Blog

Why I find the debate on an IP waiver awkward

This is actually a fight that the pharmaceuticals industry and the rich-nation governments that support them have already lost once. Quite likely, they will lose again. However, their surrender will not boost vaccine supply immediately, and not only because it will take some time before it happens.

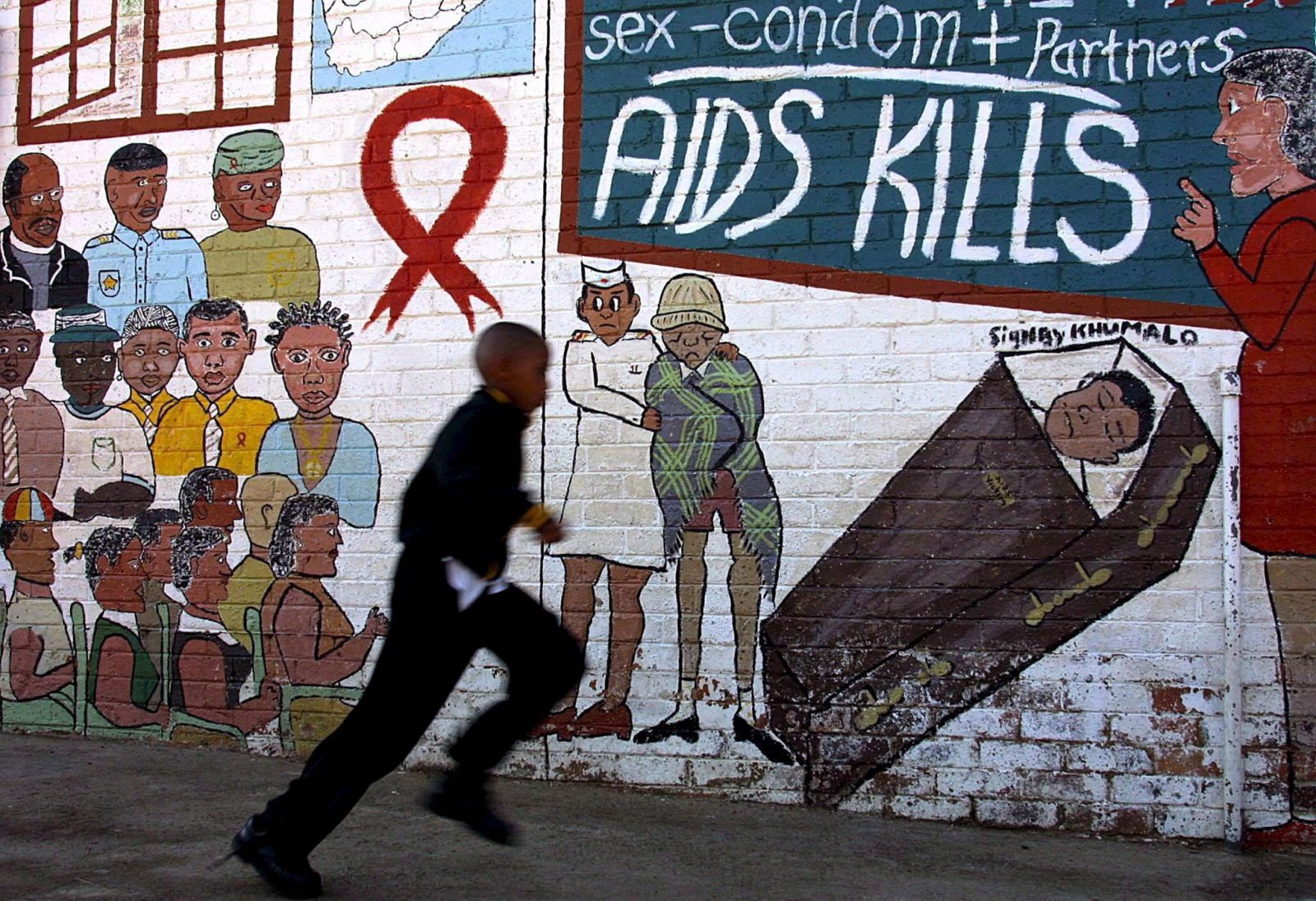

Current developments very much resemble what happened in the late 1990s, when innovative HIV/AIDS drugs saved lives in rich nations, but were unaffordable in developing countries. The stance that patents matter more than lives proved untenable. In 2001, therefore, the WTO (World Trade Organization) adopted a resolution according to which every nation has the right to grant compulsory licenses for the production of patent-protected drugs if and when that is necessary for safeguarding public health.

In WTO jargon, the related rules are called “flexibility”. They have had an impact even though they have hardly been implemented. Multinational corporations understood two things. Their bargaining position had become weaker, but they would keep their patents if they made the relevant drugs available at affordable prices in developing countries and emerging markets. Accordingly, prices for HIV/AIDS drugs fell without compulsory licensing.

What is different now

The scenario today is not exactly the same. At the turn of the millennium, the main problem in regard to HIV/AIDS medication was indeed high prices. Covid-19 vaccine shortages, by contrast, do not simply result from producers’ insistence on intellectual property rights. There are other bottlenecks, some of which are more important. The supply of ingredients is a problem, and production facilities need to be scaled up. Moreover, the technology used for some vaccines is new, so skilled specialists are rare.

It is very hard to argue, however, that the enforcement of the intellectual property regime somehow speeds up vaccine production. Indeed, some industry observers say that production capacity would be stronger today had the IP waiver that is being discussed now been granted six months ago.

My hunch is that the pressure on those who, like Germany’s Federal Government, still insist on IP rights will keep increasing. As was the case 20 years ago, the stance that patents matter more than human lives looks most unlikely to prevail. That patents are not currently the main problem will probably not matter much.

What matters is that they are conceivably part of the problem, and that is what international debate is focusing on. To some extent, governments are emphasising it to divert attention from failures. The USA has – for valid reasons – been accused of hoarding vaccines.

Making Biden look generous

In this context, the US administration’s declaration in favour of an IP waiver is smart diplomacy. It makes US President Joe Biden look generous. On the other hand, he is an experienced policymaker and probably remembers how the HIV/AIDS debate played out 20 years ago.

By contrast, the EU has exported some 200 million vaccine doses. To some extent, policymakers from European countries are thus less exposed to criticism. The full truth, nonetheless, is that vaccinations campaigns are now fast gaining momentum in Europe, but not in the developing countries and emerging markets that are currently harder hit by the pandemic. Unless EU leaders come up with a plan to ramp up vaccine supply around the world fast, the pressure to waive property rights will keep growing. The USA and the EU have a long history of insisting on IP rights and had a habit of putting pressure on African, Asian and Latin American governments so flexibility would not be made use of. They did their best to discourage other WTO members from exercising those rights. To some extent, a victory won in 2001 did not improve pharma supply as much as it could have because governments did not stand up to US and EU pressure.

India and South Africa could have done much more

In this context, it is odd that India and South Africa made the proposal to waive intellectual property in October, but they did not support it with any kind of assertive public diplomacy. They did not do much to either engage global media or involve international civil society, even though they surely know that both were essential in the past IP struggle 20 years ago. My hunch is that there are two main reasons:

- The Indian government generally resents the influence of global media and international civil society. After all, neither support its Hindu-supremacist agenda.

- In 2001, South Africa was on the wrong side of history. Then President Thabo Mbeki was in science denial, and civil-society campaigners were agitating against him too.

In any case, the top leaders in India and South Africa certainly did not prioritise this issue. Apparently, it did not seem urgent to them.

It is noteworthy, moreover, that China’s position in the waiver debate is ambiguous. There has been praise for Biden’s generosity, but Beijing’s main message seems to be that donating and selling vaccines to other countries is the real solution. The full truth is that China is currently scoring diplomatic points by supplying vaccines to other countries, for example in Latin America. Unlike some EU leaders, however, China does not seem eager to block the IP waiver.

It is sometimes argued that an IP waiver would benefit China most of all because it would give Chinese companies access to technology they do not have so far. I don’t think this argument makes much sense. To get a patent, an inventor must elaborate the technology. By definition, a patent means disclosing the most important secrets. That knowledge in itself, however, is normally not enough to use a technology. But it is the information competent scientists and engineers need to figure out how to do so. Moreover, the proposed waiver would be temporary, so IP protection would apply again once the pandemic is over.

Half-hearted approach

The joint initiative of India and South Africa looked a bit half-hearted right from the start. Had the two governments insisted on WTO flexibility to produce vaccines in October, we would not be having the global debate only months after they made the proposal.

I am not sure they would be producing the vaccines already. Scientists and engineers of Indian and South African pharma producers might still be figuring out how to use the patents. At the same time, they would’ve asserted the rights won in the WTO context 10 years ago, and I have no doubt that they would’ve found strong support from global media, international civil society as well as the governments of other developing countries and emerging markets.

Small least developed countries cannot be expected to stand up to the most powerful nations on their own. But the leading emerging markets are in a much stronger position. And they can easily team up with likeminded partners.

Hans Dembowski is the editor in chief of D+C/E+Z

euz.editor@dandc.eu