in Mali, can easily have impacts on all ECOWAS members.

Mali’s military junta responded in anger. Goïta called the sanctions “illegal, illegitimate and inhuman”. He asked his people to take to the streets to vent their anger. Thousands did so. Mali imposed reverse sanctions, moreover, claiming that both ECOWAS and WAEMU are manipulated by France and the EU.

Anti-French sentiments

Goïta’s regime is thus exploiting anti-French sentiments. Some journalists celebrate his stance as liberation from the dominance of the former colonial power. This kind of rhetoric resonates in many African countries.

The background of the current problems is Mali’s severe security crisis. When Libyan dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi was toppled in 2011, arms from his country suddenly became available. Since then, Islamist militias and other violent groups have been roaming Mali’s vast Saharan north. In 2012, Mali’s frustrated military grabbed power, but democracy was restored fast. Even with the support of French troops and a UN mission, however, the country’s security forces have not been able to stem unrest. Violence sometimes spills over into the more densely-populated south, and things have been deteriorating.

As the French public is unhappy with the situation, the French government wants to halve its military presence. In this setting, Mali’s current regime is said to be interested in support from Wagner Group, the private Russian military-service provider with a rather bad track record regarding human rights.

The other ECOWAS members, however, oppose Wagner involvement, and so do France and other European partners. Christine Lambrecht, Germany’s defence minister, has recently spoken out against the “deployment of mercenaries” for example. German soldiers take part in the UN mission. EU countries, moreover, are also keen on democratically legitimate rule.

The situation is tense. Humanitarian problems are getting worse in Mali. Other ECOWAS members are feeling the pinch too. Mali’s regime had a point, for example, when it stated that that Senegal’s main port normally has a lot of traffic thanks to landlocked Mali. The military government of Guinea Conakry, moreover, has said it will not enforce sanctions.

The good news is that leaders on all sides say they are still willing to talk. It is hard to see, however, how they might escape the current stalemate.

Karim Okanla is a media scholar and freelance author based in Benin.

karimokanla@yahoo.com