Fighting poverty

For all children to learn to read and write

The village teacher often does not show up. And when he does, he stands in front of the class and lectures some 50 children between the ages of five and 15. He tends to scream at farmers’ children who have trouble following the story he has chosen about the Underground in London or the Metro in Paris. The teacher, after all, is using a school book from the former colonial power, and it’s exotic content is one reason for him being stressed out. The children have learned to fear his outbursts of physical violence. Some long ago decided to follow his bad example and skip school altogether.

Of course, this scenario is a caricature of everyday life in a Third-World elementary school, but it is not totally unrealistic. As Carola Donner-Reichle, the InWEnt manager dealing with the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), puts it, “inadequate and outdated teaching material and methods” are still all too common. According to her, that is one of the main reasons for many children still not learning to read and write – mainly in Africa, but also in Asia and Latin America. “Enrolment statistics do not give us the whole picture”, she warns.

Rather, the children need to discuss situations in class that relate to their everyday life. Teaching methods should stimulate their curiosity, encouraging them to try things out and make their own little discoveries. Furthermore, teachers must deal with the children as individuals, finding out what they know already in order to form groups appropriately and enable them to act in a meaningful way. All this is taken for granted in Europe, but unfortunately still seems quite innovative in many poor regions of the world.

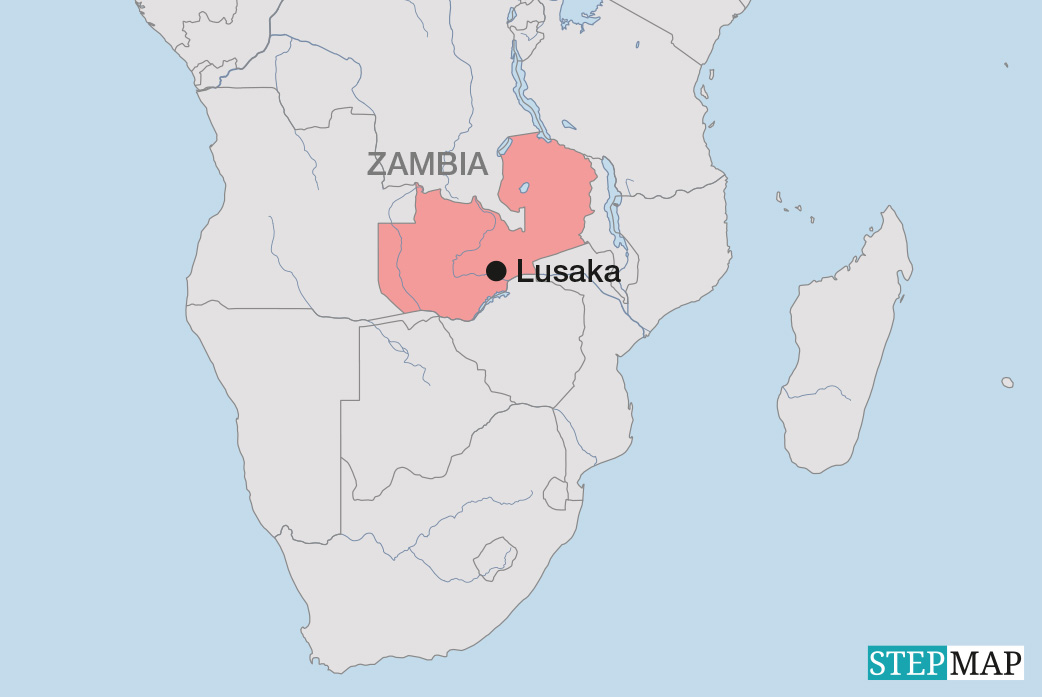

To improve matters, teachers have to be better qualified and motivated. InWEnt focuses on teacher educators' training, in cooperation with other agencies. “For example, we organise long-term capacity building programmes for educators at Teacher Training Colleges in Malawi,” the InWEnt manager reports. Such sequenced courses will gradually boost school performance. In Malawi, such these courses focus on the content, methods and principles of teaching language, mathematics and sciences. These are the areas the national government considers most urgent.

Reaching all branches

InWEnt systematically supports the policies designed by the partner countries. “There is no point in trying to force something upon them,” Donner-Reichle explains. In her view, long-term challenges must be addressed “at a systemic level”, as progress will only be sustainable if it is “driven by local forces” and affects “all relevant branches” of society. It is in this sense, that Germany’s Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development emphasises “country ownership”. As an implementing agenciy of the Ministry, InWEnt follows this policy.

Civil-society organisations generally demand more funds for official development assistance (ODA). However, they often do not address a problem that Donner-Reichle believes is crucial. While the head of InWEnt’s Social Development Department acknowledges that teachers are commonly under-paid and that higher salaries would provide incentives, she also stresses that such funding would have to be earmarked in national budgets and actually be disbursed by the authorities. Accordingly, she does not expect much change unless the respective ministries set the right priorities.

To raise awareness on budget issues, InWEnt organises capacity-building courses for top-level civil servants. Mozambique, Malawi and other southern African states are interested in improving the performance of their ministerial bureaucracies. “So far, officials from education ministries hardly ever spoke to those from the finance ministries,” Donner-Reichle explains. She considers it a big step forward that today they are not only doing so at the national level, but even across borders, exchanging experiences and good practices.

One thing civil servants must understand is that long-term success will depend on devolving powers from the capital cities. “Finance and human-resource decisions must be made at the level of districts, if local needs and conditions are to be taken account of adequately,” Donner-Reichler argues. Moreover, teachers have to be sensitised to issues of gender, ethnicity and religion. “It won’t do if teachers only give instructions from above when dealing with related tensions in school.”

InWEnt is therefore active in these areas too, organising conferences and offering various programmes in support of reform efforts. Donner-Reichle stresses the relevance of sharing information and experience across borders, including between developing countries themselves. InWEnt is not only providing key personnel with up-to-date knowledge and concepts, but also with an invaluable international network to follow and learn from international debate. Such exchange will contribute to making sure that village kids learn about goats, sheep and other animals they see every day, rather than having to worry about foreign systems of public transport. (dem)