Literature

Finding a nation’s voice

In an article in the magazine New African, Namibia was recently referred to as “Africa’s non-African country”. The article stated: “Power cuts are unknown, the roads are good, the water supply works, traffic jams are almost non-existent …”

While the article painted Namibia in a brilliant light, the painting was rather incomplete. The above-mentioned things are only true in some parts of the country. Elsewhere, there are plenty power cuts and Central Namibia is currently suffering a water crisis.

I love being African, so having my country referred to as “non-African” does not sit too well with me, maybe because the article seemed to equate “African” with being disorganised and underdeveloped. But while some African countries may be weak in infrastructure, they have other strong points.

For instance: when it comes to literature, it seems that Namibia is Africa’s unloved step-child. Why is so little known and said about Namibian literature? Mostly, because Namibian literature is still evolving. A lot of poetry, drama and autobiographical writing has been published, but not much fiction. All of the literature is in English, by the way.

In the past, there have been works by Namibian writers in other languages, for instance in Afrikaans, German, Otjiherero, Damara/Nama and some San languages. Namibian literature before independence was really more an extension of the South African or German literary scene. After independence, at least initially, there was a movement to publish “Namibian” books and create a true “Namibian literature”. That impetus has since eased off a bit.

In any case, Namibian writing often seems to take its cues from literary movements elsewhere, like postcolonial literature in Nigeria or Kenya. Afrofuturism is also becoming increasingly popular.

We have a long way to go before Namibians will have a presence in African literature. Namibian writing first needs to become popular in Namibia before we can expect it to be popular in the rest of the continent. There should be concerted effort on part of the Ministry of Education to promote local writers. Unfortunately, the people who serve on curriculum committees are themselves ignorant of literature in general and Namibian literature in particular.

We need serious attempts to capture our oral traditions in written forms. Furthermore, we should use electronic resources like YouTube to bring poetry and drama to those who would otherwise not be interested in it. Namibian authors like Lydia Shaketange, Ellen Ndeshi Namhila or Jane Katjavivi, but also the new generation of contemporary writers like the bloggers Hugh Ellis and Martha Mukaiwa should be on Africa’s – and the world’s – reading list.

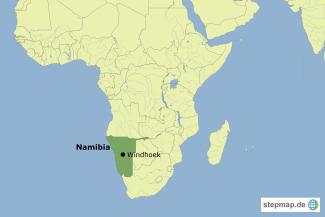

Munukayumbwa Mwiya is a writer and lives in Windhoek, Namibia.