Multilateral affairs

IMF executive board re-endorses Georgieva

Georgieva is accused of manipulating information that international investors pay attention to. According to an expert report prepared by a law firm, she put pressure on the World Bank team preparing the Ease of Doing Business Report 2018. That pressure is said to have resulted in China rising a few notches in the Doing-Business Ranking from the 85th slot to the 78th slot. At the time, Georgieva was the World Bank’s chief executive.

Quite obviously, the leadership of an institution that claims to be a “ knowledge bank” must not interfere in its experts’ assessments. The top management should not have a say in the methodology used to compile an index. Manipulations of that kind do indeed undermine faith in institutions concerned.

Some observers, however, pretend that Georgieva caused serious harm to investors. They claim that the Doing Business index often guides large-scale investment decisions. This argument is entirely overblown. Whenever countries are similar, the ranking probably matters. If someone isn’t sure, for example, whether to set up a production site in Malawi or Zambia, the countries’ ranks in the index may indeed make the difference.

China, however, differs dramatically from every other country. In terms of population size, only India comes close. China’s economy, however, is much bigger – the second biggest after the USA. The domestic market is huge. China is under authoritarian rule, but unlike most dictatorships, the Communist regime managed to achieve fast economic growth for decades. Unlike many developing countries and emerging markets, moreover, China does not rely on the language of the former colonial power for official purposes. China is special in so many ways that anyone who wants to invest there will not take into account whether it ranks in the mid-80s or low-70s on some global index or another.

No precise yardstick

It is worth pointing out, moreover, that the methodology used to compile an index normally changes over the years. Though experts who design an index pretend to be offering something like an unequivocal yardstick that delivers precise results, their work is actually quite messy. How easy it is to do business somewhere, for instance, depends on many things. Three of the issues included in the Doing Business index are:

- how long it takes to register a new company,

- how long it takes to get a building permit, and

- how long it takes to file taxes.

All three things obviously matter. It is not at all clear, however, which aspect is the most important. Anyone who publishes this kind of an annual index needs to consider these things. Should all issues be considered to be of equal relevance? Should some of them be prioritised over others? What formula serves to aggregate many different criteria resulting in a single number per country?

When the Doing Business series was started after the turn of the millennium, the ease of firing staff was included in the index calculation. That decision was quite controversial. What is good for an individual employer, after all, is not necessarily good for an entire sector and even less for society in general. How labour regulations should figure the index became disputed, and after some years, labour regulations were dropped from the calculation. If labour relations are not considered, however, an important aspect of running a company slips off the radar.

The full truth is that indices are useful for understanding some general trends. The rankings of individual countries, however, should always be taken with a pinch of salt. They do not reflect any kind of objective truth, but result from human judgment.

A series ends

The World Bank has recently decided it will discontinue the Doing Business series. The reputational damage is too big to be repaired. Indeed, the manipulation that Georgieva was allegedly involved in was only one of several such cases – and quite clearly a minor one. In the past, a former chief economist of the World Bank felt compelled to apologise to Chile, admitting that the country’s ranking had been kept lower than deserved during the presidency of Michelle Bachelet, a socialist. It is noteworthy, moreover, that China rose much faster in the ranking after Georgieva left the World Bank and moved on to the IMF. Last year, China was in the 31st place.

For good reason, the executive board of the IMF has decided to keep Georgieva as managing director. She has been doing excellent work in regard to Covid-19 and the climate crisis, for example. Among other things, she helped to bring about the recent expansion of special drawing rights, boosting developing countries' financial firepower. Governments of low- and middle-income countries appreciate her efforts. It probably helps that she is the first person from a developing country – Bulgaria, an upper middle-income country – to lead the IMF.

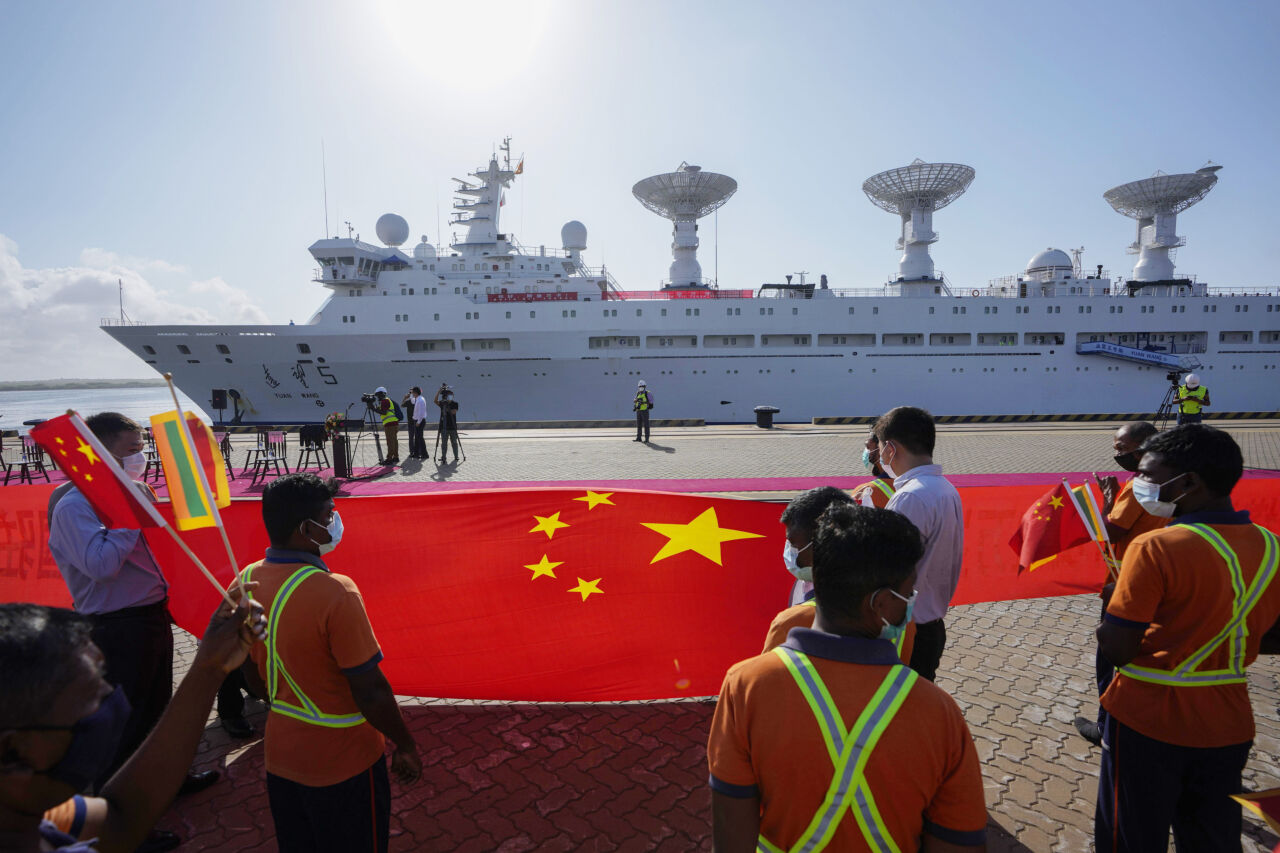

To a large extent, the debate about whether she should stay or not resulted from the growing tensions between the USA and China. Critics accused her of favouring the People’s Republic and not just of manipulating the index. Especially the governments of the USA and Japan were uncomfortable with her, while European governments ultimately sided with China and Russia in support of her. Should further evidence emerge of her involvement in wrongdoing at the World Bank, the debate will be rekindled. US officials have stated they will be paying close attention. No doubt, the controversy has weakened Georgieva. The larger picture, however, is that the growing tensions between Washington and Beijing are weakening the IMF and multilateral institutions in general.

Hans Dembowski is editor in chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu

Update, Wednesday 13 October 2021, 10:15 Frankfurt time: I have changed the final two paragraphs, adding the sentence about speical drawing rights, including the link to our comment, as well as two sentences on the US position.